- Characteristics of Waxy Oil from Waste High-Density Polyethylene via In-Situ Catalytic Pyrolysis

Joo-Hyeong Yoon

, Jong-Su Kim, Hyeong-Jin Kim, and Soo-Hwa Jeong†

, Jong-Su Kim, Hyeong-Jin Kim, and Soo-Hwa Jeong†

Korea Institute of Industrial Technology (KITECH), 89 Yangdaegiro-gil, Ipjang-myeon, Seobuk-gu, Cheonan-si 31056, Korea

- In-situ 방식 촉매 열분해를 통한 폐 HDPE으로부터의 Waxy Oil의 특성 연구

한국생산기술연구원 저탄소배출제어부문

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

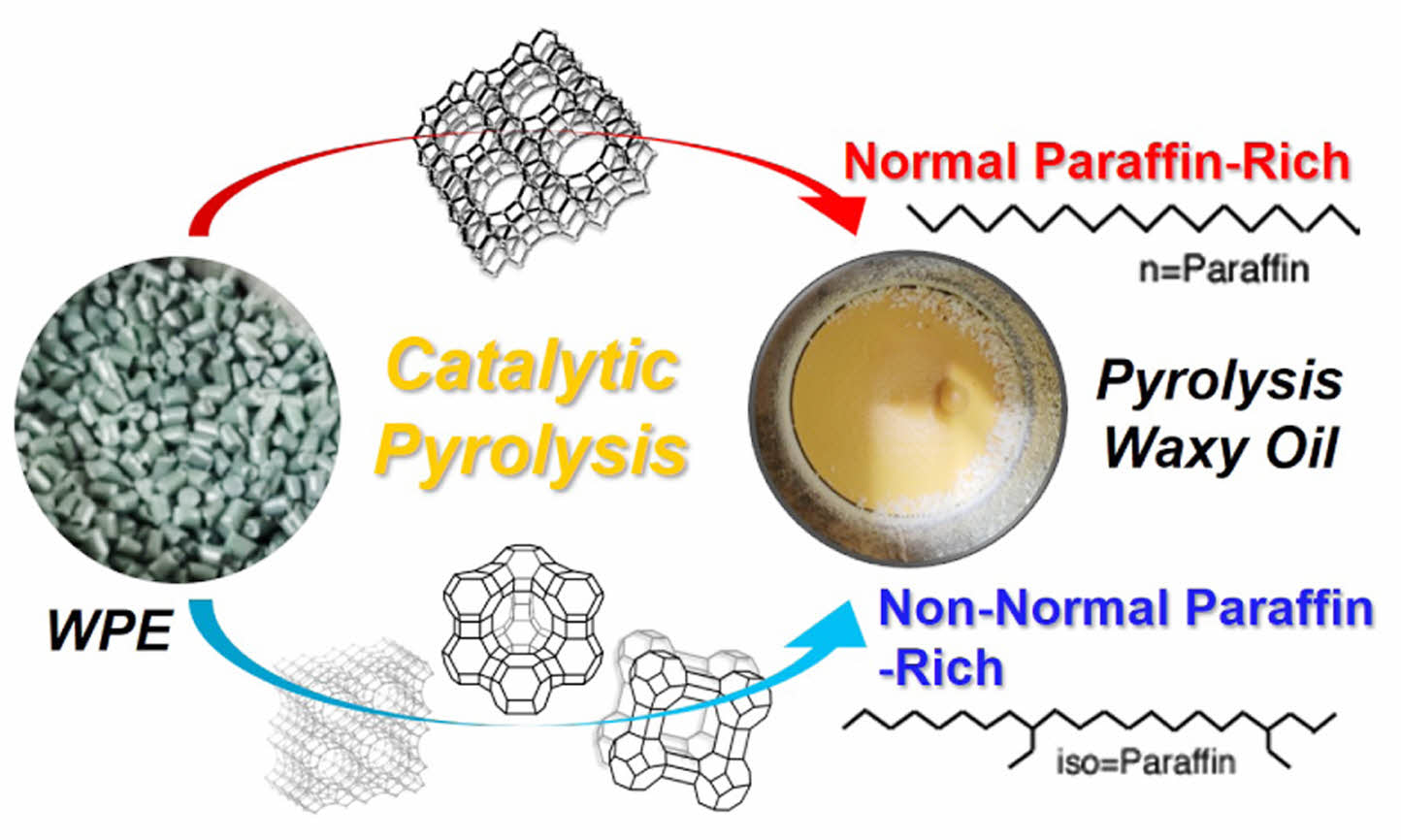

The primary objective of this research is to compare the characteristics of waxy oil obtained from the pyrolysis of waste polyethylene. Four different zeolite-based catalysts were used to compare the characteristics of waxy oil. This study focused on the effects of reaction temperature, gas flow rate, and zeolite type on the yield and composition of waxy oil. The results showed that the maximum yield of recovered waxy oil was approximately 71.1 wt% at 460 ℃ under non-catalytic conditions. When the A4 zeolite was applied, the yield of waxy oil reached up to 76.5 wt%. In contrast, when a ZSM-5 catalyst was used for pyrolysis, the recovered waxy oil was converted into gas, reaching up to approximately 84.1 wt%. The pyrolysis oil from waste PE was characterized using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. High acidity catalysts such as Beta, Y zeolite, and ZSM-5 produced 22-71.9% aromatic hydrocarbons. In contrast, the low-acidity A4 zeolite yielded non-aromatic hydrocarbons, maximizing the production of oxygenated hydrocarbons (26%) such as alcohols. Simulated distillation (SIMDIS) analysis showed that A4 zeolite generated the maximum wax content with a boiling point above 370 ℃ and 92% non-normal paraffin (iso- and cyclo-structured). The results of this experiment prove that using A4 zeolite, the waxy oil primarily consists of branched paraffins, making it a promising resource for lubricant production and chemical platform applications.

본 연구의 주요 목적은 폐 폴리에틸렌의 열분해로부터 얻은 왁스 오일의 특성을 비교하는 것이다. 특성이 다른 네 종류의 제올라이트를 사용하여 왁스 및 오일의 특성을 비교했다. 본 연구는 반응 온도, 가스 유량 그리고 제올라이트 유형이 왁스 및 오일의 수율과 조성에 미치는 영향에 초점을 맞추었다. 회수된 왁스 및 오일의 최대 수율이 비 촉매 조건에서 460 ℃에서 약 71.1 wt%였다. A4 제올라이트를 적용하였을 때, 왁스 및 오일은 약 76.5 wt%의 최대 수율 보였다. 반면, ZSM-5 촉매를 열분해에 사용했을 때, 회수된 왁스 및 오일은 약 84.1 wt%로 전환되었다. 폐 PE의 열분해 오일은 gas chromatography-mass spectrometry(GC-MS) 분석을 사용하여 특성을 비교하였다. Beta, Y zeolite 그리고 ZSM-5와 같은 고 산점 촉매는 22-71.9%의 방향족 탄화수소를 생산되었다. 반면, 저 산점의 A4 zeolite는 비 방향족 탄화수소를 생산하여 알코올과 같은 산소화된 탄화수소(26%)의 생산을 극대화했다. Simulated distillation(SIMDIS) 분석 결과에서 A4 zeolite 사용했을 때, non-normal paraffin(-iso 및 -cyclo 구조)이 92%로 크게 전환되었다. 따라서 폐 PE 열분해 시, A4 zeolite를 사용하면 열분해 왁스는 주로 non-normal paraffin으로 구성되어 윤활제 생산 및 화학 플랫폼 응용 분야에 유망한 자원임을 판단된다.

The waxy oil was recovered from the pyrolysis of waste high density polyethylene (HDPE) using a fixed-bed reactor system. Non-acidic A4 zeolite achieved the highest yield of waxy oil (76.5 wt%) and medium wax (C24-C34). Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis revealed aromatic-free hydrocarbons with A4 zeolite and high aromatic content with Beta, Y, and ZSM-5 zeolites. Simulated distillation (SIMDIS) analysis showed A4 zeolite produced 92% non-normal paraffins, with branched structures ideal for lubricant production. Zeolite catalysts significantly influenced the selectivity and efficiency of pyrolysis products, offering potential for chemical platform applications.

Keywords: plastic waste, pyrolysis, polyethylene, waxy oil, zeolite, paraffin.

This work was supported by 1) Korea Environmental Industry and Technology Institute (KEITI) through Center of plasma process for organic material recycling Project, funded by Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (No.2022003650002). 2) Korea Environmental Industry, Technology Institute (KEITI) and the Ministry Environment of Republic of Korea (No. 2021003350010).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Detailed information on the mass balance of pyrolysis products (including calculation formulas) and the effect of A4 zeolite calcination during catalytic pyrolysis is available in the Supporting Information at http://journal.polymer-korea.or.kr.

PK_2025_049_05_579_Supporting_Information.pdf (300 kb)

Supplementary Information

For several decades, the increasing global production of waste plastics has become a critical environmental concern, primarily due to the carbon pollutants emitted during decomposition.1 The annual accumulation of polyethylene (PE) has reached unprecedented levels, leading to numerous environmental concerns.2 Low-density PE, high-density PE, and polypropylene (PP) are the most important polymers, accounting for over 80% of global polymer demand.3 PE is the most widely produced polymer after PP, significantly contributing to substantial amounts of waste.

Incineration and landfilling, the conventional means of plastic disposal, fail to mitigate these problems effectively and instead contribute to the release of harmful pollutants and greenhouse gases such as CO2.4 In response to these challenges, pyrolysis has gained significant interest as an alternative disposal method for waste plastic. It offers numerous advantages, including the potential to reduce CO2 emissions and improve economics.5 Pyrolysis of waste plastics produces char, oil, and gas, which can be used to convert energy into many fields. It offers a promising solution by converting plastic waste into valuable products while minimizing the generation of CO2.6 The transition towards pyrolysis-based waste treatment aligns with emerging environmental policies to reduce carbon footprints and promote sustainable waste management practices.7 A comprehensive review of existing literature on plastic waste management policies and the environmental impacts of various disposal methods provides information on pyrolysis.8

The pyrolysis process is a chemical process that converts polymers into monomers or oligomers by applying heat under oxygen-free conditions. The reaction conditions vary depending on the characteristics of the sample. Representative examples include batch-type fixed bed reactors, continuous fluidized bed reactors, and conical spouted reactors. To commercialize the processing of these waste plastics, there must be a continuous feed supply. Therefore, fluidized bed or conical spouted bed reactors can provide continuous feeding.9 These reactors facilitate rapid pyrolysis. This enables higher recovery of valuable products such as olefins and oils from polyolefins.10 At temperatures between 430 and 550 ℃, polyolefins produce mainly wax products, while higher temperatures around 700℃ increase the production of gases and oils. These include high yields of olefins and aromatics. For example, pyrolysis at 700–750℃ in a fluidized bed produces significant amounts of olefins.11 This is very similar to the results of the naphtha cracking process.12 Tran et al. studied the catalytic cracking of waste plastic pyrolysis oil in a fluidized bed reactor. They demonstrated improved recovery of light olefins and oils, which are valuable hydrocarbons for industrial applications.13 This approach is suitable for recycling mixed polyolefin wastes on an industrial scale, as it allows the recovery of valuable hydrocarbons. The pyrolysis techniques offer a viable approach to managing the waste stream, specifically focusing on wax and fuel oil production. The wax markets are rapidly growing, with projections indicating over 70% expansion in 2023.14-16 The wax recovered from pyrolysis has various industrial applications, such as coatings, lubricants, and cosmetics.11,17 Moreover, these products show potential for high-value chemical syntheses using additional catalysts and thermal cracking processes. The PE and PP are typically used for plastic pyrolysis, with PE yielding more wax than PP.11 The potential economic and environmental benefits of pyrolysis as a viable approach to PE waste management are further highlighted by exploring the growing wax market and its various applications.18-24 Oil extraction from plastic waste pyrolysis has been studied extensively. PE derivatives primarily yield waxy substances. Research has focused on the thermal and catalytic pyrolysis of PE materials, investigating wax formation during the pyrolysis of waste PE. Maniscalco et al. observed pyrolysis at lower heating rates in the 420–450 ℃ temperature range and achieved waxy-oil optimum yields of 42–54.5 wt%.23 Al-Salem et al. obtained wax from the pyrolysis of both virgin and recycled PE in a reactor at 600 ℃, with a maximum wax yield of 43.7 wt%.24 Saeaung et al. performed the catalytic pyrolysis of petroleum-based and biodegradable plastic wastes to obtain high-value chemicals, processing high-density and low-density PE.25 They investigated the effect of pyrolysis temperatures (400–600 ℃) and catalysts (zeolite, spent FCC, and MgO) on the yield and composition of the waxy oils, determining that the main components of these liquids were alkenes, alkanes, and aromatics. The use of spent FCC catalysts resulted in a significant decrease in wax production and increased hydrocarbons and aromatics in the gasoline range. Kremer et al. performed catalytic pyrolysis on a mixture of mechanically non-recyclable waste plastics in a fixed bed reactor at 475 ℃, achieving an optimum yield of 55 wt%, with the oil and wax fraction contributing 23 and 27 wt%, respectively, using an FCC catalyst.26 Wang et al. performed catalytic pyrolysis experiments on PE to produce monocyclic aromatics selectively.27 Furthermore, the recovered liquid had high monocyclic aromatic concentrations with BTX compounds. So far, most studies on catalytic pyrolysis have focused on the wax cracking.

