- Effect of Co-pyrolysis of Waste Tires and Waste Plastics on the Distribution of Pyrolysis Products

Cangang Zhang*, **

, Lihua Xu***, Xinglong Ma*, and Weiquan Chen*,†

, Lihua Xu***, Xinglong Ma*, and Weiquan Chen*,†

*Dongying Vocational College of Science and Technology, No. 361, Yingbin Road, Guangrao County, Dongying City, Shandong Province, China, 257300, China

**City University Malaysia ,Menara City U, No. 8, Jalan 51A/223, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

***Hebei Vocational University of Technology and Engineering, No. 473, Quannan West Street, Xindu District, Xingtai City, Hebei Province, China, 054000, China- 폐타이어와 폐플라스틱의 공동 열분해가 열분해 생성물 분포에 미치는 영향

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

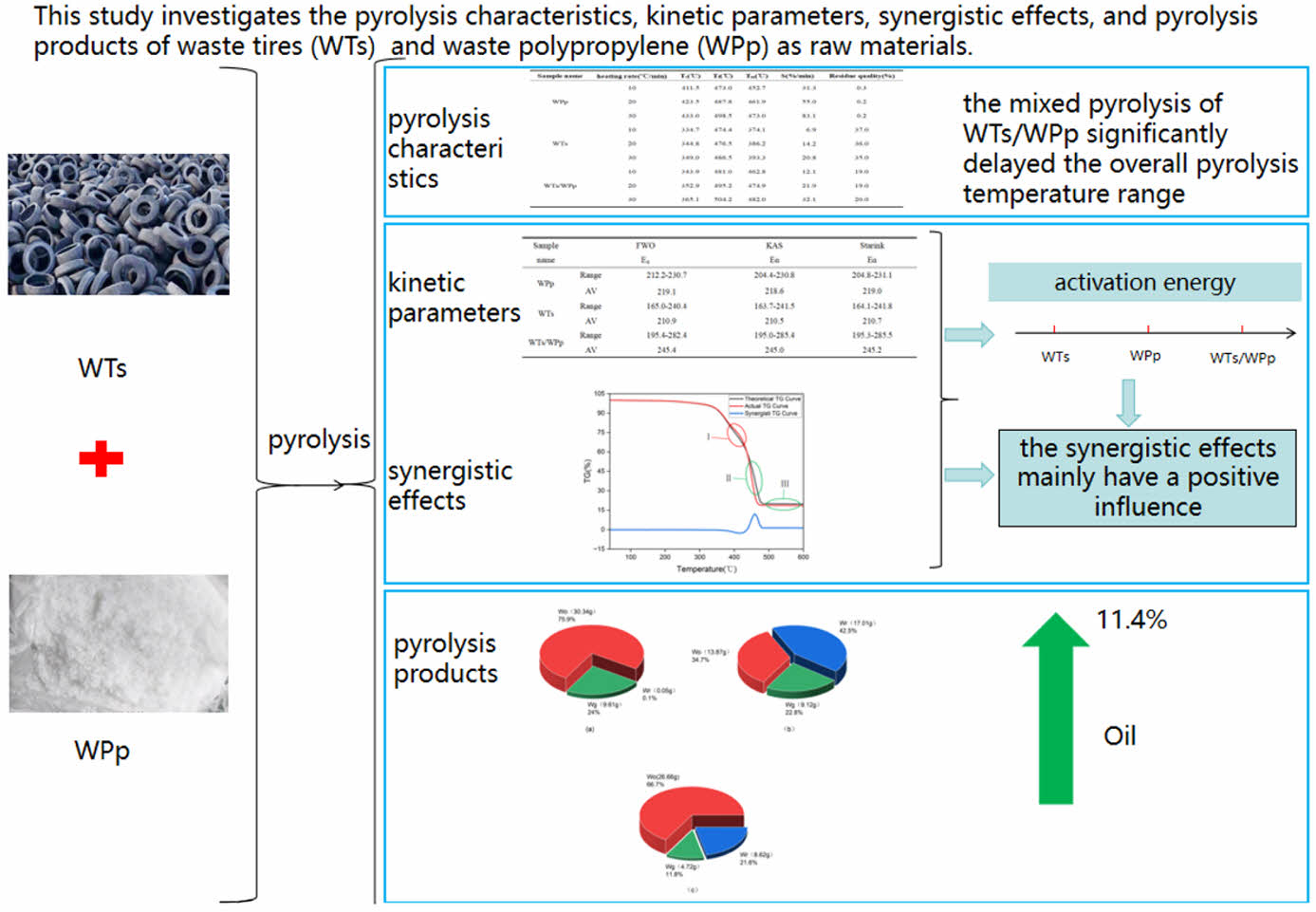

Among the most efficient and valuable methods for treating organic solid waste is pyrolysis technology. In this study, waste tires (WTs) and waste polypropylene (WPp) were selected as experimental materials, and their pyrolysis characteristics, kinetic parameters, synergistic effects and the pattern of pyrolysis product distribution were thoroughly investigated. In contrast to single-component WTs and WPp pyrolysis procedures, the mixed pyrolysis of WTs and WPp notably extended the overall temperature range for pyrolysis. This extension significantly facilitated the separation and recovery of the resulting pyrolysis products. Moreover, the elevation in the pyrolysis temperature range resulted in the mean value of activation energy for the mixed pyrolysis of WTs/WPp being greater than that associated with the individual pyrolysis of WTs and WPp .The synergistic effect analysis showed that the WTs/WPp co-pyrolysis process mainly showed positive synergistic effect. It showed that the improved distribution of pyrolysis products was a result of the combined pyrolysis of WTs and WPp. In contrast to single-component WT and WPp pyrolysis, the actual oil yield (66.7%) from the combined WTs/WPp pyrolysis exceeded the predicted oil yield (55.3%) by 11.4%. This arose from the positive synergistic effect of the mixed pyrolysis that promoted more pyrolysis gases to be converted into pyrolysis oil. The experimental and estimate findings mentioned above can serve as a theoretical guide and source of information for the industrial pyrolysis of WTs, WPp, and WTs/WPp.

