- Influence of Rheological Properties on the Structural and Mechanical Characteristics of Pitch-Based Carbon Fibers

Byungwook Youn, Yangyul Ju, Hae Reum Shin*, Kwang Youn Cho*,†

, Man Tae Kim*,†

, Man Tae Kim*,†  , and Doo Jin Lee†

, and Doo Jin Lee†

Department of Polymer Science and Engineering, Chonnam National University, 77 Yongbong-ro, Gwangju 61186, Korea

*Aerospace&Defense R&D Group, Korea Institute of Ceramic Engineering and Technology, 101 Soho-ro, Jinju 52851, Korea- 피치계 탄소섬유의 유변학적 거동과 섬유의 구조적 및 기계적 특성 상관관계 분석

전남대학교 고분자공학과, *한국세라믹기술원 항공복합소재센터

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

Activated pitch-based carbon fiber is typically produced through four sequential processes, including melt-spinning, oxidation, pre-carbonization, and activation. During heat treatment, the pitch-based fiber gradually transforms into a graphene-like structure, which enhances thermal stability and mechanical strength. Additionally, activation modifies the dense structure into a highly porous carbon fiber. In this study, the viscoelasticity of pitch melts is identified as a critical factor that influences not only the mechanical properties and porosity of the final carbon fiber but also its melt-spinnability. Under optimal melt-spinnability conditions, fibers spun from high-viscosity pitch exhibit stronger interactions between carbon atoms and oxygen functional groups during oxidation. This interaction leads to increases of 35% in tensile strength and 24% in elastic modulus. However, the excessive release of oxygen-carbon bonds during carbonization results in reduced mechanical strength and specific surface area. These findings highlight the significant role of melt viscoelasticity in determining the physical properties of carbon fibers. Furthermore, rheological analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of the overall carbon fiber preparation process.

활성화 피치 탄소섬유는 일반적으로 용융방사, 산화, 탄화, 활성화 공정의 네 단계를 통해 제조된다. 피치 섬유는 산화 및 탄화 공정을 통해 그래핀과 같은 구조로 전환되어 우수한 열안정성과 기계적 성질을 갖는다. 또한, 활성화 공정은 밀도가 높은 탄소섬유를 밀도가 낮은 다공성 구조로 변형시킨다. 이 연구에서는 피치 용융물의 점탄성과 용융방사의 상관 관계를 파악하였고, 피치의 점탄성이 탄소 섬유의 기계적 특성과 다공성에도 영향을 주는 것을 분석하였다. 상대적으로 높은 점탄성을 가진 피치계 용융물은 섬유 방사성이 더 우수하였고, 산화 과정에서 탄소 원자들과 산소 작용기 간의 상호작용으로 인해 인장강도는 35%, 탄성계수는 24% 증가하였다. 이후 탄화 및 활성화 과정에서 탄소와 산소 간 결합이 제거되어 기계적 강도와 비표면적이 감소하였다. 용융 방사물의 점탄성 분석은 탄소 섬유의 기계적 특성 및 탄화된 섬유의 기공 특성, 섬유 제조 공정을 최적화하는데 유용하다고 판단한다.

The viscoelasticity of pitch melts plays a crucial role in determining the melt-spinnability, mechanical properties, and porosity of activated pitch-based carbon fibers. Higher viscoelasticity enhances fiber formation, oxidation-induced strength, and elasticity but leads to structural collapse during carbonization, affecting mechanical strength and surface area. Rheological analysis provides key insights into optimizing carbon fiber fabrication.

Keywords: pitch, carbon fiber, rheological characterization, melt-spinnability, oxidation, activation.

This work was partly supported by Korea Research Institute for defense Technology planning and advancement (KRIT) grant funded by the Korea government (Defense Acquisition Program Administration) (KRIT-CT-23-039, Manufacturing of Asymmetric Ultra-High Temperature Ceramic Composites Leading edge with carbon fiber derived from Pitch) and by Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2024-00402807).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Carbon fibers are widely used in various industries, including energy, automotive, aerospace, military, and sports, due to their high tensile strength, modulus, chemical resistance, and excellent thermal and electrical conductivity.1-3 These exceptional properties are closely related to the gradual heat treatment stages, specifically oxidation and carbonization, following the fabrication of the precursor. During oxidation, precursors undergo a controlled reaction in air at 200-300 ℃, leading to crosslinking between polymer chains through the introduction of oxygen atoms. Subsequent heat treatment above 800 ℃ in an inert atmosphere, known as carbonization, facilitates the formation of a graphitic-like structure, enhancing the fiber properties.2,4-6

The primary precursor materials for carbon fiber production are polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and pitch, which exhibit distinct characteristics depending on the spinning process and structural evolution during heat treatment.7 Pitch-based carbon fibers offer advantages over PAN-based fibers, including higher thermal conductivity, greater carbon yield, and lower production costs.8-11 Pitch precursors are fabricated through melt-spinning, where pitch powders are heated above the softening point in an inert atmosphere. The molten pitch is then extruded through a spinneret and rapidly cooled, forming micro-diameter fibers.12 However, the quality of melt-spun fibers is influenced by several parameters, including molecular weight, softening point, carbon yield, and quinoline insoluble content.13 Rheological behavior can provide an indicator for evaluation of melt-spinnability. Mobility and orientation of polymer chains along the spinneret have a relationship with the viscosity and viscoelastic properties of the melts, contributing to fiber diameter distribution and their mechanical properties.14,15 These various characteristics of the precursors alter the physical properties of the final carbon fibers.

In this study, pitch-based activated carbon fibers with different softening points were analyzed to investigate structural modifications and various physical properties throughout the melt-spinning, oxidation, carbonization, and activation processes. The melt-spinnability of pitch melts was evaluated based on their viscoelastic properties using rheological analysis. The viscoelasticity of the pitch melts significantly influenced not only the formation of melt-spun fibers but also the subsequent processing stages. Variations in viscoelasticity led to differences in the network structure and mechanical properties due to the bonding interactions between carbon and oxygen atoms. Furthermore, after carbonization, the degree of oxygen bond elimination contributed to variations in the mechanical strength and pore structure of the final carbon fibers.

Materials. Two types of isotropic pitch powders, E-P24 and P1, were purchased from Dongyang Environment Co. (Korea) for this study. These powders have different softening points, 220 ℃ for P1 and 240 ℃ for E-P24, while exhibiting an identical mean particle size of 185 μm and similar reaction yields of 57% for P1 and 56% for E-P24. Additionally, the two isotropic pitch powders were subjected to elemental component analysis in Table 1. Both samples contained identical elements (C, H, O, N, S) and had slight differences in contents between hydrogen and carbon. All materials were used as received without further purification.