More recently, there have been studies to pyrolyze waste plastics to utilize wax as a potential resource. Neuner et al. studied the conversion of Fischer–Tropsch waxes and plastic waste pyrolysis condensate into lubricating oils and potential steam cracker feedstocks, finding that lubricants from plastic waste exhibit lower cloud points and higher temperature stability.28 The research demonstrates the potential for recycling plastic waste into high-quality lubricating oils. Among these wax applications, the utilization of lubricants has recently gained attention. Paraffinic waxes are used in the production of lubricants, and the more branched olefin waxes, the better. It should also be aromatics-free, as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are generally more reactive than saturated hydrocarbons.29 This high reactivity causes undesirable chemical reactions within the lubricant, which shortens its life span. Using aromatic-free waxes in lubricant formulations can improve stability and performance.30 Additionally, using aromatic-based wax dissolvers is hazardous and expensive to operate. Using waxes without aromatic compounds solves these problems and provides a safer and more cost-effective alternative.31 The lubricant industry can improve product stability and performance by utilizing aromatics-free waxes while meeting economic and environmental goals.

This study investigated the optimum yield of waxy oil derived from pyrolysis of waste PE fractions by varying the reaction temperature. In particular, zeolites with various Si/Al ratios as catalysts were compared to waxy oil paraffin. The trend of normal paraffin (linear) and non-normal paraffin (non-linear) contents was identified by simulated distillation (SIMDIS) analysis. In addition, we compared the trend by classifying the hydrocarbon distribution and grouping of pyrolysis oil using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis.

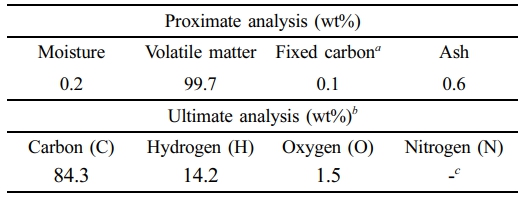

Feed Material. The waste PE fraction was used as the feedstock in the experiment. Pellet-type waste plastic with a diameter of 6 mm was obtained from Shoko Korea Co., Ltd. (South Korea). The proximate and ultimate analyses were performed on the waste PE, revealing a high content of volatile matter. The ultimate analysis consisted primarily of carbon and hydrogen (Table 1).

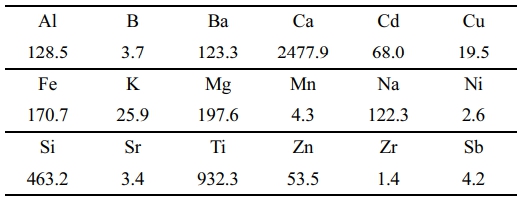

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was used to assess the inorganic content of the waste PE, with the results shown in Table 2. Notably, calcium, an alkali metal, had the highest concentration, followed by titanium. Trace metals were present in the original plastic samples.32 The silica (Si) exhibited a relatively low concentration, with trace amounts of various alkali metals.

Table 2 presents the ICP-MS analysis of waste PE, identifying trace metals that may influence pyrolysis performance. Previous studies have reported that specific metal components, such as Al, Fe, Ni, and Cu, exhibit catalytic effects during pyrolysis, promoting hydrocarbon decomposition and influencing product yields.33,34 Additionally, alkali and alkaline earth metals (e.g., Ca, K, Na) can alter pyrolysis stability and efficiency,35 while elements like Cd and Sb are associated with environmental and health concerns.36 In particular, Ca contained in the waste PE fraction used is the highest at 2477.9 ppm. It is thought that this will reduce the formation of char.

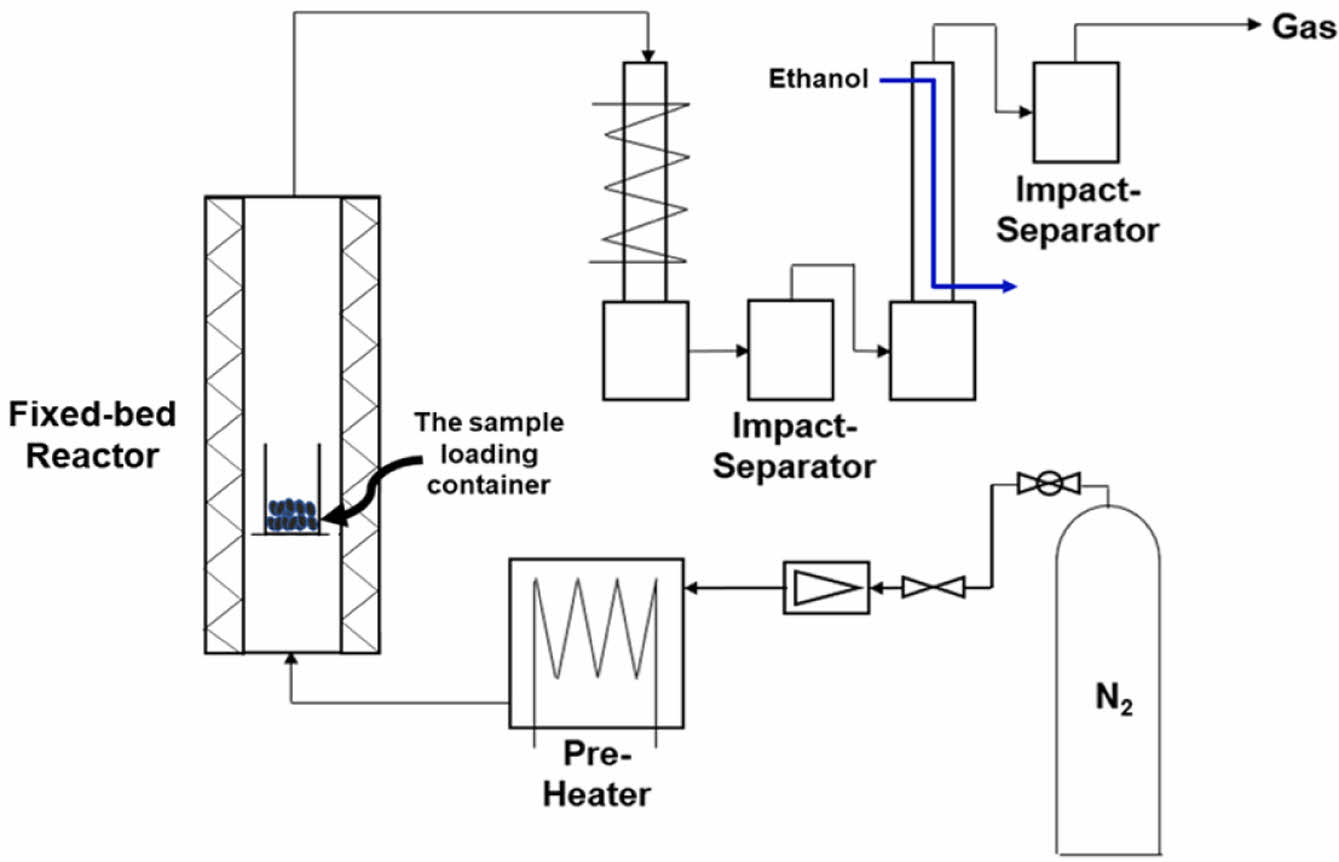

Experimental Setup. The pyrolysis experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of crucial reaction conditions (reaction temperature and nitrogen gas flow rate). The input amount of each experimental material was 200 g. A diagram of the lab-scale pyrolysis plant is presented in Figure 1. It consisted of a heating system and a quenching system. The heating system consisted of a pre-heater and a fixed-bed reactor. The pre-heater was used to compensate for the uneven temperature distribution of the fixed-bed reactor. The temperature was set to 800 ℃ to prevent a decrease in the temperature of the reactor due to cold nitrogen gas. The fixed-bed reactor, which was heated indirectly by electricity, was made of a 316SS tube with an inner diameter of 110 mm and a height of 650 mm. The thermocouples were positioned at the top, middle, and bottom of the reactor, and are aligned along the centerline of the reactor interior. The pyrolysis reaction temperature was calculated using the average values obtained from thermocouples in the reactor. Efficient recovery of the waxy oil was provided by a quenching system comprising a condenser wrapped with a heating band, an ethanol-cooled condenser, and two impact separators. The upper tube on the condenser wrapped with a heating band was maintained at 250 ℃. This is to prevent the wax components from condensing and clogging in the upper tube section of the condenser. Pyrolysis wax was primarily collected in the hopper of the first condenser. Additionally, relatively lighter wax fractions were captured in the first impact separator, and a small amount of oil-like product was collected in the hopper of the second condenser.

The ethanol-cooled condenser was maintained at -8 ℃ to capture the low-viscosity liquid not collected in the first condenser. The impact separators were applied to collect the compounds with higher and lower viscosity. During the pyrolysis experiment, excess gas generated from the pyrolysis reaction was burned in a flare stack.