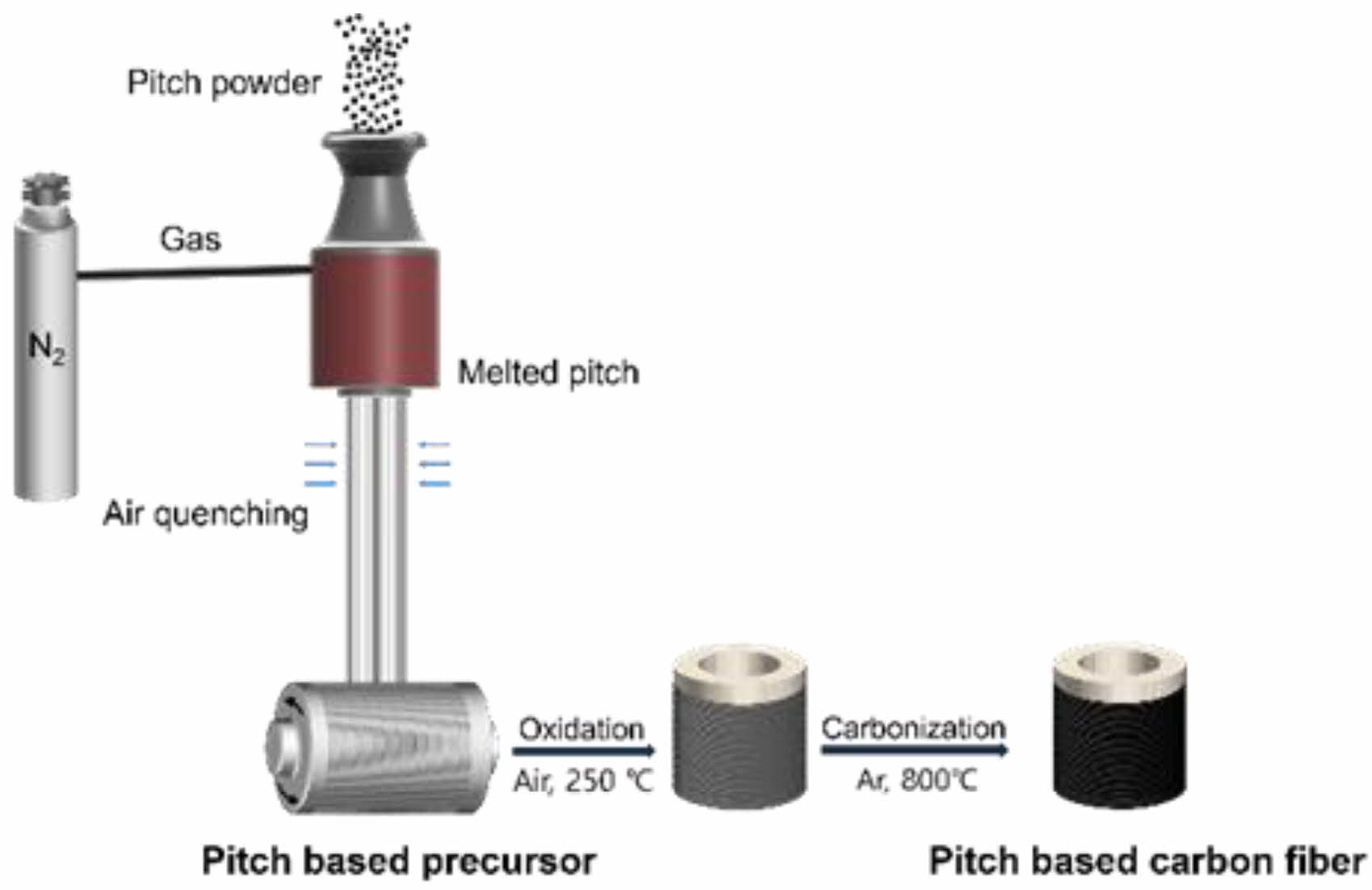

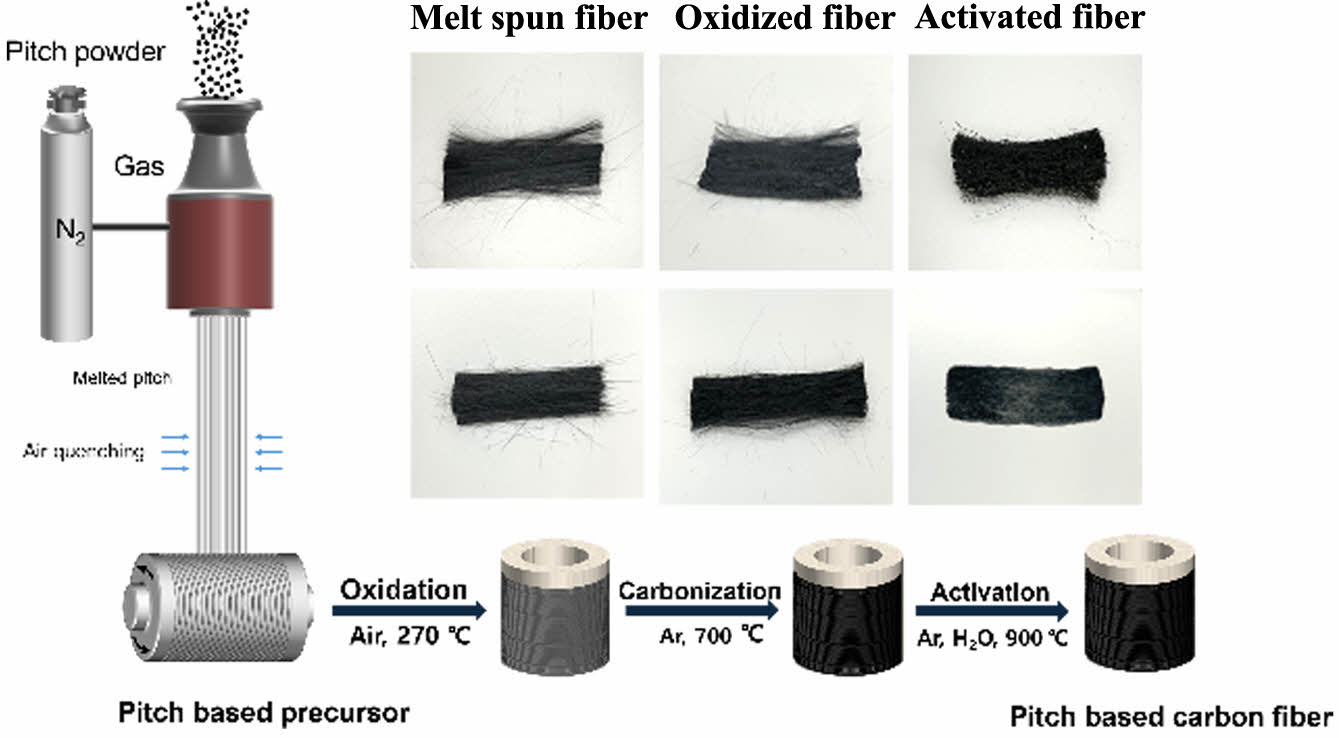

Preparation of Pitch-based Carbon Fibers. Figure 1 illustrates the preparation of pitch-based carbon fibers from melt-spun pitch precursors. During melt-spinning, appropriate temperatures were selected based on the softening points of the pitch to ensure the formation of a stable molten fluid without inducing structural reactions. The melt-spinning was performed at a higher temperature of 35 ℃ (P1: 255 ℃, E-P24: 275 ℃) than the softening point, respectively. The melts were extruded through a multi-spinneret with a diameter of 0.75 mm under a pressure range of 0.01-0.05 MPa, gradually cooled in the ambient atmosphere, and collected using a fixed-speed winder operating at 350-380 rpm. Cooling in air and controlled winding facilitated the alignment of irregular pitch molecules, enhancing the mechanical properties of the pitch-based precursors. Following precursor fabrication, oxidation was performed in an air atmosphere at 270 ℃ for 2 h. Since pitch precursors are not crosslinked, they remain unstable upon heating.

Oxidation serves as an essential intermediate process that converts the precursors to a thermosetting state, preventing degradation during carbonization. This transformation occurs through modifications in the chemical structure via bonding between carbon and oxygen groups. After oxidation, carbonization was carried out in an inert argon atmosphere at 700 ℃ for 1 h. During this process, the pitch fibers became more compact as graphitic-like structures formed, facilitated by crosslinking and the removal of impurities, including nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, and low-molecular-weight pitch components. Finally, to induce pore formation, the fibers were heated to 900 ℃ in an argon atmosphere, followed by steam activation at a rate of 0.8 g/min.