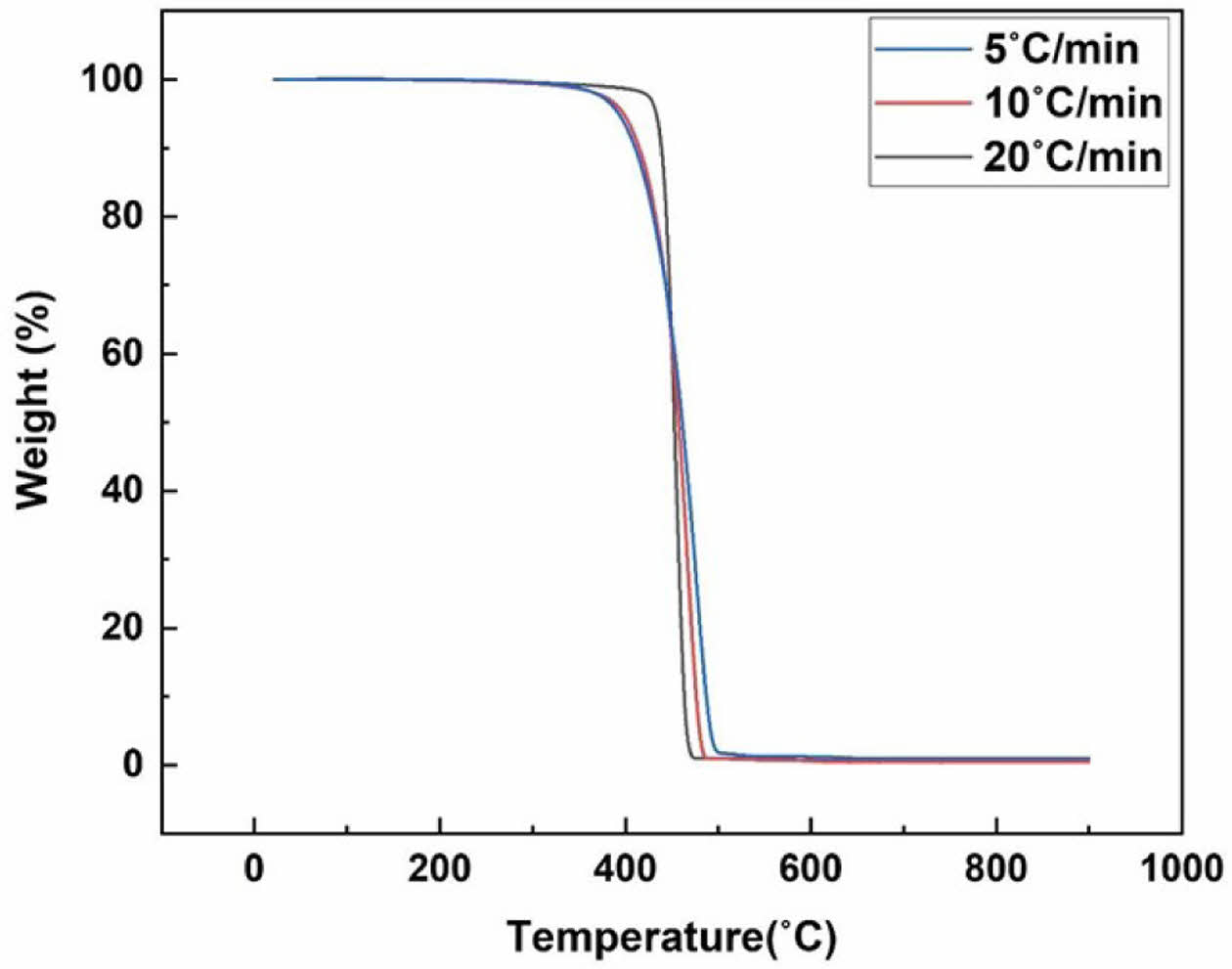

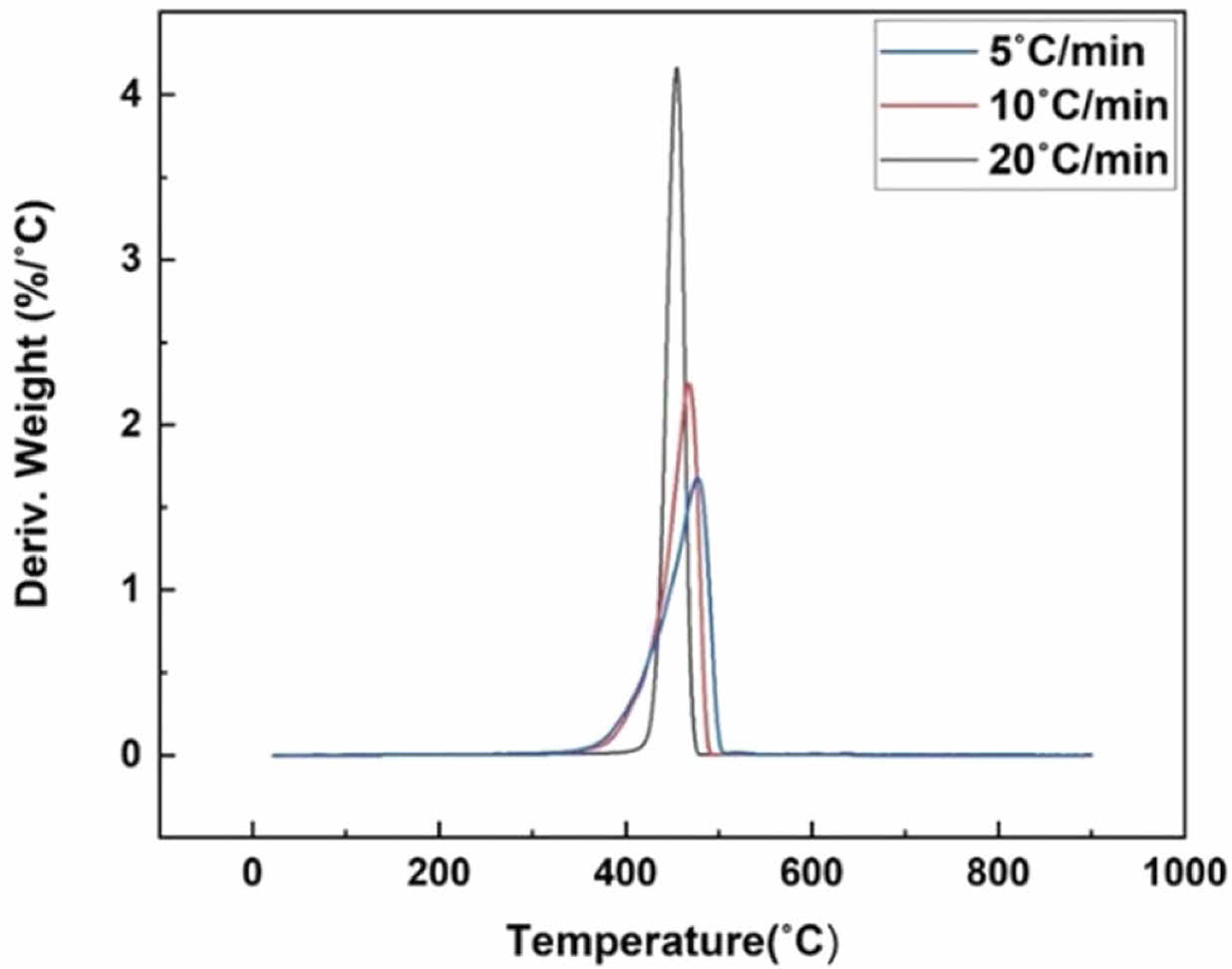

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA). Prior to the pyrolysis experiments, TGA was conducted on the waste PE fraction in a nitrogen atmosphere using a TG analyzer (TGA 4000, Perkin-Elmer). The experiments were conducted within a temperature range of up to 800 ℃ at 5, 10, and 20 ℃/min heating rates. The sample was 10-20 mg, and the nitrogen gas flow rate was 100 mL/min.

The thermogravimetric (TG) and differential thermogravimetry (DTG) curves of the waste PE fractions are shown in Figures 2 and 3. The results of the TGA of the waste PE fraction show that waste PE was completely decomposed. The TG curves of the waste PE fraction at heating rates of 5, 10, and 20 ℃/min indicate that it was completely decomposed at 480 and 500 ℃. Therefore, the waste PE tended to decompose at around 500 ℃. The TG curves at 5 and 10 ℃/min started degradation below 400 ℃, while the TG curve at 20 ℃/min exhibited degradation beginning above 400 ℃.

Also, the DTG curve at 20 ℃/min has the highest degradation rate, with the highest peak at 4 wt%/℃. The DTG curves show that the primary decomposition occurred within the 400-500 ℃ range for waste PE fraction. The DTG curve showed that the decomposition and pyrolysis activation temperature range became narrower as the heating rate increased.

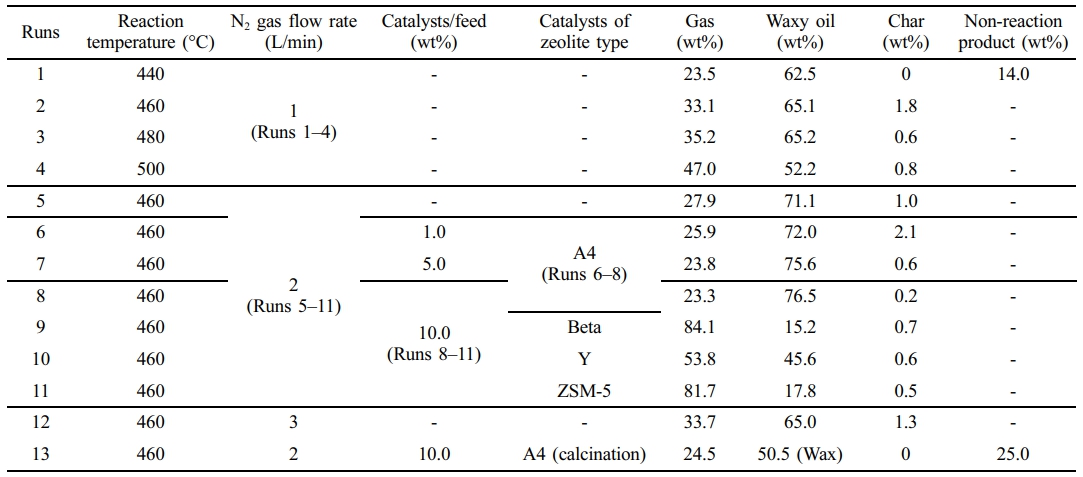

Reaction Conditions. The waste PE fraction was loaded into a container in the fixed-bed reactor. The container, made of stainless steel, is cylindrical with a volume of 0.65 L. The pyrolysis temperatures in the experiments were based on the TGA results of the waste PE fraction, conducted between 440 and 500 ℃. The nitrogen gas flow rates were 1 and 2 L/min. The catalyst was mixed with the waste PE fraction and introduced into the reactor. To compare the effects of the catalysts, 20 g (10 wt% of the sample) was employed. The catalysts were then mixed with the sample and introduced into the reactor. The heating rate of the pyrolysis reactor was about 16 ℃/min. The gas residence time in the pyrolysis reactor was calculated by about 163 seconds in a cold state. Each experiment was conducted for 2 h. The reaction conditions are shown in Table 5. Runs 1 to 4 focused on the pyrolysis of waste PE as influenced by reaction temperature. Run 5 examined the impact of increased nitrogen gas flow at the optimized reaction temperature for the maximum yield of waxy oil. Runs 6 to 8 investigated the changes in the mass balance of the products with varying amounts of A4 zeolite. Runs 8 to 11 observed the mass balance and product characteristics resulting from the catalytic pyrolysis of waste PE using ion-exchanged A4 zeolite and other zeolites with different acid sites and structures, such as Beta, Y zeolites, and ZSM-5. Several of the experiments were repeated to obtain better results. After the pyrolysis reaction, the products were collected in the hopper of the quenching system. The mass balances for the experiments are shown Supporting Information.

Zeolite Catalysts. Zeolite catalysts play a crucial role in pyrolysis by enhancing product yield and selectivity due to their distinct structure, acidity, and porosity. These crystalline microporous aluminosilicates contain framework alumina (AlO2) units with acidic active sites, influencing their catalytic performance. Their efficiency depends on acid site and strength. This study compared the performance of four zeolites (A4, Beta, Y, and ZSM-5, Zeolyst Co. Ltd., USA) with different acidity and pore structures, to evaluate their impact on pyrolysis waxy oil from waste PE. A4 zeolite, with an 8-membered ring structure and a small pore size (~4.1 Å), functions as a molecular sieve with strong ion-exchange capacity, selectively separating molecules by size.37 Beta zeolite, known for its three-dimensional pore network and high thermal stability, is effective in cracking complex molecules, as demonstrated in lignocellulosic bio-oil hydroprocessing.38 Y zeolite, with a larger pore size (~7.4 Å) and a 12-membered ring, accommodates bulkier molecules, making it suitable for processing aromatics, alkanes, and cycloalkanes.39 ZSM-5, recognized for its shape-selective catalysis and high thermal stability, facilitates the conversion of PE-derived waxes into high-value hydrocarbons, owing to its robust framework and acidic sites.40

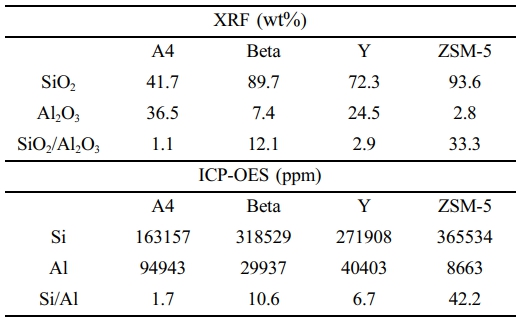

The acidities of the zeolites were determined by X-ray Fluorescence (XRF; semi-quantitative) and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES; quantitative) analyses. The results are presented in Table 3.

The acid strengths of the catalysts, as indicated by the Si/Al ratio, increase in the order of A4 < Y < Beta < ZSM-5, whereas the total acidities, related to the number of acid sites, may decrease in this order.

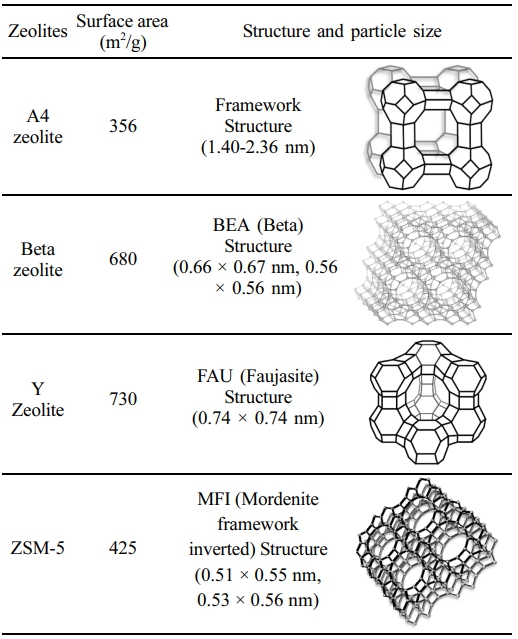

In addition to their chemical composition, the physical properties such as surface area, framework structure, and particle size of the zeolites are summarized in Table 4.

Analysis of the Products. This study mainly compares the characteristics of waxy oil produced through varying reaction temperatures and catalytic pyrolysis. Two analysis methods were employed to compare the characteristics of the waxy oil. To identify the compounds and classify the hydrocarbons, such as paraffin and olefin, present in the products, a GC/MS (7890A 5975C, Agilent Instruments, USA) analysis was performed. This method enables the analysis of samples with a boiling range that extends to a final boiling point (FBP) exceeding 250 °C. In general, hydrocarbons have a respecter of 1 in GC/MS analysis, but heteroatoms are different. Also, since it is not an accurate semi-quantitative analysis method, it was analyzed to compare the approximate distribution of some of the compounds. In the GC/MS analysis conditions of waxy oil, the sample was filtered through a 0.45 µm Teflon filter after dissolution. The solvent used for the analysis was chloroform. The sample was diluted with this solvent before being injected. The A DB-5MS UI column was used with a 1 mL injection at a 10:1 split ratio. The helium (1.0 mL/min) was used as the carrier gas, and the analysis was conducted in scan mode with a molecular weight range of 30–500 m/z. To investigate the boiling point and paraffin content characteristics of this waxy oil, a SIMDIS (8890GC, Agilent Instruments, USA) analysis was conducted. Generally, the SIMDIS analysis was performed to examine the boiling point distribution of the synthetic crude oil. In the SIMDIS analysis of waxy oil, the C8 above hydrocarbons were analyzed using the standard method of ASTM D7169. This method enables the analysis of samples with a boiling range that extends to a FBP exceeding 720 ℃. The carbon number distribution results obtained from SIMDIS analysis can detect hydrocarbons with a carbon number of 120 (C120). When a sample is injected, it passes through a high-temperature gas chromatograph column and is separated. The compounds are detected in order from the lowest boiling point to the highest boiling point. The detection time of each compound can be related to the boiling point to simulate the boiling point distribution of the sample, which allows quantitative analysis of compounds with carbon numbers up to C120. In the SIMDIS analysis conditions, wax oils were diluted with carbon disulfide (CS2).

The pyrolysis gases were analyzed by gas chromatography-thermal conductivity detection (GC-TCD: 7890 A, Agilent Instruments) and flame ionization detection (GC-FID). For GC-TCD analysis, a Carboxen 1000 column was applied, and argon was used as the reference and carrier gas. For GC-FID analysis, an HP-Plot aluminum oxide (Al2O3) / potassium chloride (KCl) column was used. Argon gas was used as a supplementary gas at a flow rate of 25 mL/min. The oven temperature was maintained at 40 ℃ for 4 min, then increased to 160 ℃ at 4 ℃/min, and then to 200 ℃ at 2 ℃/min. It was maintained at this temperature for 30 min.

|

Figure 1 Experimental schematic diagram of pyrolysis system. |

|

Figure 2 The TG curves of waste PE fraction. |

|

Figure 3 The DTG curves of waste PE fraction. |

|

Table 1 Proximate and Ultimate Analyses of Waste PE |

a By difference, b Ash-free basis, c Less than 0.01 |

|

Table 5 The Experimental Conditions and Results of Mass Balance from Pyrolysis Products |

The experimental conditions and yield results are summarized in Table 5. In this experiment, wax oil was defined as containing C7 to C35, and hydrocarbons containing carbon atoms larger than C19 are defined as wax. Runs 1–4 involved experiments with varying reaction temperatures, while Run 5 was conducted by increasing the N2 flow rate under optimal yield conditions. Runs 6–8 were performed to compare the quantity of A4 zeolite used, and Runs 8–11 involved experiments with different zeolites under optimal yield conditions. In Run 13, waste PE pyrolysis was performed by calcining A4 zeolite. In some experiments (Run 5), the yields of waxy oil that did not conform to the trend were observed, necessitating re-experimentation. The waxy oil yield in Run 5 was 71.1 wt%, with a standard deviation of ± 1.1 wt%. This showed that the yield ranged from 70.0 to 72.2 wt%. The standard deviation obtained through such re-experimentation indicated the repeatability of the experiment and the reliability of the results.

When non-catalyst was used, the maximum yield of waxy oil was 71.1 wt% in Run 5. This was because the highest yield of waxy oil was obtained at a reaction temperature of 460 ℃. This temperature was selected, and the nitrogen gas rate variable was set. In Run 12, the nitrogen gas rate was 3L/min, but the yield of waxy oil was reduced to 65 wt%. Therefore, this pyrolysis system was optimal when the nitrogen gas rate was 2 L/min. The catalytic pyrolysis experiment was performed under these yields of optimum conditions. When A4 zeolite was used, the maximum yield of waxy oil product was about 76 wt% in Run 8.

This outcome is primarily attributed to the ion exchange reaction facilitated by the Na+ metal-ion in A4 zeolite and the adsorption effects of its micro-sized pores. The maximum yield of gas product was 84.1 wt% in Run 9. This high yield can be attributed to the channel-type structure and selectivity characteristics of ZSM-5. The linear structure of waste PE further facilitated rapid gas conversion through accelerated reactions.

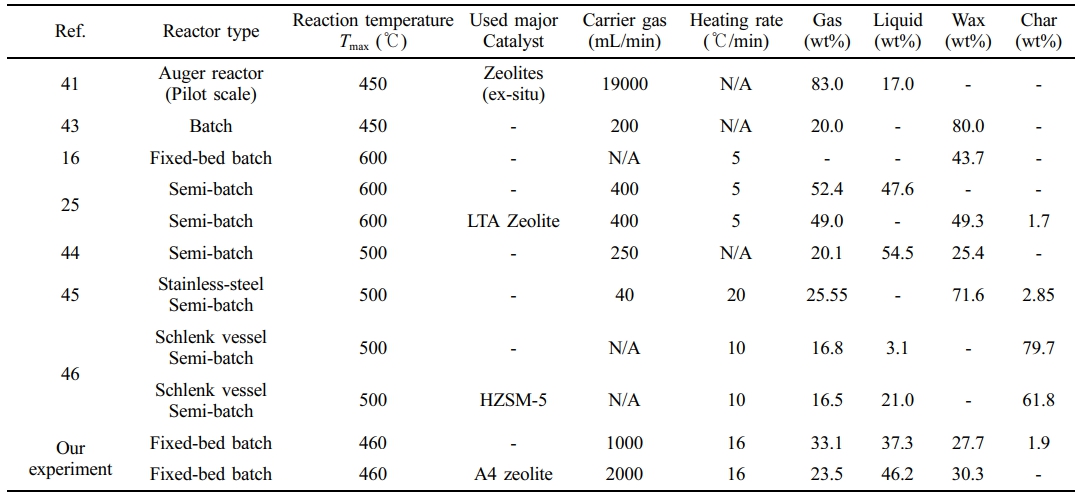

Table 6 compares the results of polyethylene pyrolysis from various studies. Most studies were conducted in batch reactors with reaction temperatures ranging from 450 to 600 ℃. Netsch, N. et al. studied the pyrolysis of polyolefin waste using various zeolite and silica-alumina catalysts to obtain high yields of gas and liquid. In particular, it was shown that the catalytic reaction at 400–550 ℃ promoted the production of high-value compounds such as C2–C4 olefins.41 Rodríguez et al. performed the heating rate of the reactor at 20 ℃/min, which is higher than that used in our pyrolysis reactor. This higher heating rate led to a wax yield of 71.6 wt%.45 An increase in the heating rate of the reactor leads to higher wax yields. A higher heating rate causes polymer chains to break down rapidly, leaving behind a significant amount of partially decomposed intermediates. These intermediates are likely to remain as wax substances with high molecular weight. Therefore, increasing the heating rate leads to higher waxy product yield at approximately 500 ℃.42 The yield of waxy oil varies depending on the reactor type, flow rate of carrier gas, and reaction temperature.

Mass Balance of Pyrolysis Products. The mass balance of the pyrolysis products was evaluated under various conditions and is summarized in the Supporting information (Figures S1–S3). Figure S1 shows the product yields as a function of reaction temperature, highlighting changes in gas, waxy oil, and char fractions. Figure S2 presents the influence of nitrogen gas flow rate on waxy oil yield at 460 ℃. Figure S3 compares the product distributions obtained using different zeolite catalysts under identical reaction conditions.

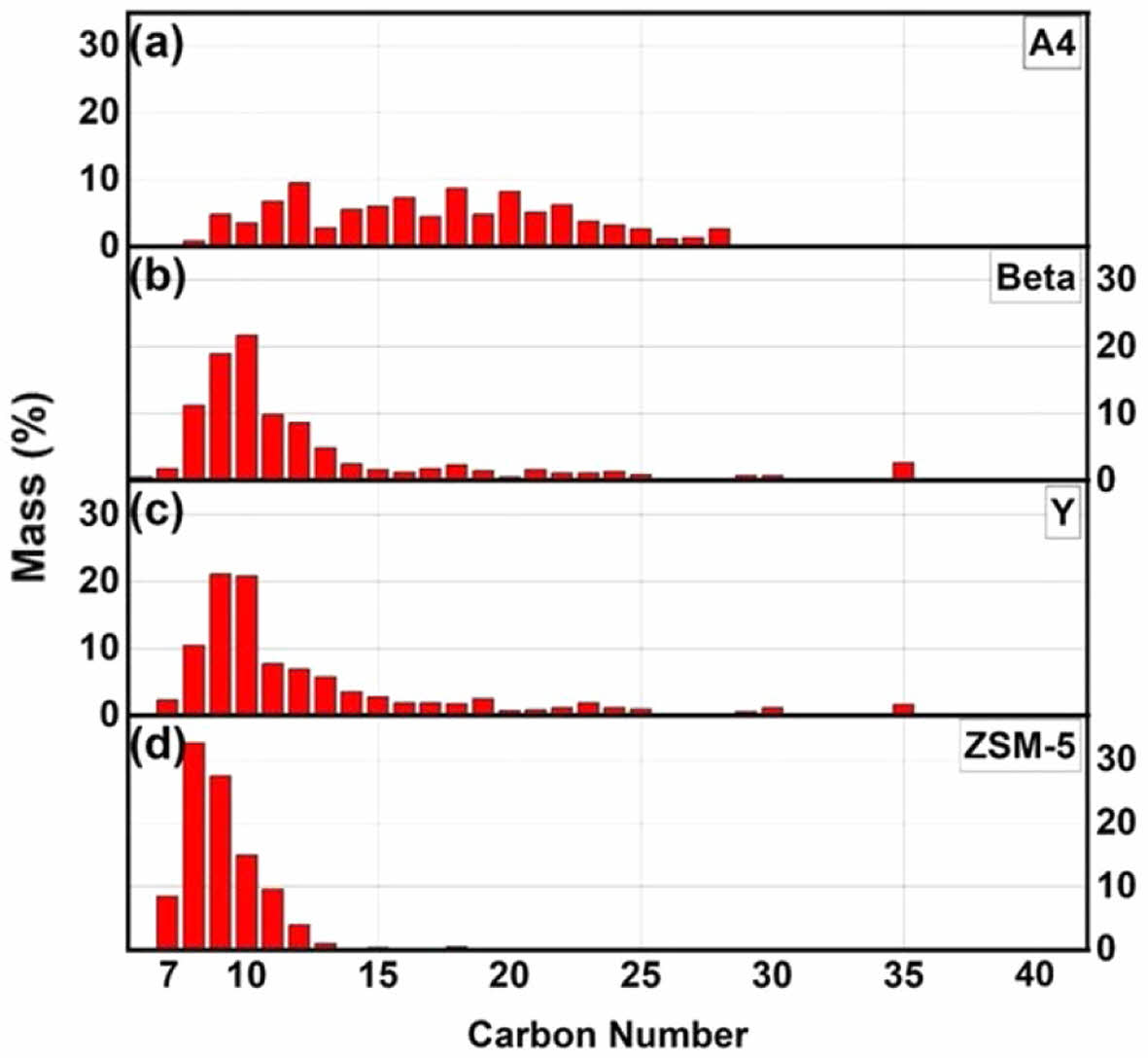

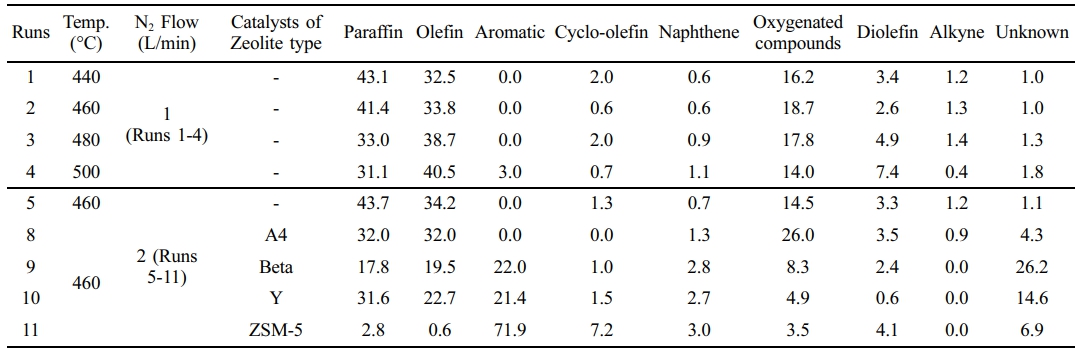

Results of GC/MS analysis. GC/MS analysis was conducted for oil components with boiling point below 250 ℃. Therefore, waxes with higher boiling points are generally not analyzed. Thus, this section could identify only some of the compounds of the pyrolysis oil with boiling points below 250 ℃. The distribution of recovered pyrolysis waxy oils was investigated based on the number of carbons. Additionally, the compounds within this range of oil were classified, such as aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, and the peak area values were expressed as percentages.

Figure 4 illustrates the compound distribution of catalytic pyrolysis products as a function of carbon number. The distribution appears broad in Figure 4(a), whereas in Figure 4(d), it was distributed sharply on carbon numbers of the lower range. Figures 4(b)-(d) are composed of light hydrocarbons below C15. On the other hand, Figure 4(a) is composed of various hydrocarbons below C28 and is considered to be suitable as a base resource for lubricating oil. The results of GC/MS were conducted to determine the specific components of the pyrolysis waxy oil. The qualitative GC-MS results based on peak area were converted to quantitative values expressed as weight/mass percentages using internal standards and correction factors. Table 7 illustrates the composition ratios of compounds classified into paraffin, olefin, aromatic, cyclo-olefin, naphthene, diolefin, and alkyne groups. The oxygenated compounds were mainly composed of alcohol.47 The classification of hydrocarbon types in pyrolysis oil products follows ASTM D2425.48 The paraffin content decreases as the reaction temperature increases. At 440 ℃ in Run 1, the paraffin content was 43.1%, but it reduced to 31.1% at 500 ℃ in Run 4. This decline suggests that higher temperatures promote the cracking of paraffinic hydrocarbons into smaller molecules such as olefins and diolefins. The olefin content shows an increasing trend with temperature. Starting from 32.5% in Run 1 at 440 ℃, it rose to 40.5% in Run 4 at 500 ℃. Olefins are valuable intermediates in petrochemical processes due to their reactivity.11 Increasing olefin content at higher temperatures indicates enhanced dehydrogenation and cracking reactions, forming more unsaturated hydrocarbons.49 Aromatic compounds begin to form significantly at higher temperatures and in the presence of specific catalysts.50 While non-aromatics were detected in Runs 1 to 3, the aromatic content reached 3.0% in Run 4 at 500 ℃. The use of zeolite-type catalysts dramatically increases the aromatic content. Run 9 with Beta zeolite yielded 22.0% aromatics, and Run 11 with ZSM-5 produced a substantial 71.9% aromatic content. This enhancement is attributed to the catalytic activities of zeolites, which promote dehydrocyclization and aromatization reactions.51 Cyclo-olefin content varies with both temperature and catalyst type. It remained relatively low at lower temperatures but increased in Runs involving zeolite catalysts. Run 11 with ZSM-5 catalyst showed a cyclo-olefin content of 7.2%. This suggests that catalytic conditions favor the formation of cyclic unsaturated hydrocarbons through cyclization reactions.11 Naphthene content, representing cycloalkanes, shows slight variations across different runs. It remained below 1.1% in most cases but increased to 3.0% in Run 11 with the ZSM-5 catalyst. The presence of naphthenes indicates that hydrogenation of aromatic rings or cyclization of aliphatic chains may occur under certain catalytic conditions. Oxygenated compounds exhibit notable increases under specific conditions. In Run 1 at 440 ℃, the oxygenated compound content was 16.2%, which decreased with increasing temperature, dropping to 14.0% in Run 4 at 500 ℃. However, using specific catalysts like A4 zeolite in Run 8 elevated the oxygenated compound content to 26.0%. This increase may result from the catalyst facilitating the incorporation of oxygen into the hydrocarbon framework or from the decomposition of oxygen-containing additives in the waste polyethylene. The oxygenated compounds were mainly composed of alcohol.47 The diolefin content increased with rising reaction temperatures. In Run 4, the diolefin content reached its highest value of 7.4%.