Characterizations. The elemental components of the two pitch powders were detected by elemental component analysis (CS744 ON836, Leco, USA). The softening points of the two pitch powders were measured according to the ASTM D3104 standard, and the reaction yield was characterized by determining the glass transition temperature using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) with a STA 449 F3 (Jupiter, Germany). The chemical differences between melt-spun and oxidized fibers were analyzed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, L18601116, PerkinElmer, USA). Fiber morphology and micropore structures on the fiber surface were examined through field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JWM-7610F, JEOL Ltd., Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV. To evaluate the melt-spinnability of pitch melts based on their viscoelastic properties, a rheometer (MCR-502, Anton Paar, Austria) with a 25 mm plate-plate geometry was used above the softening point in a nitrogen atmosphere to prevent oxidation of the pitch powders. The specific surface area was determined using a Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analyzer (Tristar 3000, Micromeritics Co., USA) based on physical adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K.

|

Figure 1 Schematic illustration of the melt-spun and forming of activated carbon fibers. |

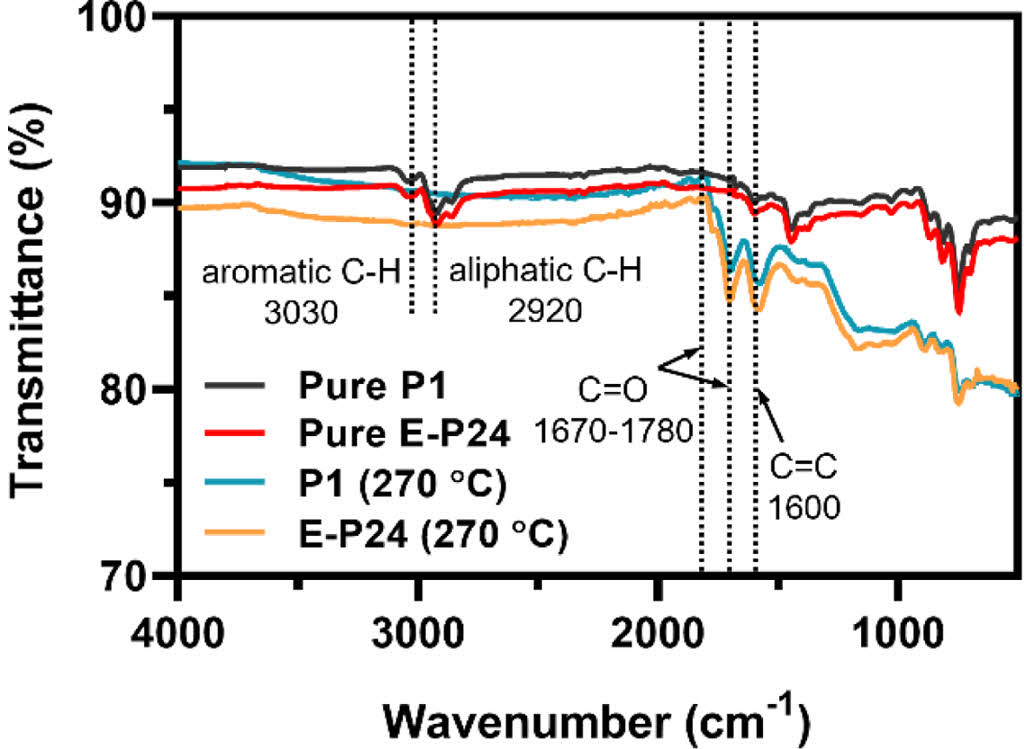

Chemical Structure. The chemical structure transformation of two types of pitch precursors in the oxidation is revealed via FTIR spectra in Figure 2. The two pitch precursors indicate common specific absorption peaks at 2920 cm-1 (aliphatic C-H stretching) and 3030 cm-1 (aromatic C-H stretching). On the other hand, the oxidized precursors generate novel specific peaks at 1670, 1680 cm-1 (C=O bonding), and 1600 cm-1 (aromatic C=C stretching with extinction of the aliphatic and aromatic C-H stretching peaks, attributing to the aforementioned introduction of oxygen atoms into carbon atoms of the pitch molecules and transformation into aromatic ring structures with dehydrogenation at 270 ℃. Besides, in both precursor and oxidized fiber, the peak intensity of E-P24 is higher than P1, which indirectly proves more oxidation reaction of the E-P24.16-18