The presence of naphthenes indicates that hydrogenation of aromatic rings or cyclization of aliphatic chains may occur under certain catalytic conditions. Oxygenated compounds exhibit notable increases under specific conditions. In Run 1 at 440 ℃, the oxygenated compound content was 16.2%, which decreased with increasing temperature, dropping to 14.0% in Run 4 at 500 ℃. However, using specific catalysts like A4 zeolite in Run 8 elevated the oxygenated compound content to 26.0%. This increase may result from the catalyst facilitating the incorporation of oxygen into the hydrocarbon framework or from the decomposition of oxygen-containing additives in the waste polyethylene. The oxygenated compounds were mainly composed of alcohol.52 The diolefin content increased with rising reaction temperatures. Specifically, at a reaction temperature of 500 ℃ in Run 4, the diolefin content reached its highest value of 7.4%. The increased presence of diolefins is notable because they are more reactive species that can participate in additional chemical transformations, potentially enhancing the value of the pyrolysis products.47 These results demonstrate that reaction conditions significantly influence the composition of pyrolysis products from waste polyethylene. Higher temperatures favor the formation of unsaturated hydrocarbons like olefins and diolefins, while zeolite-type catalysts promote the production of aromatics and cyclo-olefins. Understanding the distribution of these hydrocarbon groups is crucial for optimizing the pyrolysis process. Adjusting reaction temperatures and selecting appropriate catalysts allows the product composition to be tailored toward specific hydrocarbons of higher economic value.

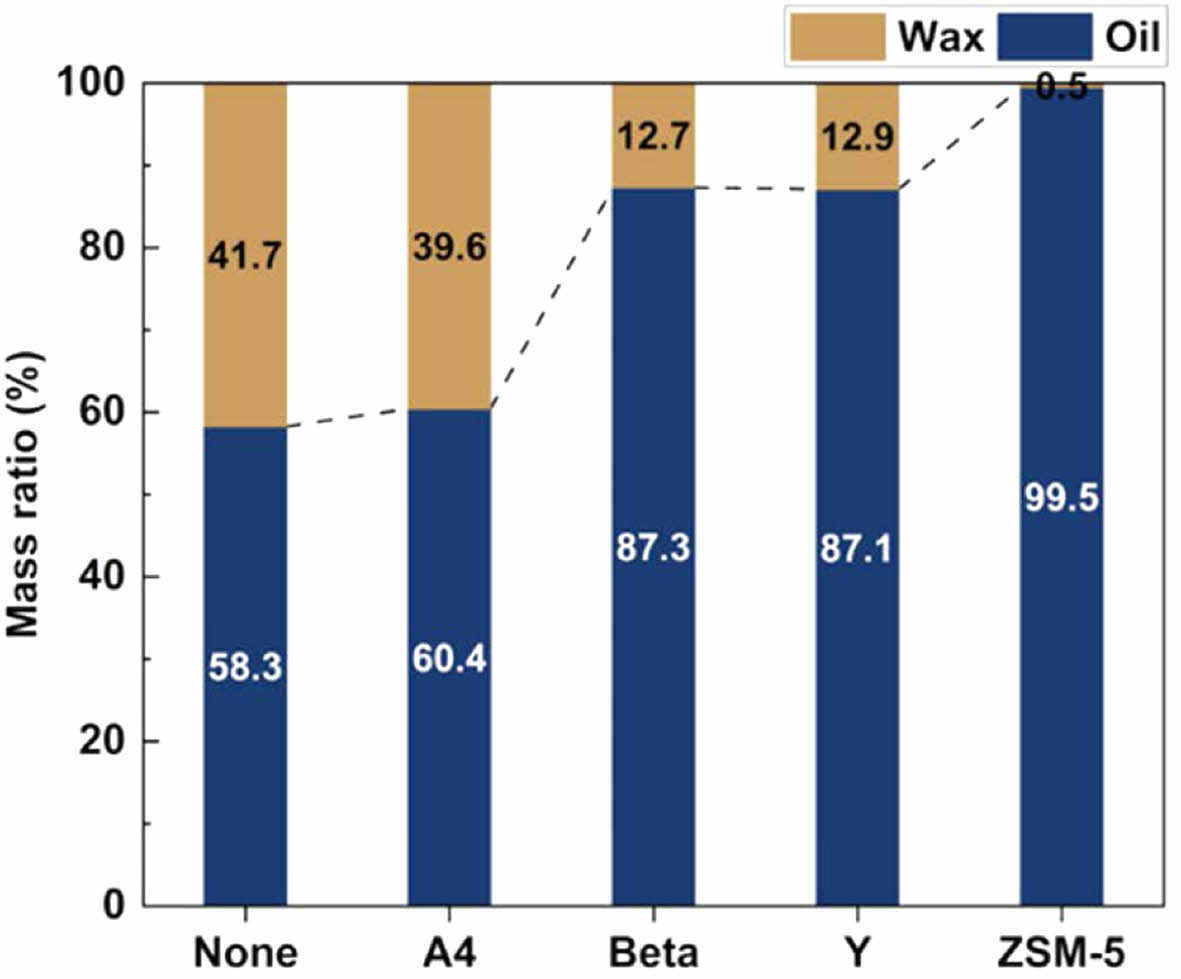

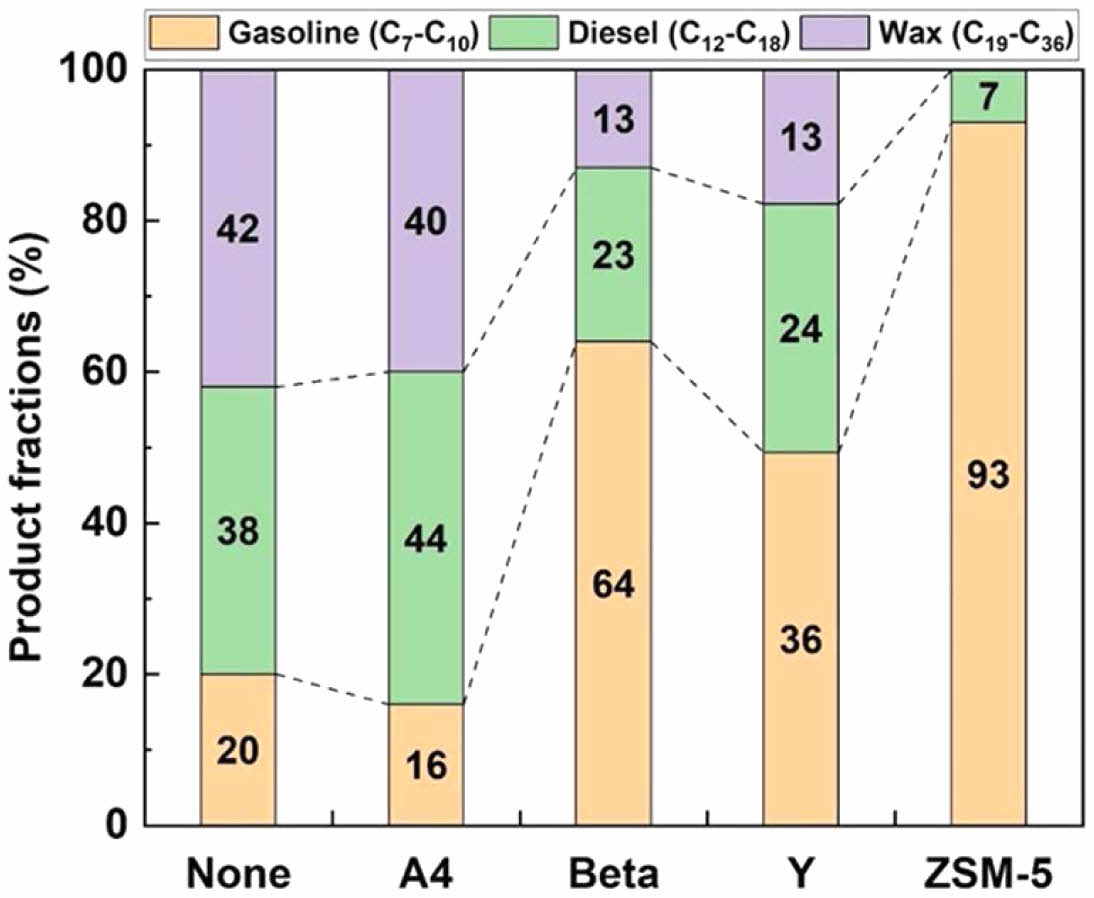

Classification of Recovered Wax Based on Different Methods: Figure 5 shows the catalytic pyrolyzed waxy oil classification based on a range of carbon numbers. The products were categorized into wax and oil using the petrochemical process.48

Notably, an increase in the Si/Al ratio improves the conversion rate to oil. The yields of oil and wax (C19 and above) were categorized based on GC/MS analysis results from the mass balance of waste PE pyrolysis with various zeolite catalysts.

The Beta and Y zeolites yielded notably low ratios of wax at 12.7 and 12.9%, respectively, attributed to extensive cracking reactions resulting from acid-catalytic processes. However, when ZSM-5 was used, non-wax was produced. Conversely, using an A4 zeolite resulted in a significantly higher ratio of wax yield of 39.6%, respectively. Figure 6 classifies waxy oils from catalytic pyrolysis via waste PE based on the petrochemical fuel range.

The classified data within the fuel range is helpful as a reference for incorporating pyrolysis wax into the lubricant-based oil production process. With A4 zeolite, recovered wax was abundant, constituting 40% of the product. When using the Beta and Y zeolites, a wax of 13% was produced. In contrast, ZSM-5 did not yield any wax due to its selectivity. These compositions predominantly consisted of compounds with fewer gases or carbon atoms due to the rapid reaction of pyrolysis gases from the linear waste PE sample. The Beta and Y zeolites, possessing super-cages with mesopores, underwent cracking reactions based on active site distribution, determining wax yield. Conversely, A4 zeolite, with micropores, generated a significant amount of wax in pyrolysis waxy oil products due to lower active site distribution compared with Beta and Y zeolites.