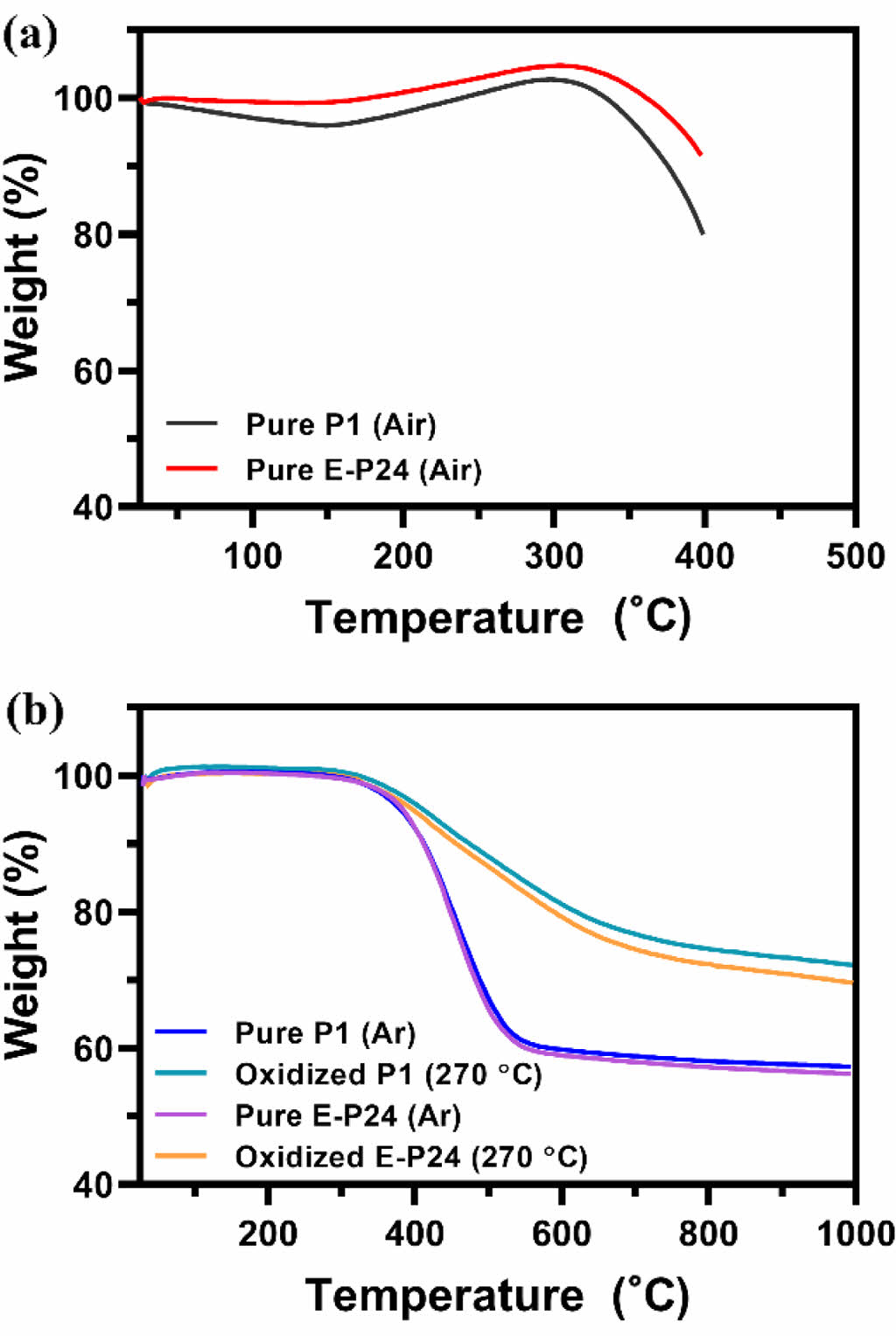

The TGA curve of the pitch precursors in the air atmosphere provides further evidence of a greater oxidation reaction response to the E-P24 precursor, as seen in Figure 3(a). Weight exceeding 100% of the pitch precursors in TGA analysis attributes to the introduction of oxygen-containing functional groups in air.17,19 These attachments of the oxygen functional groups in the E-P24 precursor are gained as of 182 ℃ contrast to the P1 precursor from 242 ℃. The weight increment of the E-P24 precursor (%) is higher than that of the P1 precursor, indicating an increase in oxidation reactions in E-P24. These oxidation reactions enhance thermal stability, as evidenced by the TGA curve in a nitrogen atmosphere, shown in Figure 3(b). The weight reduction of both the melt-spun and oxidized precursors begins at approximately 400 ℃. However, the pure precursor exhibits a rapid weight decrease, retaining only 60% of its initial weight, whereas the oxidized precursor forms double bonds that improve heat resistance.11,20 Additionally, the oxidized E-P24 precursor exhibits slightly greater weight loss than the oxidized P1 precursor, which is attributed to the loss of more carbon-oxygen bonding groups during carbonization. As a result, the final carbonized yield of E-P24 is lower (55%) compared to that of the P1 precursor (60%).

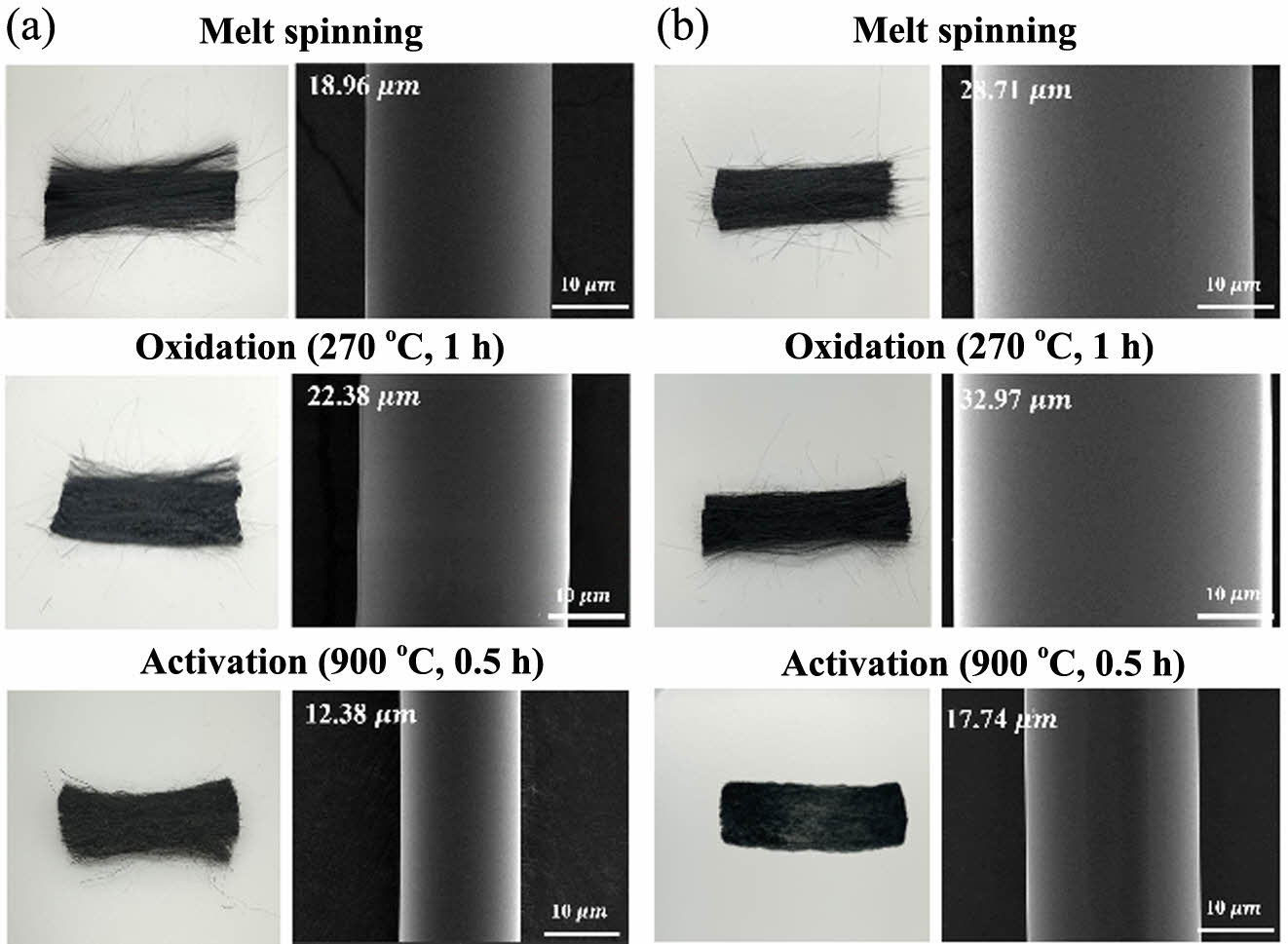

Morphology. As shown in Figure 4, the morphology of the two types of pitch precursors, oxidized precursors, and activated carbon fibers was examined using optical and FE-SEM imaging. The optical images reveal that the fiber surfaces are difficult to distinguish, while the SEM images indicate that all fibers exhibit smooth surfaces. The oxidized precursors retain their fiber diameters compared to the original precursors, demonstrating heat resistance due to thermal oxidation reactions despite exposure to elevated temperatures. However, during carbonization, the fiber diameter decreases significantly as non-carbon atoms and impurities are eliminated in the form of gases, leading to a more compact and ordered graphitic-like structure. Additionally, the melt-spun, oxidized, and activated carbon fibers derived from E-P24 have fiber diameters approximately 40% larger than those from P1. This difference is attributed to variations in the melt spinnability of the two pitch fibers, which are influenced by the viscoelasticity of the molten pitch.

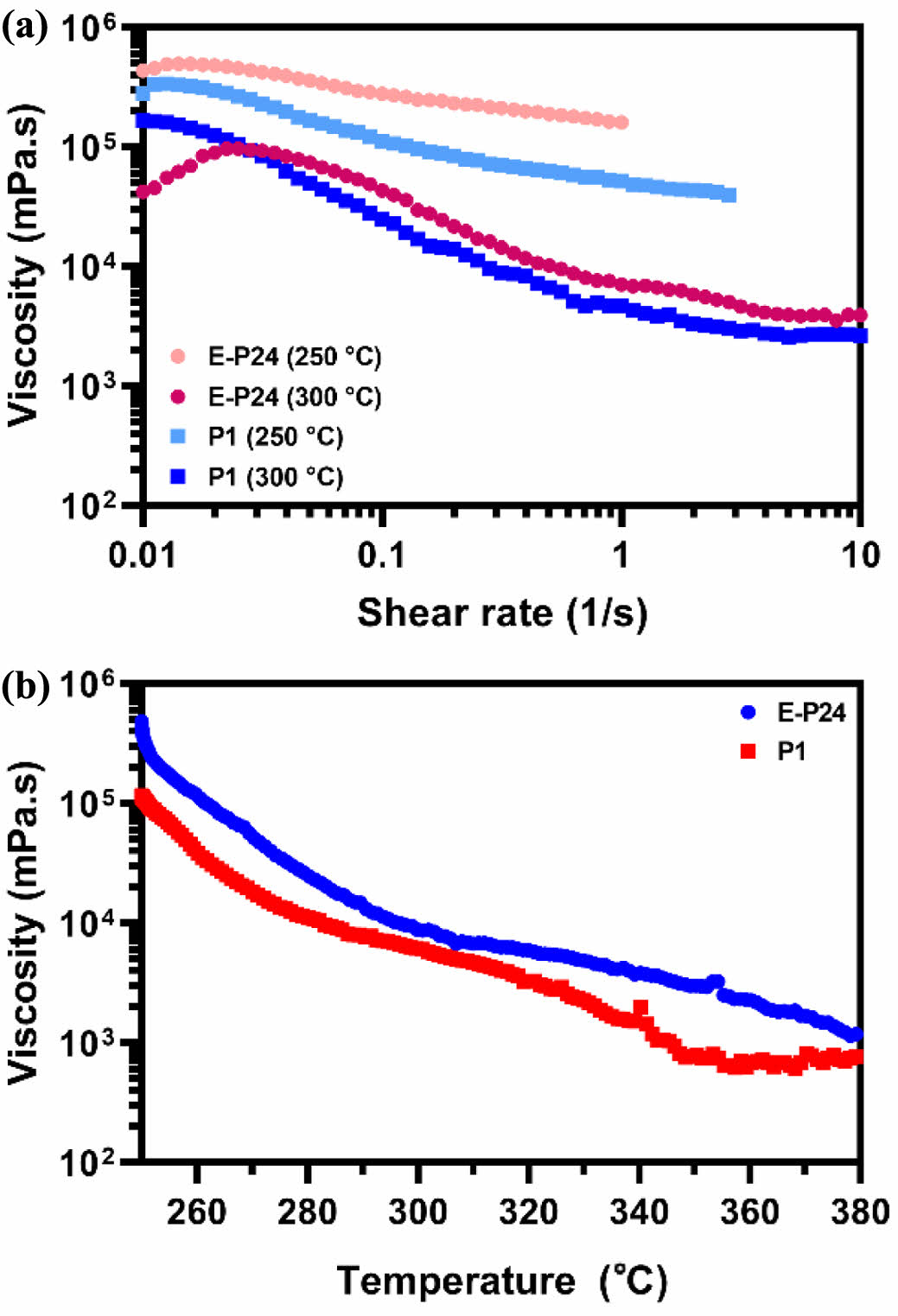

Rheological Property. The melt spinnability of each pitch-based fiber can be assessed through the viscoelastic characteristics of pitch melts using rheological analysis, as shown in Figure 5, 6. Figure 5(a) and 5(b) illustrate variations in the flow behavior of pitch melts as a function of shear rate and temperature. Each pitch melt exhibits shear-thinning behavior, where viscosity decreases with an increasing shear rate. Notably, as the temperature rises above the softening point, the reduction in viscosity becomes more pronounced. This shear-thinning behavior indicates the presence of physical entanglements between pitch chains. The E-P24 melts exhibit greater intermolecular entanglement compared to P1 melts, requiring higher shear stress to loosen chain entanglements.21,22

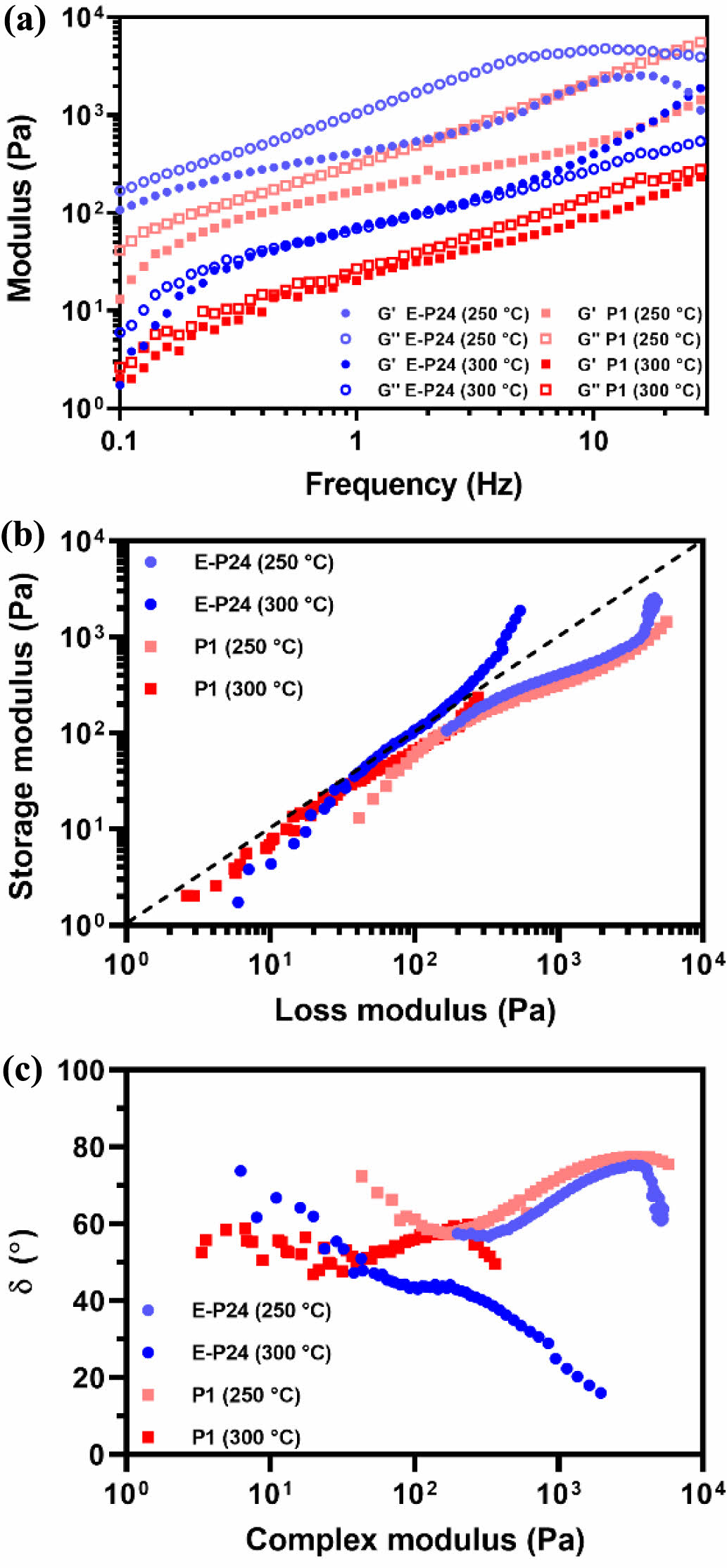

Figure 6(a) illustrates the relationship between storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G''), obtained through a frequency sweep at and above the softening point. At the softening point, all pitch melts exhibit distinct viscous behavior, characterized by G'' > G' across the entire frequency range. However, at 300℃, variations in G' behavior emerge, and a crossover point, where G' surpasses G'', appears in E-P24. The reciprocal of the frequency at this crossover point represents the relaxation time, which indicates the duration required for polymer chains to recover after external deformation.23 The E-P24 melts exhibit a short relaxation time of approximately 1 s, which is essential for ensuring smooth extrusion from the spinneret. This contributes to maintaining fiber integrity, achieving a higher fiber diameter, and ensuring consistent fiber diameter distribution. In contrast, although the P1 melt exhibits enhanced elastic behavior, its relaxation time is not well-defined, resulting in reduced fiber thickness and a broader fiber diameter distribution.24,25