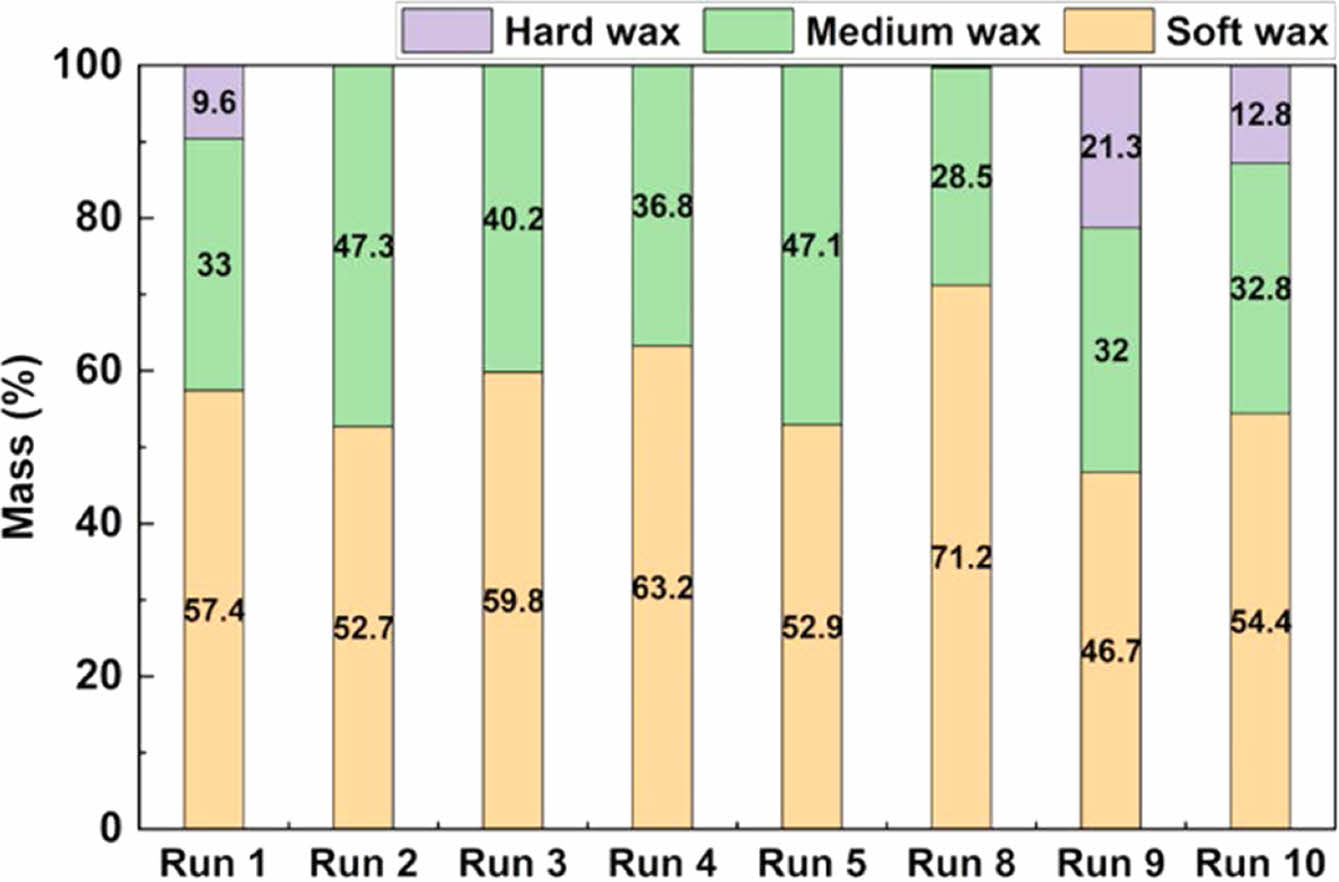

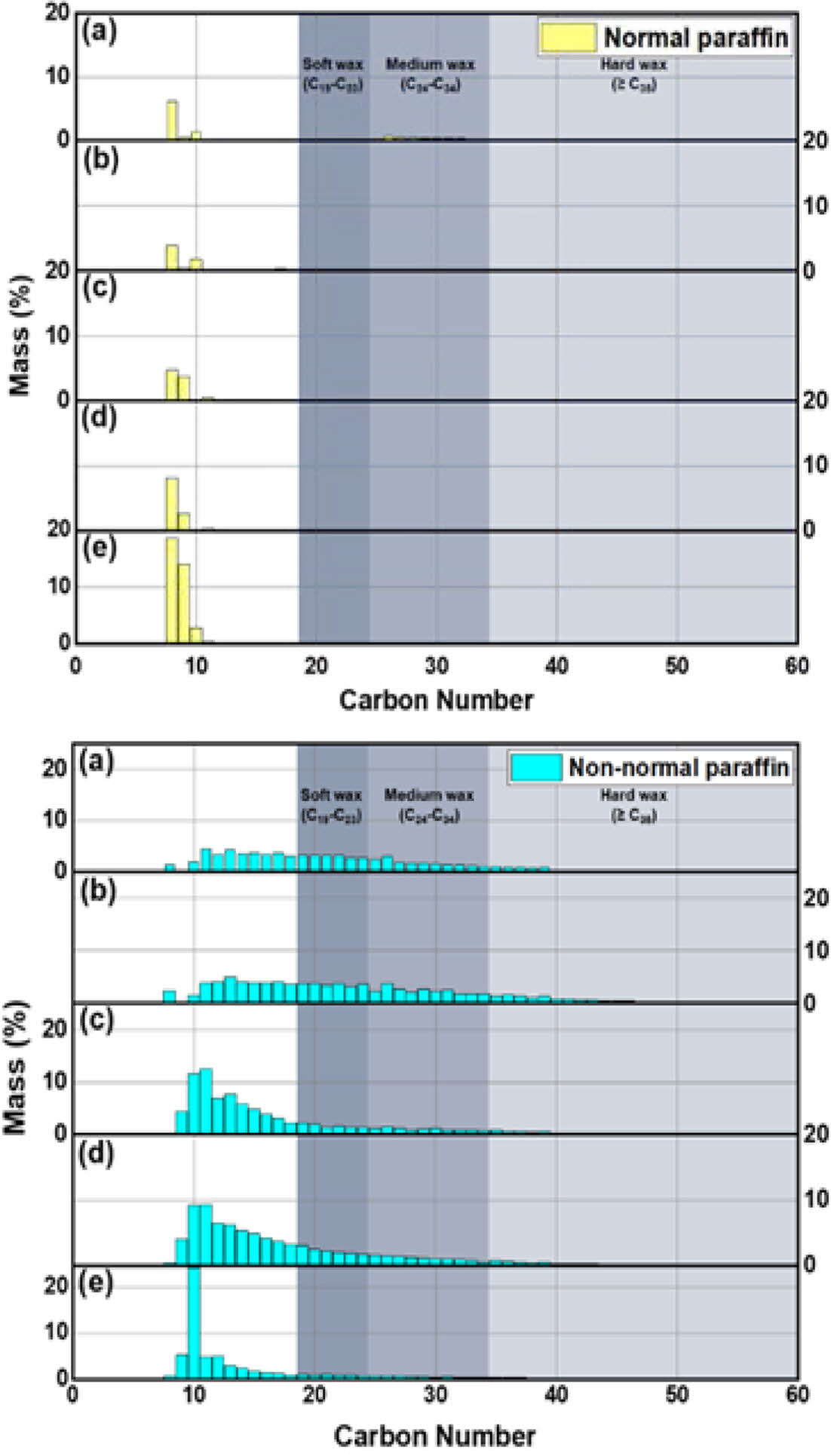

Figure 7 illustrates the distribution of wax products resulting from pyrolysis based on carbon number. The experimental conditions of the runs are specified in Table 5. Waxes were categorized into soft wax (C19–C23), medium wax (C24–C34), and hard wax (³C35).53 Runs 1–4 represent wax distribution at reaction temperatures of 440, 460, 480, and 500 ℃, with Run 5 having a reaction temperature of 460 ℃ with a nitrogen flow rate of 2 L/min. As the reaction temperature increased, soft wax yield also increased due to the molecular cracking reaction activity. when the nitrogen gas flow rate was at 2 L/min, the soft wax (Run 5) was similar to 1 L/min (Run 2). In addition, Run 1 had hard wax at 9.8%, including unreacted material. This was due to the low reaction temperature. As a result, the product containing unreacted material had a lower soft wax distribution and a higher medium wax distribution.

In the absence of a catalyst, soft and medium wax accounted for 52.7–63.2% and 33.0–47.3% of the product, respectively, whereas hard wax was not generated, except at a reaction temperature of 440 ℃. Runs 8 to 10 represent the recovered wax distributions after catalytic pyrolysis using A4, Beta, and Y zeolites. Figure 11, in which ZSM-5 (Run 11) was applied, was excluded because wax was not produced. The Beta zeolite has a three-dimensional cross-pore structure. This porous structure allows for the control of various molecular sizes. As a result, soft, medium, and hard waxes were distributed at 46.7, 32.0, and 21.3%, respectively. On the other hand, Y zeolite has a Faujasite (FAU) structure, which forms a large super-cage. This super-cage has large pores and can be accessed through the pore entrance consisting of 12 oxygen atoms. This structure allows molecules of various sizes to enter. Due to the presence of oxygen atoms, the distribution of soft, medium, and hard waxes was 54.4, 32.8, and 12.8%, respectively. Conversely, the hard wax was not produced when A4 zeolite was used. The structure of A4 zeolite has small pores composed of 8 oxygen atoms. This structure gives it the property of adsorbing or excluding only certain molecules depending on their size. Because of this, A4 zeolite is mainly used to filter out molecules less than 4 Å. This property of A4 zeolite is a selective adsorption reaction that does not allow large molecules to pass through. As a result, the soft wax of Run 8 was distributed at about 71.2%, which was 18.3

% more distributed than the waxy oil of pyrolysis without a catalyst (Run 5). This soft wax has a carbon chain length ranging from C19 to C23, which is ideal for lubricant base oils. Hydrocarbons with these provide high viscosity while maintaining sufficient fluidity, which is crucial for lubrication. Additionally, the relatively low boiling point of the soft wax makes it easier to obtain lubricant base oils during subsequent refining and separation processes, improving processing efficiency and increasing the yield of the desired lubricant products. The narrow and uniform hydrocarbon distribution within the C19-C23 range enables the production of consistently high-quality lubricant base oils, contributing to the performance and stability of the lubricants.28 This property makes it especially suitable for producing high-value products like engine oils and industrial lubricants. Additionally, the low volatility of this wax enhances environmental safety and provides notable economic benefits by minimizing base oil loss.

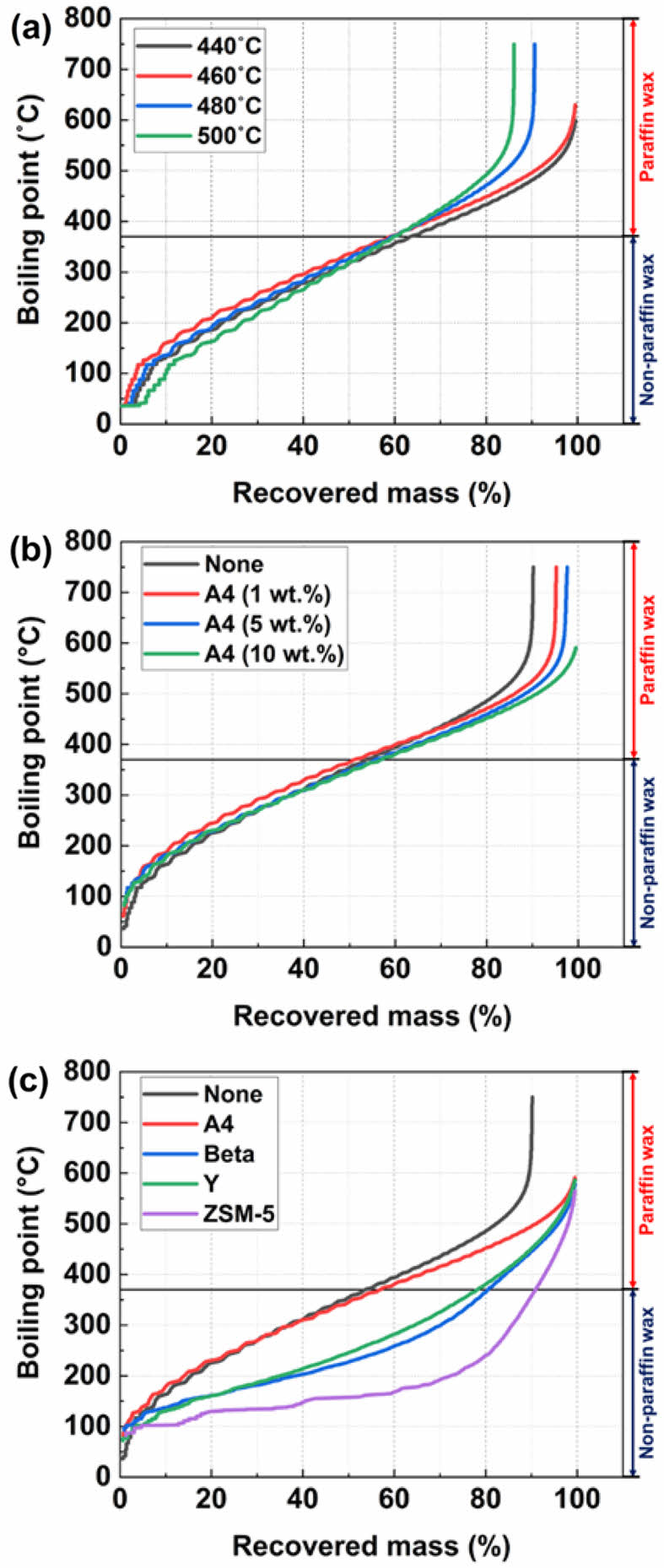

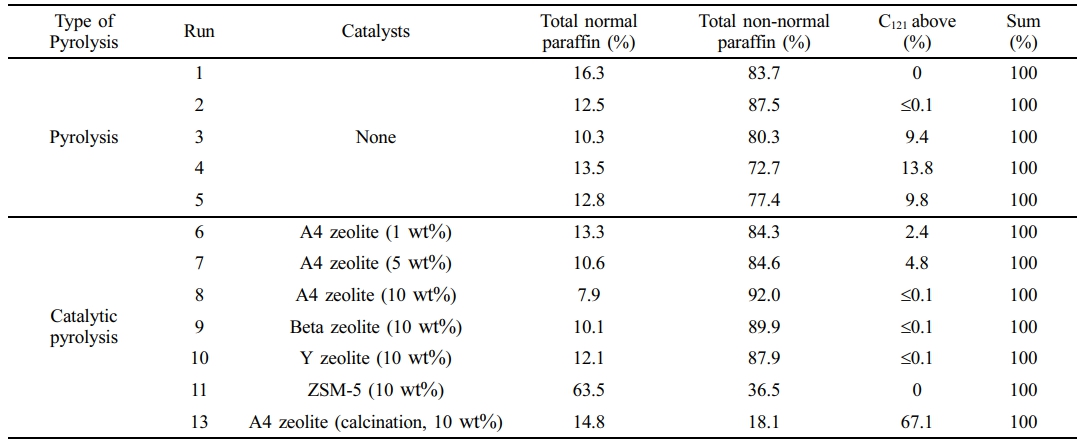

Results of SIMDIS Analysis. The waxy oil was analyzed to compare the waxy oil distribution based on boiling points and paraffin content characteristics, the primary hydrocarbon of waxy oil. The paraffin content identifies the distribution between normal and non-normal forms of paraffin in waxy oil. This information is valuable as it provides insights into the suitability of waxy oil as a feedstock for lubricant-based oil production processes.

Boiling Point Distribution of the Recovered Waxy Oils: Figure 8 shows the SIMDIS analysis results for the boiling point of the waxy oil from waste PE. Figure 8(a) illustrates the trend in waxy oil boiling points with varying pyrolysis temperatures. The boiling point curves for Runs 1 and 2 show that the recovered mass of waxy oil reached 99.5% at 600 and 630 ℃, respectively. In contrast, for Runs 3 and 4, the recovered mass of waxy oils reached 86 and 90% at 750 ℃. This indicates that compounds with higher boiling points are produced as the reaction temperature increases. Figure 8(b) shows the effect of A4 zeolite content on the boiling point distribution. As the amount of A4 zeolite increases, the boiling point distribution shifts slightly to lower boiling points. This indicates an increase in the lighter hydrocarbon fraction. The A4 zeolite (10 wt%) curve shows the largest decrease in the boiling point range. This suggests that higher zeolite loading promotes more active cracking, converting heavy hydrocarbons to lighter fractions. Therefore, as the amount of A4 zeolite increases, the boiling point of the product decreases. This indicates that more effective catalytic decomposition occurs. A4 zeolite (10 wt%) produces more low-boiling compounds, showing that more light hydrocarbons are produced.