Figure 6(b) further explains melt-spinnability through the slope between G' and G'', represented by the Cole-Cole plot. A linear slope approaching the G'=G'' line indicates a well-balanced relationship between viscosity and elasticity, which enhances fiber melt-spinnability.26 Therefore, increase from 250 ℃ to 300 ℃ is identified as a more suitable temperature for the melt-spinning of pitch. The E-P24 melts demonstrate superior melt-spinnability, as they more closely approach the G'=G'' line compared to the P1 melts.14,26,27

Since an increase in elastic behavior with rising temperature is uncommon, the viscoelastic behavior of pitch melts was further analyzed using the Van Gurp-Palmen plot, as shown in Figure 6(c). The complex modulus, defined as the sum of G' and G'', represents the overall resistance to deformation. Additionally, the phase angle (°) indicates the balance between elasticity and viscosity, with values above 45° signifying dominant viscous behavior and values below 45° indicating predominant elasticity.28,29 At 250 ℃, the complex modulus is higher, demonstrating significant resistance to deformation while viscous behavior remains dominant. This requires substantial force for the pitch melt to pass through the spinneret. Furthermore, the absence of a well-defined relaxation time delays the recovery of polymer chains, reducing melt-spinnability. In contrast, at 300 ℃, the complex modulus decreases, and elastic behavior becomes more pronounced, facilitating increased fiber diameter and enabling the pitch melts to pass through the spinneret with appropriate force. Notably, E-P24 exhibits a short relaxation time, allowing polymer chains to recover their structure more quickly, which contributes to a consistent fiber diameter distribution.24,30,31

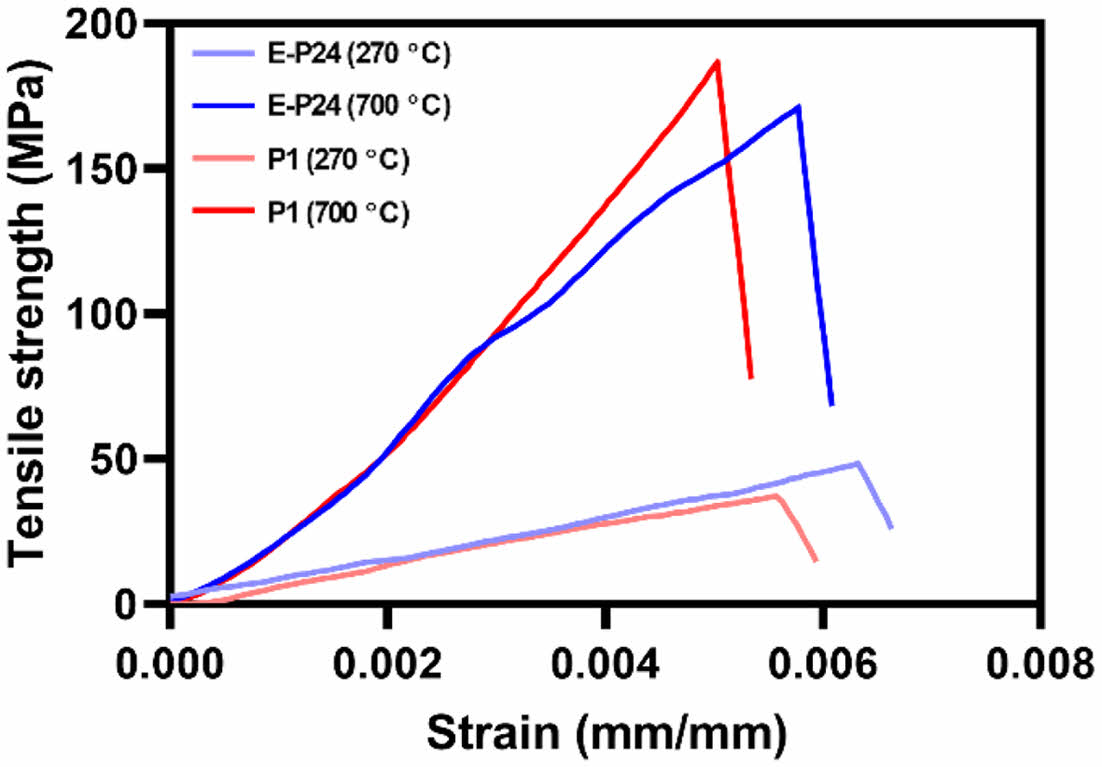

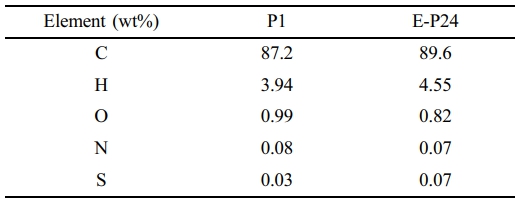

Mechanical Property. Figure 7 and Table 2 present the mechanical properties of oxidized precursors and carbonized fibers derived from E-P24 and P1. The oxidized E-P24 precursor exhibited higher elasticity due to a greater presence of oxygen functional groups after oxidation. The formation of a robust network structure between abundant carbon and oxygen atoms enhanced mechanical properties, resulting in higher tensile strength (48.5 MPa) and elongation at break (0.7%) compared to the P1 precursor, which exhibited a tensile strength of 36 MPa and elongation at break of 0.6%. However, during carbonization, the chemical structure of the pitch fiber transformed into a graphitic-like structure, with the removal of oxygen functional groups and other low-molecular-weight non-carbon species. The loss of strong carbon-oxygen bonds introduced structural defects in the carbon fiber, leading to an increase in tensile strength (170 MPa for E-P24 and 186.5 MPa for P1).18,21,32 Since the E-P24 precursor contained more oxygen bonding groups, it became denser during carbonization, which resulted in a reduction in mechanical strength.

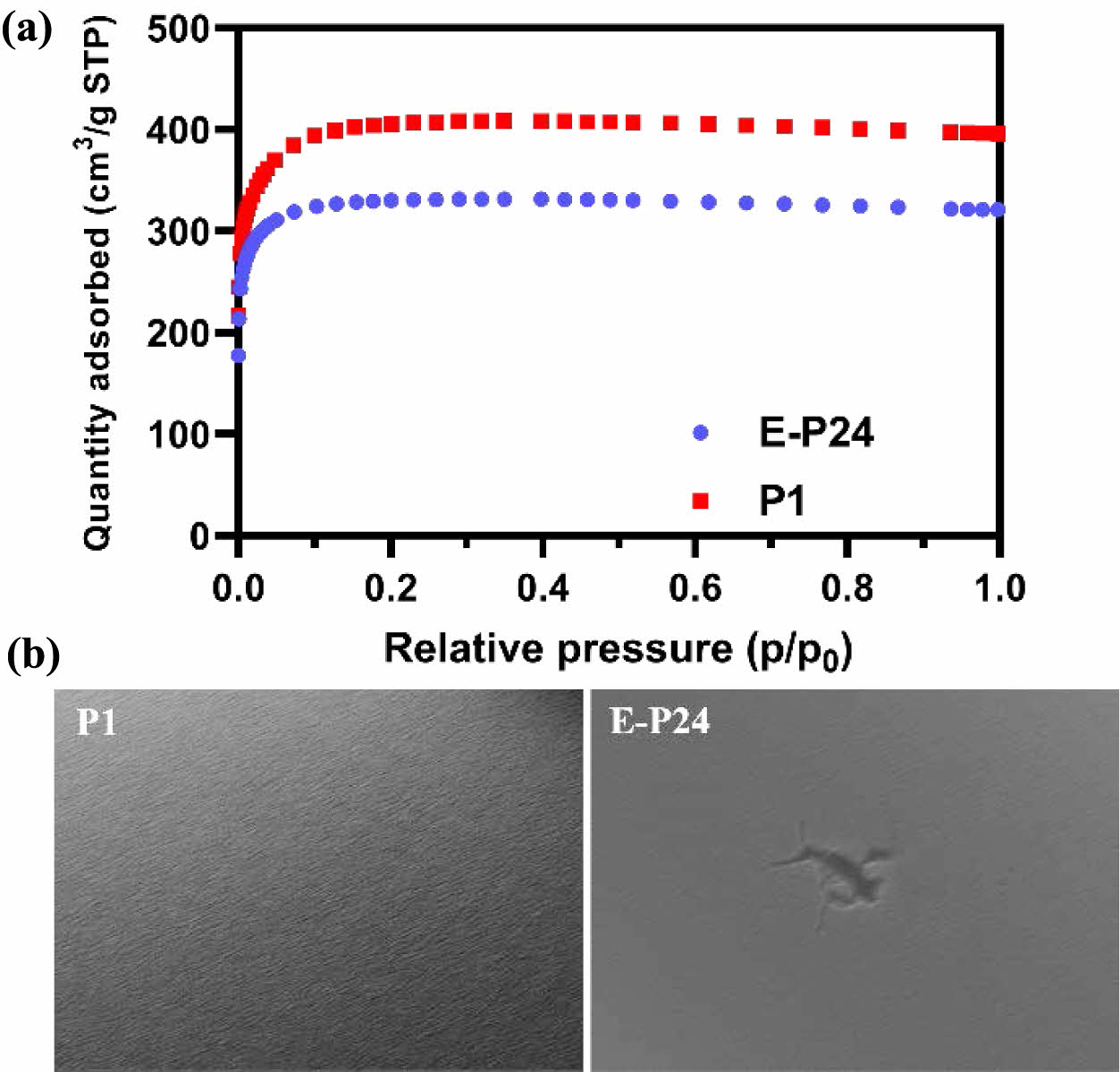

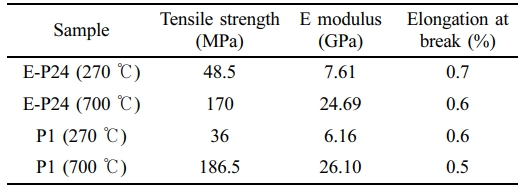

Porous Structure. The porous structure of the carbon fibers was analyzed using BET after the activation process, as seen in Figure 8(a). During activation, carbon fibers were exposed to high-temperature steam, which reacted with surface carbon molecules through gasification. This reaction generated CO and CO2 gases, leading to the formation of mesopores as gas evaporated from the surface.33,34 E-P24 carbon fibers exhibited more surface defects due to the removal of a higher quantity of oxygen functional groups, facilitating void formation in the activated carbon fiber. However, excessive oxygen functional groups can weaken the structural integrity of carbon fibers, potentially expanding micro- or mesopores due to structural collapse.34-36 Additionally, the thicker fiber diameter of E-P24 posed a challenge in ensuring uniform steam penetration, particularly within the interior of the fiber.37 As a result, the specific surface area of the activated E-P24 carbon fiber (1,325 m2/g) was lower than that of the activated P1 carbon fiber (1,598 m2/g). This pore formation mechanism was consistent with the surface morphology in Figure 8(b). The non-uniform mesopore is observed in the E-P24 activated carbon fiber in contrast to uniform micropore in the P1-based activated carbon fiber.

|

Figure 2 FTIR spectra of two types of melt-spun fibers and the oxidated precursor. |

|

Figure 3 TGA curves of two types of melt-spun fiber and precursors in different measuring conditions of atmosphere, temperature range, and heating rate: (a) Air, 25-400 ℃, 1 ℃/ min; (b) N2, 25- 1000 ℃, 10 ℃/min |

|

Figure 4 Optical images and SEM images of different types of melt-spun, oxidation, and activation carbon fibers: (a) P1; (b) E-P24. |

|

Figure 5 Viscosity as a function of different pitch powders: (a) shear rate was measured ranging from 0.01-10 s-1; (b) temperature sweep was analyzed from 250-380 ℃ at fixed shear rate of 0.1 s-1. |

|

Figure 6 (a) Dynamic frequency sweep of different pitch melts under a constant shear strain of 0.1% with ranging between 0.1-30 Hz; (b) Cole-Cole plot; (e) Van Gurp-Palmen plot of various pitch powders measured at different temperatures. |

|

Figure 7 Tensile properties of P1 and E-P24 fibers after oxidation at 270 ℃ and pre-carbonization at 700 ℃. |

|

Figure 8 N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm of different activated carbon fibers for quantifying the specific surface area. |

|

Table 2 Tensile Properties of P1 and E-P24 Fibers After Oxidation and Pre-carbonization |

In this study, two types of activated carbon fibers with different softening points were prepared through melt-spinning, oxidation, pre-carbonization, and activation processes. Rheological analysis demonstrated variations in viscosity and viscoelastic behavior, which influenced the melt-spinnability of the pitch melts. The E-P24 melt-spun fiber exhibited higher viscoelasticity, leading to improved melt-spinnability and a thicker mean fiber diameter with a narrower diameter distribution. During oxidation, the incorporation of a greater number of oxygen functional groups in E-P24 fibers contributed to enhanced mechanical strength compared to P1 fibers. However, the removal of excess oxygen bonds in the thicker fibers during carbonization resulted in structural collapse, leading to a reduction in mechanical strength and the formation of micro- and mesopores. These findings establish a connection between the rheological characteristics of pitch melts during melt-spinning and the physical properties of the final carbon fibers, providing valuable insight into the optimization of carbon fiber fabrication.

- 1. MInus, M.; Kumar, S. The Processing Properties, and Structure of Carbon Fibers. Jom 2005, 57, 52-58.

-

- 2. Frank, E.; Steudle, L. M.; Ingildeev, D.; Spörl, J. M.; Buchmeiser, M. R. Carbon Fibers: Precursor Systems, Processing, Structure, and Properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5262-5298.

-

- 3. Paiva, J. M. F. de; Santos, A. D. N. dos; Rezende, M. C. Mechanical and Morphological Characterizations of Carbon Fiber Fabric Reinforced Epoxy Composites Used in Aeronautical Field. Mat. Res. 2009, 12, 367-374.

-

- 4. Huang, X. Fabrication and Properties of Carbon Fibers. Materials 2009, 2, 2369-2403.

- 5. Newcomb, B. A. Processing, Structure, and Properties of Carbon Fibers. Compos. Ptart A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 91, 262-282.

- 6. Hameed, N.; Sharp, J.; Nunna, S.; Creighton, C.; Magniez, K.; Jyotishkumar, P.; Salim, N. V; Fox, B. Structural Transformation of Polyacrylonitrile Fibers During Stabilization and Low Temperature Carbonization. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2016, 128, 39-45.

-

- 7. Naito, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Yang, J.-M.; Kagawa, Y. Tensile Properties of Ultrahigh Strength PAN-based, Ultrahigh Modulus Pitch-based and High Ductility Pitch-based Carbon Fibers. Carbon 2008, 46, 189-195.

-

- 8. Jana, A.; Zhu, T.; Wang, Y.; Adams, J. J.; Kearney, L. T.; Naskar, A. K.; Grossman, J. C.; Ferralis, N. Atoms to Fibers: Identifying Novel Processing Methods in the Synthesis of Pitch-based Carbon Fibers. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn1905.

-

- 9. Naito, K.; Yang, J.-M.; Xu, Y.; Kagawa, Y. Enhancing the Thermal Conductivity of Polyacrylonitrile-and Pitch-based Carbon Fibers by Grafting Carbon Nanotubes on Them. Carbon 2010, 48, 1849-1857.

-

- 10. Kim, J.; Im, U.-S.; Lee, B.; Peck, D.-H.; Yoon, S.-H.; Jung, D.-H. Pitch-based Carbon Fibers From Coal Tar or Petroleum Residue Under the Same Processing Condition. Carbon Lett. 2016, 19, 72-78.