Figure 8(c) compares the effect of different zeolite types (A4, Beta, Y, ZSM-5) on the boiling point distribution of pyrolyzed waxy oils. The presence of zeolites generally shifts the boiling point distribution toward lower boiling points, particularly in the case of ZSM-5, which exhibits the most dramatic shift. The ZSM-5, due to its microporous structure and high acidity, promotes significant cracking of heavy hydrocarbons, producing a higher fraction of light fractions. The ZSM-5 was the most effective catalyst for reducing the boiling point, producing the largest fraction of light hydrocarbons. The Y and Beta zeolites exhibit moderate cracking activity compared to ZSM-5. Thus, the Beta, Y, and ZSM-5 zeolites appear to be suitable for oil and gas upgrading. On the other hand, the A4 zeolite was the least effective in terms of shifting the boiling point distribution. This variation indicates the dependence of the pyrolysis boiling point of waxy oil distribution on the reaction temperature, rate of nitrogen flow, and catalyst amount. Freund et al. reported the boiling point of paraffinic wax.54 The boiling point of paraffin wax is indicated by a solid line (³ 370℃) in Figure 8.

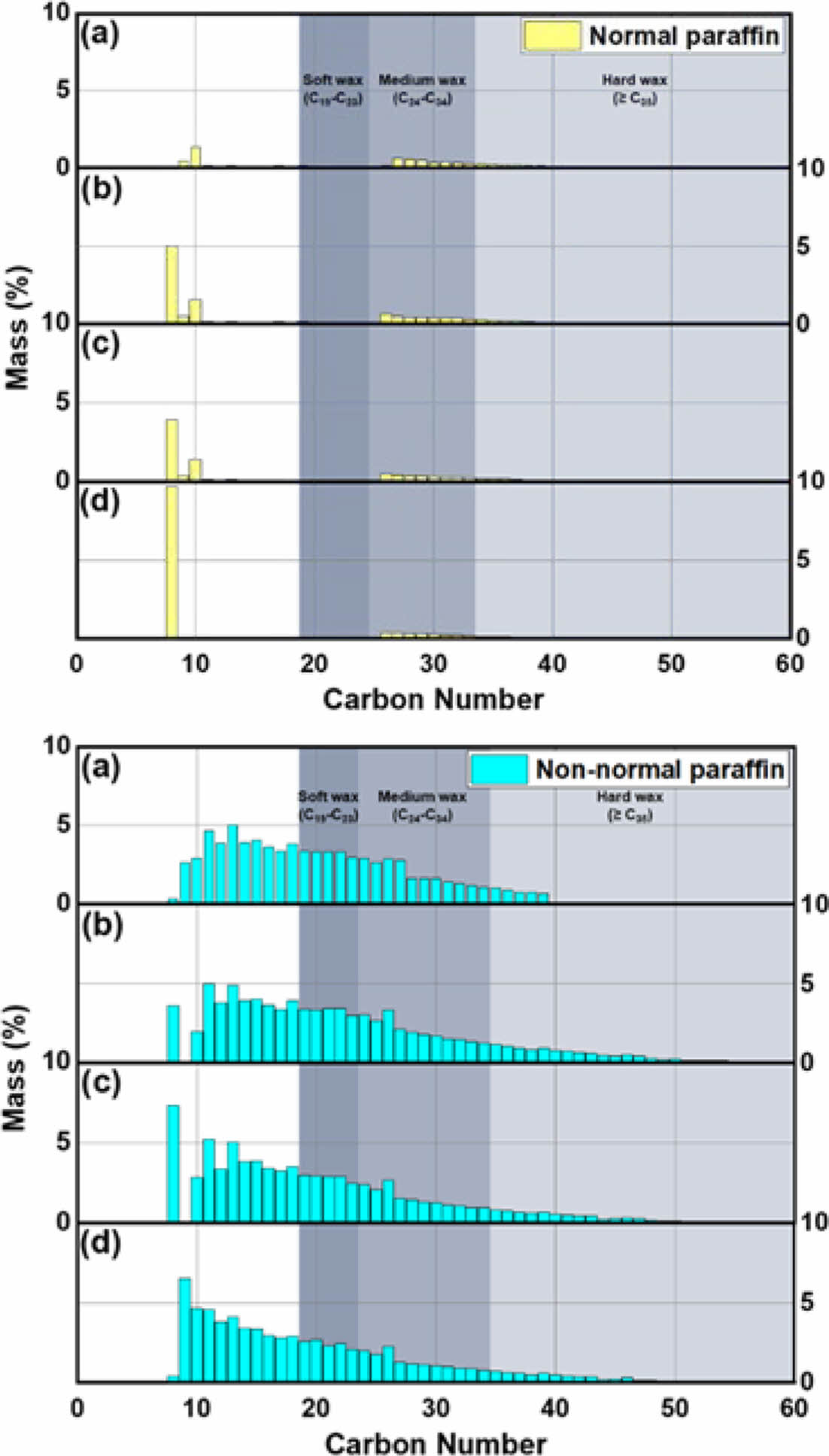

Paraffin Distribution in the Recovered Waxy Oils: Figure 9 illustrates the content distribution of normal and non-normal paraffins at reaction temperatures ranging from 440 to 500 ℃ during SIMDIS analysis.

At a reaction temperature of 500 ℃, the normal paraffin in C8 increases to around 9.8%, while the non-normal paraffin content decreases significantly, most likely because it is converted into normal paraffin. Non-normal paraffin content increases, indicating a reduction likely resulting from beta-scission reactions.55 Except for C8, there were no notable variations in the normal and non-normal paraffin content as the reaction temperatures varied.

Figure 10 presents the paraffin form distribution when using a catalyst, ranging from C8 to C60. Without a catalyst, C8 paraffin primarily comprises normal paraffin (approximately 6%), while from C10 to C50, non-normal paraffins dominate. When using A4 zeolite, the normal paraffin of C8 in this waxy oil was reduced by half compared to pyrolysis without a catalyst. In addition, normal paraffins at C26-C34 were converted to non-normal paraffins. The Beta and Y zeolites exhibit normal paraffin forms for compounds below C10, transitioning to non-normal forms for C11 and above, indicating the influence of micropores and super-cages. The higher content of normal paraffin when using ZSM-5 is due to the improved selectivity towards linear compounds.

Table 8 presents the wax content from the SIMDIS analysis of pyrolysis waxy oil. Runs 1-4 analyzed waxy oil pyrolyzed under nitrogen gas at 1 L/min without a catalyst. Run 2 involves waxy oil pyrolyzed at a reaction temperature of 460 ℃. The maximum concentration of non-normal paraffin in these waxy oils was approximately 87.5%. This outcome suggests that increasing the reaction temperature in the pyrolysis system minimizes the conversion of waxy oil into non-normal paraffin. It also suggests that the long-chain hydrocarbons in waste polyethylene were not cracking reactions into shorter chains at higher reaction temperatures. Therefore, the primary reaction of pyrolysis predominantly occurs at lower temperatures (around 440 ℃), cracking long-chain hydrocarbons into smaller alkanes and alkenes. In contrast, at 500 ℃, secondary cracking and condensation reactions become more prominent. These reactions could form heavy-molecular-weight hydrocarbons through mechanisms such as the recombination of lighter molecular fragments, aromatic condensation, or olefin reactions.56 This explains the increase in the C121 compounds above, which was from 0 to 13.8%.

Runs 8-11 performed catalytic pyrolysis of waste PE in situ. In Run 8, when A4 zeolite was used, the non-normal paraffin content in the waxy oil reached a maximum of 92%. Compared to Run 5, where pyrolysis was performed without a catalyst under identical conditions, the non-normal paraffin content increased by approximately 15%, from 77.4 to 92%. This enhancement can be attributed to the cracking of A4 zeolite from acid sites, allowing cracking to occur primarily through adsorption rather than acid-induced cracking. In Runs 9 and 10, where Beta and Y zeolites were used as catalysts, non-normal paraffin contents were 89.9 and 87.9%, respectively. The Beta and Y zeolites have acid site densities of 10.6 and 6.7%, with BEA and FAU frameworks, respectively. This contributes to their higher reactivity and enhanced cracking due to acid sites and mesoporous structures. In contrast, Run 11, which used ZSM-5, exhibited a significantly lower non-normal paraffin content of 36.5%. The reduced content is likely due to the channel-like structure and high selectivity of ZSM-5, which promotes increased reactivity of linear polymers. In Run 13, when calcined A4 zeolite was used, normal and non-normal paraffins were 14.8 and 18.1%, respectively. Also, ultra-long-chain paraffins (C121 and above

) had the highest proportion at 67.1%. The comparison of SIMDIS results with and without catalyst calcination is presented in Supporting Information (Figures S4–S5).

Runs 8-11 performed catalytic pyrolysis of waste PE in-situ. In Run 8, when A4 zeolite was used, the non-normal paraffin content in the waxy oil reached a maximum of 92%. Compared to Run 5, where pyrolysis was performed without a catalyst under identical conditions, the non-normal paraffin content increased by approximately 15%, from 77.4 to 92%. This enhancement can be attributed to the cracking of A4 zeolite from acid sites, allowing cracking to occur primarily through adsorption rather than acid-induced cracking. In Runs 9 and 10, where Beta and Y zeolites were used as catalysts, non-normal paraffin contents were 89.9 and 87.9%, respectively. The Beta and Y zeolites have acid site densities of 10.6 and 6.7%, with BEA and FAU frameworks, respectively. This contributes to their higher reactivity and enhanced cracking due to acid sites and mesoporous structures. In contrast, Run 11, which used ZSM-5, exhibited a significantly lower non-normal paraffin content of 36.5%. The reduced content is likely due to the channel-like structure and high selectivity of ZSM-5, which promotes increased reactivity of linear polymers. In Run 13, when calcined A4 zeolite was used, normal and non-normal paraffins were 14.8 and 18.1%, respectively. Also, ultra-long-chain paraffins (C121 and above) had the highest proportion at 67.1%.

|

Figure 4 Carbon distribution of the products after catalytic pyrolysis of waste PE (Runs 8 to 11). |

|

Figure 5 Classification of wax and oil based on carbon number. |

|

Figure 6 Classification of the petrochemical fuel range for catalytic pyrolysis waxy oils. |

|

Figure 7 Classification of wax from pyrolysis waxy oils. |

|

Figure 8 SIMDIS analysis results of the pyrolysis waxy oil based on (a) reaction temperature; (b) the amount of A4 zeolite; (c) zeolite types. |

|

Figure 9 The paraffin content under reaction temperatures of (a) 440; (b) 460; (c) 480; (d) 500 ℃. |

|

Figure 10 The paraffin contents: (a) without and using zeolite catalysts; (b) A4; (c) Beta; (d) Y; (e) ZSM-5. |

|

Table 6 Comparison of Mass Balance Results for Pyrolysis Products from Polyethylene |

|

Table 7 Aliphatic and Aromatic Hydrocarbon Content in the Pyrolysis Oils of the Waste PE Unit (Area%) |

The waste PE underwent pyrolysis in a fixed bed reactor to recover waxy oil, and their characteristics were investigated. Initially, at a pyrolysis temperature of 460 ℃ and a nitrogen flow rate of 2 L/min, the waxy oil maximum yield was approximately 71.1 wt% without catalysts. When using A4 zeolite, the maximum yield of waxy oil was 76.4 wt%. The ratio of waxes with a carbon number of C19 and above reached a maximum yield of around 41.7 wt%. In the GC/MS analysis, the components of waxy oil obtained from A4 zeolite mainly comprised alkene groups, such as decene and cetene. In contrast, the waxy oil components from Beta and Y zeolites mainly consisted of aromatic olefin groups, such as benzene, naphthalene, and nonene. When ZSM-5 was used, the waxy oil mostly comprised aromatic groups like benzene, toluene, and xylene (BTX), naphthalene, and mesitylene. When the A4 zeolite catalyst was applied, the soft wax (C19-C23) was produced with a maximum yield of 71.2%, which can positively contribute to the production of lubricant base oils. In the SIMDIS analysis, the waxy oil produced from pyrolysis from waste PE mainly generated compounds with high boiling points as the pyrolysis reaction temperature increased. Therefore, the waxy oil with A4 zeolite is more effective than non-catalytic pyrolysis in converting normal paraffin (C8 and C26-C34) into non-normal paraffin. Also, the non-normal paraffin had a maximum distribution of 92%. The waxes rich in branched paraffin (non-normal paraffin) can serve as a chemical platform, facilitating their recycling into virgin-grade polymers for reproducibility or reuse in various applications, such as lubricating materials. Depending on the calcination conditions of A type zeolites, the pyrolysis reaction path of PE shows a unique characteristic that changes significantly. This suggests that the catalyst and pretreatment conditions can be precisely controlled to obtain a desired hydrocarbon distribution. In the following experiment, we will experiment on the influence of controlling the hydrocarbon range of waste PE pyrolysis wax by using zeolites with various A types and calcination conditions as variables.

- 1. Kibria, M. G.; Masuk, N. I.; Safayet, R.; Nguyen, H. Q.; Mourshed M. Plastic Waste: Challenges and Opportunities to Mitigate Pollution and Effective Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 17, 20.

-

- 2. Kumar, R.; Verma, A.; Shome, A.; Sinha, R.; Sinha, S.; Jha, P.K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, P.; Shubham; Das, S.; Sharma, P. Impacts of Plastic Pollution on Ecosystem Services, Sustainable Development Goals, and Need to Focus on Circular Economy and Policy Interventions. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 9963.

-

- 3. Geyer, R. Production, Use, and Fate of Synthetic Polymers, Academic Press: Cambridge, 2020.

- 4. R. Geyer, J. R. Jambeck, K. L. Law, Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782.

-

- 5. Evode, N.; Qamar, S.A.; Bilal, M.; Barceló, D.; Iqbal, H. M. N. Evaluation of Emerging Pollutants in Environmental Engineering. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100142.

- 6. Al-Fatesh, A. S.; Al-Garadi, N. Y. A.; Osman, A. I.; Al-Mubaddel, F. S.; Ibrahim, A. A.; Khan, W. U.; Alanazi, Y. M.; Alrashed, M. M.; Alothman, O. Y. From Plastic Waste Pyrolysis to Fuel: Impact of Process Parameters and Material Selection on Hydrogen Production. Fuel, 2023, 344, 128107.

-

- 7. Yang, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Msigwa, G.; Osman, A. I.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D. W.; Yap, P. S. Circular Economy Strategies for Combating Climate Change and Other Environmental Issues. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 55-80.

-

- 8. Alhazmi, H.; Almansour, F. H.; Aldhafeeri, Z. Plastic Waste Management: A Review of Existing Life Cycle Assessment Studies. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 5340.

-

- 9. Walendziewski, J. Continuous Flow Cracking of Waste Plastics. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86 1265-1278.

-

- 10. Orozco, S.; Lopez, G.; Suarez, M. A.; Artetxe, M.; Alvarez, J.; Bilbao, J.; Olazar, M. Analysis of Hydrogen Production Potential from Waste Plastics by Pyrolysis and in Line Oxidative Steam Reforming. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 225, 107044.

-

- 11. Abbas-Abadi, M. S.; Ureel, Y.; Eschenbacher, A.; Vermeire, F. H.; Varghese, R. J.; Oenema, J.; Stefanidis, G. D.; Van Geem, K. M. Challenges and Opportunities of Light Olefin Production via Thermal and Catalytic Pyrolysis of End-of-life Polyolefins: Towards Full Recyclability. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 96, 101046.

-

- 12. Russell, J. M.; Gracida-Alvarez, U. R.; Winjobi, O.; Shonnard, D. R. Update to “Effect of Temperature and Vapor Residence Time on the Micropyrolysis Products of Waste High Density Polyethylene. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 10716-10719.

-

- 13. Tran, X. T.; Kim, E. S.; Mun, D. H.; Jung, T.; Shin, J.; Kang, N. Y.; Park, Y.-K.; Kim, D. K. Catalytic Cracking of Crude Waste Plastic Pyrolysis Oil for Enhanced Light Olefin Production in a Pilot-Scale Circulating Fluidized Bed Reactor. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 12493-12503.

-

- 14. Abdy, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Artamendi, I.; Allen, B. Pyrolysis of Polyolefin Plastic Waste and Potential Applications in Asphalt Road Construction: A Technical Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106213.

-

- 15. Hussain, I.; Ganiyu, S. A.; Alasiri, H.; Alhooshani, K. A State-ofthe-art Review on Waste Plastics-derived Aviation Fuel: Unveiling the Heterogeneous Catalytic Systems and Techno-economy Feasibility of Catalytic Pyrolysis. Energy Convers. Manage. 2022, 274, 116433.

-

- 16. Papari, S.; Bamdad, H.; Berruti, F. Pyrolytic Conversion of Plastic Waste to Value-Added Products and Fuels: A Review. Materials, 2021, 14, 2586.

-

- 17. Al-Salem, S. M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Leeke, G. A. Pyro-Oil and Wax Recovery from Reclaimed Plastic Waste in a Continuous Auger Pyrolysis Reactor. Energies, 2020, 13, 2040.

-

- 18. Mohanty, A.; Ajmera, S.; Chinnam, S.; Kumar, V. Pyrolysis of Waste Oils for Biofuel Production: An Economic and Life Cycle Assessment. Fuel Commun. 2024, 18, 100108.

-

- 19. Murti, Z.; Sinaga, R. Y. H.; Mulyono, M.; Otivriyanti, G.; Steven, S.; Wardani, M. L. D.; Laili, N. S. S.; Yustisia A.; Soekotjo, E. S. A.; Lukitari, V.; Sudiono, M.; Soedarsono, A.; Dewanti, D. How Important is the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Study of Plastic Waste? Use of Bibliometric Analysis to Reveal Research Positions and Future Directions. J. Teknol. Lingkungan, 2024, 25, 10-19.

-

- 20. Didier P. Recycled Polymers: Eco-Design, Structure/Property Relationships and Compatibility, MDPI book: Basel, 2024.

-

- 21. Valizadeh, S.; Valizadeh, B.; Seo, M. W.; Choi, Y. J.; Lee, J.; Chen, W. H. Recent Advances in Liquid Fuel Production from Plastic Waste via Pyrolysis: Emphasis on Polyolefins and Polystyrene. Environ. Res. 2024, 246, 118154.

-

- 22. Liu, L.; Barlaz, M. A.; Johnson, J. X. Johnson, Economic and Environmental Comparison of Emerging Plastic Waste Management Technologies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107531.

-

- 23. Maniscalco, M.; Paglia, F. L.; Iannotta P.; Caputo, G.; Scargiali, F.; Grisafi, F.; Brucato, A. Slow pyrolysis of an LDPE/PP mixture: Kinetics and process performance. J. Energy Inst. 2021, 96, 234-241.

-

- 24. Al-Salem, S. M.; Dutta, A. Wax Recovery from the Pyrolysis of Virgin and Waste Plastics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 8301-8309.

-

- 25. Saeaung K.; Phusunti, N.; Phetwarotai, W.; Assabumrungrat, S.; Cheirsilp, B. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Petroleum-based and Biodegradable Plastic Waste to Obtain High-value Chemicals. Waste Manag. 2021, 127, 101-111.

-

- 26. Kremer, I.; Tomić, T.; Katančić, Z.; Erceg, M.; Papuga, S.; Vuković, J.P.; Schneider, D. R. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Mechanically Non-recyclable Waste Plastics Mixture: Kinetics and Pyrolysis in Laboratory-scale Reactor. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 296, 113145.

-

- 27. Wang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Gu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, H. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyethylene for the Selective Production of Monocyclic Aromatics over the Zinc-Loaded ZSM-5 Catalyst. ACS Omega, 2022, 7, 2752-2765.

-

- 28. Neuner, P.; Graf, D.; Netsch, N.; Zeller M.; Herrmann T.-C.; Stapf D.; Rauch, R. Chemical Conversion of Fischer–Tropsch Waxes and Plastic Waste Pyrolysis Condensate to Lubricating Oil and Potential Steam Cracker Feedstocks. Reactions, 2022, 3, 352-373.

-

- 29. Vieira de Souza, C.; Corrêa, S. M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Diesel Emission. Diesel Fuel and Lubricant Oil. Fuel, 2016, 185, 925-931.

-

- 30. Abidin M. R. S. Z.; Noh, M. H.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Goto M. Evaluation of Crude Oil Wax Dissolution Using a HydrocarbonBased Solvent in the Presence of Ionic Liquid. Processes 2023, 11, 1112.

-

- 31. Chaudhari, U. S.; Kulas, D. G.; Umlor, L.; Cronan, A.; Peralta, A.; Hossain, T.; Handler, R. M.; Johnson, A. T.; Reck, B. K.; Thompson, V. S.; Hartley, D. S.; Watkins, D. W.; Shonnard, D. R. Liquid Fed Pyrolysis of Polyethylene Films: Environmental and Economic Assessments of Co-located and Remotely-Located U.S. Facilities. ACS Sustainable Resour. Manage. 2024, 11, 1112.

-

- 32. Sarker, M.; Rashid, M. M.; Molla, M.; Rahman, M. S. Un-ProportionalMunicipal Waste Plastic Conversion into Fuel Using Activated Carbon and HZSM-5 Catalyst. J. Appl. Chem. Sci. 2012, 4, 1-8.

- 33. Vellaiyan, S. Aljohani, K.; Aljohani, B. S.; Reddy, B. R. S. R. Enhancing Waste-derived Biodiesel Yield Using Recyclable Zinc Sulfide Nanocatalyst: Synthesis, Characterization, and Process Optimization. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102411.

-

- 34. Al-Asadi, M.; Miskolczi, N.; Eller, Z. Pyrolysis-gasification of Wastes Plastics for Syngas Production Using Metal Modified Zeolite Catalysts Under Different Ratio of Nitrogen/oxygen. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 102411.

-

- 35. Vaishnavi, M.; Vasanth, P. M.; Rajkumar, S.; Gopinath, K. P.; Devarajan, Y. A Critical Review of the Correlative Effect of Process Parameters on Pyrolysis of Plastic Wastes. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis, 2023, 170, 105907.

-

- 36. Kusenberg, M.; Zayoud, A.; Roosen M.; Thi, H. D.; Abbas-Abadi, M. S.; Eschenbacher, A.; Kresovic, U.; Meester, S. D.; Geem, K. M. V. A Comprehensive Experimental Investigation of Plastic Waste Pyrolysis Oil Quality and its Dependence on the Plastic Waste Composition. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 277, 107090.

-

- 37. Qiu, L.; Murashov, V.; White, M. A. Zeolite 4A: Heat Capacity and Thermodynamic Properties. Solid State Sci. 2000, 2, 841-846.

-

- 38. Zasypalov, G. O.; Klimovsky, V. A.; Abramov, E. S.; Brindukova, E. E.; Stytsenko, V. D.; Glotov, A. P. Hydrotreating of Lignocellulosic Bio-Oil (A Review). Petrol. Chem. 2024, 63 1143-1169.

-

- 39. Beltrão-Nunes, A.-P.; Pires, M.; Roy, R.; Azzouz, A. Surface Basicity and Hydrophilic Character of Coal Ash-Derived Zeolite NaP1 Modified by Fatty Acids. Molecules, 2024, 29, 768.

-

- 40. Moghaddam, A. L.; Ghavipour, M.; Kopyscinski, J.; Hazlett M. J. Methanol Dehydration to Dimethyl Ether over KFI Zeolites. Effect of Template Concentration and Crystallization Time on Catalyst Properties and Activity. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2024, 672, 119594.

-

- 41. Netsch, N.; Vogt, J.; Richter, F.; Straczewski, G.; Mannebach, G.; Fraaije, V.; Mihan, S.; Stapf, I. D.; Tavakkol, S. Chemical Recycling of Polyolefinic Waste to Light Olefins by Catalytic Pyrolysis. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2023, 95, 1305-1313.

-

- 42. Mastral, F. J.; Esperanza, E.; Garcia, P.; Juste, M. Pyrolysis of High-density Polyethylene in a Fluidised Bed Reactor. Influence of the Temperature and Residence Time. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2002, 63, 1-15.

-

- 43. Kassargy, C.; Awad, S.; Burnens, G.; Kahine, K.; Tazerout, M. Experimental Study of Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyethylene and Polypropylene over USY Zeolite and Separation to Gasoline and Diesel-like Fuels. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 127, 31-37.

-

- 44. Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Gholizadeh, M.; Hu, X. Different Reaction Behaviours of Light or Heavy Density Polyethylene During the Pyrolysis with Biochar as the Catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 399, 123075.

-

- 45. Rodríguez-Luna, L.; Bustos-Martínez, D.; Valenzuela, E. TwoStep Pyrolysis for Waste HDPE Valorization. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 149, 526-536.

-

- 46. Santos, E.; Rijo, B.; Lemos, F.; Lemos, M. A. A Catalytic Reactive Distillation Approach to High Density Polyethylene Pyrolysis - Part 2 - Middle Olefin Production. Catalysis Today, 2021, 379, 212-221.

-

- 47. Matar, S.; Hatch, L. F. Chemistry of Petrochemical Processes, Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, 2001.

- 48. Dry, M. E. Sasol’s Fischer-Tropsch Experience. Hydrocarbon Processing, 1982, 61, 121.

- 49. Zacharopoulou, V.; Lemonidou A. A. Olefins from Biomass Intermediates: A Review. Catalysts, 2018, 8, 2.

- 50. Gray, M. R.; McCaffrey, W. C. Role of Chain Reactions and Olefin Formation in Cracking, Hydroconversion, and Coking of Petroleum and Bitumen Fractions. Energy & Fuels 2002, 16, 756-766.

-

- 51. Singh, O.; Khairun, H. S.; Joshi, H.; Sarkar, B.; Gupta, N. K. Advancing Light Olefin Production: Exploring Pathways, Catalyst Development, and Future Prospects. Fuel, 2024, 379, 132992.

-

- 52. Sonawane, Y. B.; Shindikar, M. R.; Khaladkar, M. Y. Effect of Fly Ash in Pyrolysis of HDPE, LDPE, and PP Plastic Waste. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2024, 23, 1735-1742.

-

- 53. G. Ali Mansoori, H. Lindsey Barnes, Glenn M. Webster. Chapter 4: Petroleum Waxes, In Fuels and Lubricants Handbook: Technology, Properties, Performance, and Testing, Totten, G. E. Shah, R. J., Forester, D. R., Eds.; ASTM International: West Conshohcken, 2019; pp 79-113.

-

- 54. Freund, M.; Csikós, R.; Keszthelyi, S.; Mózes, G. Paraffin Products: Properties, Technologies, Applications. Developments in Petroleum Series. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1982.

- 55. Scaffaro, R.; Mantia, F.; Botta, L.; Morreale, M.; Dintcheva, N.; Mariani, P. Competition Between Chain Scission and Branching Formation in the Processing of High-Density Polyethylene: Effect of Processing Parameters and of Stabilizers. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2009, 49, 1316-1325.

-

- 56. Zou, L.; Xu, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, M. Chemical Recycling of Polyolefins: A Closed-Loop Cycle of Waste to Olefins. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad207.

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 49(5): 579-593

Published online Sep 25, 2025

- 10.7317/pk.2025.49.5.579

- Received on Feb 7, 2025

- Revised on Mar 25, 2025

- Accepted on Apr 14, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

- Supporting Information

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Soo-Hwa Jeong

-

Korea Institute of Industrial Technology (KITECH), 89 Yangdaegiro-gil, Ipjang-myeon, Seobuk-gu, Cheonan-si 31056, Korea

- E-mail: pysoo80@kitech.re.kr

- ORCID:

0000-0002-3524-9979

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.