-

- 11. Shi, K.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Liu, H.; Yoon, S.-H.; Li, X. Effect of Oxygen-introduced Pitch Precursor on the Properties and Structure Evolution of Isotropic Pitch-based Fibers During Carbonization and Graphitization. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 199, 106291.

-

- 12. Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Liang, D.; Xie, Q. Development of Pitch-based Carbon Fibers: A Review. Energy Sources, Part A-Recovery, Util. Enviro. Eff. 2024, 46, 14492-14512.

-

- 13. Li, Q.; Zuo, P.; Qu, S.; Shen, W. Evolution of the Composition and Melting Behavior of Spinnable Pitch during Incubation. Molecules 2023, 28, 1097.

-

- 14. Lu, M.; Liao, J.; Gulgunje, P. V; Chang, H.; Arias-Monje, P. J.; Ramachandran, J.; Breedveld, V.; Kumar, S. Rheological Behavior and Fiber Spinning of Polyacrylonitrile (PAN)/Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Dispersions at High CNT Loading. Polymer 2021, 215, 123369.

-

- 15. Münstedt, H. Rheological Properties and Molecular Structure of Polymer Melts. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 2273-2283.

-

- 16. Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Balogun, M.-S.; Ouyang, T. J Controllable Pre-oxidation Strategy Toward Achieving High Compressive Strength in Self-bonded Carbon Fiber Monolith. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 1059-1070.

-

- 17. Kil, H.-S.; Jang, S. Y.; Ko, S.; Jeon, Y. P.; Kim, H.-C.; Joh, H.-I.; Lee, S. Effects of Stabilization Variables on Mechanical Properties of Isotropic Pitch Based Carbon Fibers. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 58, 349-356.

-

- 18. Niu, H.; Zuo, P.; Shen, W.; Qu, S. A Comprehensive Investigation on the Chemical Structure Character of Spinnable Pitch for Improving and Optimizing the Oxidative Stabilization of Coal Tar Pitch-based Fiber. Polymer 2021, 224, 123737.

-

- 19. Harrell, T. M.; Scherschel, A.; Love‐Baker, C.; Tucker, A.; Moskowitz, J. D.; Li, X. Influence of Oxygen Uptake on Pitch Carbon Fiber. Small 2023, 19, 2303527.

-

- 20. Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Shi, K.; Li, X. Effects of Oxygen Content of Pitch Precursors on the Porous Texture and Surface Chemistry of Pitch-based Activated Carbon Fibers. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 248.

-

- 21. Kim, B.-J.; Eom, Y.; Kato, O.; Miyawaki, J.; Kim, B. C.; Mochida, I.; Yoon, S.-H. Preparation of Carbon Fibers With Excellent Mechanical Properties From Isotropic Pitches. Carbon 2014, 77, 747-755.

-

- 22. Cato, A. D.; Edie, D. D. Flow Behavior of Mesophase Pitch. Carbon 2003, 41, 1411-1417.

-

- 23. Gold, B. J.; Hövelmann, C. H.; Lühmann, N.; Pyckhout-Hintzen, W.; Wischnewski, A.; Richter, D. The Microscopic Origin of the Rheology in Supramolecular Entangled Polymer Networks. J. Rheol. 2017, 61, 1211-1226.

-

- 24. Yoon, H.; Hinton, Z. R.; Heinzman, J.; Chase, C. E.; Gopinadhan, M.; Edmond, K. V; Ryan, D. J.; Smith, S. E.; Alvarez, N. J. The Effect of Pyrolysis on the Chemical, Thermal and Rheological Properties of Pitch. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 8925-8936.

-

- 25. Choi, J.; Lee, Y.; Chae, Y.; Kim, S.-S.; Kim, T.-H.; Lee, S. Unveiling the Transformation of Liquid Crystalline Domains Into Carbon Crystallites During Carbonization of Mesophase Pitch-derived Fibers. Carbon 2022, 199, 288-299.

-

- 26. Song, Y.; Joo, Y. J.; Ju, Y.; Youn, B.; Shin, D. G.; Cho, K. Y.; Lee, D. Polycrystalline Nanograin Formation in Uniform-sized Silicon Carbide Fibers Derived From Aluminum-containing Polycarbosilane. Fiber. Polym. 2023, 24, 3151-3161.

-

- 27. Rani, S.; Kumari, K.; Kumar, P.; Dhakate, S. R.; Kumari, S. Enhancing Spinnability and Properties of Carbon Fibers Through Modification of Isotropic Coal Tar Pitch Precursor. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 181, 106566.

-

- 28. Qian, Z.; McKenna, G. B. Expanding the Application of the Van Gurp-Palmen Plot: New Insights into Polymer Melt Rheology. Polymer 2018, 155, 208-217.

-

- 29. Trinkle, S.; Friedrich, C. Van Gurp-Palmen-plot: A Way to Characterize Polydispersity of Linear Polymers. Rheol. Acta 2001, 40, 322-328.

-

- 30. Ji, H. S.; Park, G.; Jung, H. W. Rheological Properties and Melt Spinning Application of Controlled-Rheology Polypropylenes via Pilot-Scale Reactive Extrusion. Polymers 2022, 14, 3226.

-

- 31. Nair, S. T.; Vijayan, P. P.; Xavier, P.; Bose, S.; George, S. C.; Thomas, S. Selective Localisation of Multi Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Polypropylene/natural Rubber Blends to Reduce the Percolation Threshold. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2015, 116, 9-17.

-

- 32. Karaaslan, M. A.; Gunning, D.; Huang, Z.; Ko, F.; Renneckar, S.; Abdin, Y. Carbon Fibers from Bitumen-derived Asphaltenes: Strategies for Optimizing Melt Spinnability and Improving Mechanical Properties. Carbon 2024, 228, 119300.

-

- 33. Banerjee, C.; Chandaliya, V. K.; Dash, P. S. Recent Advancement in Coal Tar Pitch-based Carbon Fiber Precursor Development and Fiber Manufacturing Process. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 158, 105272.

-

- 34. Lee, S. M.; Lee, S. H.; Jung, D.-H. Surface Oxidation of Petroleum Pitch to Improve Mesopore Ratio and Specific Surface Area of Activated Carbon. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 1460.

-

- 35. Kim, M. Il; Seo, S. W.; Kwak, C. H.; Cho, J. H.; Im, J. S. The Effect of Oxidation on the Physical Activation of Pitch: Crystal Structure of Carbonized Pitch and Textural Properties of Activated Carbon After Pitch Oxidation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 267, 124591.

-

- 36. Lim, T. H.; Yeo, S. Y. Investigation of the Degradation of Pitch-based Carbon Fibers Properties Upon Insufficient or Excess Thermal Treatment. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 4733.

-

- 37. Kwon, W.; Jeong, E. Adsorptive Removal of Nerve Gas via Activated Carbon Fiber: Precursor and Fabric Structure Effects. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 323, 129651.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 49(5): 610-617

Published online Sep 25, 2025

- 10.7317/pk.2025.49.5.610

- Received on Mar 10, 2025

- Revised on Apr 22, 2025

- Accepted on Apr 22, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusion

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Kwang Youn Cho* , Man Tae Kim* , and Doo Jin Lee

-

Department of Polymer Science and Engineering, Chonnam National University, 77 Yongbong-ro, Gwangju 61186, Korea

*Aerospace&Defense R&D Group, Korea Institute of Ceramic Engineering and Technology, 101 Soho-ro, Jinju 52851, Korea - E-mail: kycho@kicet.re.kr, ginggiscan@kicet.re.kr, dlee@chonnam.ac.kr

- ORCID:

0000-0002-4367-1408, 0000-0001-7939-4812, 0000-000

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.