It was shown that compared with the pyrolysis process of single-component waste tires (WTs) and waste polypropylene (WPp), the mixed pyrolysis of WTs/WPp significantly delayed the overall pyrolysis temperature range, which was helpful for the separation and recovery of pyrolysis products. The delayed pyrolysis temperature caused the average activation energy of the WTs/WPp mixed pyrolysis to be higher than that of the single component WTs,WPp. The synergistic effect analysis showed that the WTs/WPp co-pyrolysis process mainly showed positive synergistic effect, which indicated that the mixed pyrolysis of WTs/WPp contributed to the improvement of the distribution of pyrolysis products. Compared with the pyrolysis of single-component WPp and WTs, the actual oil yield (66.7%) of the mixed WTs/WPp pyrolysis was 11.4% higher than the theoretical oil yield (55.3%), which was attributed to the positive synergistic effect of the mixed pyrolysis that promoted more pyrolysis gases to be converted into pyrolysis oil.

Keywords: waste plastics, waste tires, pyrolysis properties, kinetics, synergies, pyrolysis products

The work was supported by Dongying Vocational College of Science and Technology, for which the authors would like to express their gratitude.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Waste tires (WTs), because of their distinct chemical and physical characteristics, including high abrasion resistance and difficult degradability, are highly susceptible to the formation of a new source of pollution-“black pollution”- if they are not properly treated. Meanwhile, as a potential recycling resource, the treatment of WTs is not only related to environmental protection, but also has a profound impact on economic benefits. The primary methods for disposing of waste tires are landfilling and incineration, but their drawbacks are significant. Landfilling poses environmental pollution risks and consumes large amounts of land resources, while incineration involves high operational costs and generates exhaust gases that cause secondary environmental pollution. Beyond these rudimentary disposal methods, there are more effective approaches such as recycling, tire retreading, rubber regeneration, and thermal energy utilization. Among these methods, pyrolysis is the ultimate treatment approach. Pyrolysis involves decomposing large organic molecules into smaller organic molecules, thereby producing various pyrolysis products. Pyrolysis offers advantages such as environmental friendliness, energy efficiency, high processing capacity, and significant resource recovery value, making it more aligned with the requirements for achieving environmental benefits and promoting a circular economy.1-4 In light of this context, tire pyrolysis has become a significant solution in the realm of organic solid waste management and energy production, owing to its environmentally friendly, efficient, and sustainable attributes. Numerous high-value products, including pyrolysis oil, carbon black, and pyrolysis gas, may be produced by pyrolyzing used tires. As a result, one of the most beneficial and promising treatment techniques now in use is the pyrolysis technology for waste tires.5-8

On the other hand, the production and consumption of plastic products have experienced unprecedented growth. According to statistics, the annual production of plastics has exceeded 360 million tons by 2018 and is expected to exceed 500 million tons by 2025,9 with polypropylene (PP), a fundamental component of packaging materials, being particularly ubiquitous. However, the short lifespan of these plastic products and the difficulty of natural degradation are gradually aggravating the problem of “white pollution”. This presents a significant risk to maritime environments, water resources, soil quality, and even biological health and other public health areas.10-13 Traditionally, the main methods of disposal of waste plastics have been recycling, incineration and landfill. However, globally, only 9% of waste plastics are recycled; 12% are incinerated and the remaining approximately 79% end up in landfills or in the natural environment.14 At the same time, the acidic gases released from the burning of waste plastics in the incineration process will inevitably corrode the equipment, and toxic gases such as dioxin will also be released, seriously jeopardizing human health. Landfill will cause extensive soil pollution and adversely affect land plants and aquatic environment. This “white pollution” will not only pollute the environment, but also cause a waste of resources.15 Consequently, developing efficient treatment strategies for waste plastics to mitigate the environmental burden has become an urgent and critical issue.16 Pyrolysis technology is regarded as an innovative way to break through the dilemma of resources and environment because it can efficiently transform waste plastics into high value-added oil and gas resources under anaerobic conditions, realizing the comprehensive goal of “reduction, harmlessness and resourcefulness”.17-18

Further, in response to the dual threats posed by “black pollution” and “white pollution”, researchers have initiated investigations into an innovative approach involving the mixed pyrolysis of waste tires alongside waste plastics. This technique uses the synergistic interactions between organic wastes to increase the production of pyrolysis products. Such a strategy not only maximizes the distribution of pyrolysis products but also achieves the goal of resolving waste concerns through waste recovery. As a result, this opens the door for more extensive uses of pyrolysis technology with regard to waste tires and waste plastics, indicating important opportunities for real-world application.19-20

The pyrolysis of tires was the focus of H. Zerin, M.G. Rasul, and M.I. Jahirul's investigation. They found that tires begin to pyrolyze at about 300 ℃ and finish decomposing at about 550 ℃. In their study, they compiled data from existing literature regarding the distribution of products resulting from tire pyrolysis, indicating that this process yields 30-65% oil, 25-45% carbon, and 5-20% gas.21 Conversely, Tariq Maqsood, Jinze Dai, Yaning Zhang, Mengmeng Guang, Bingxi Li, and their associates discovered that liquid oil is the primary byproduct of the pyrolysis of plastic trash, which can account for up to 90 wt%. Gas and carbon black are secondary products, contributing 3-90.2 wt% and 0.5-78 wt%, respectively. Interestingly, the liquid oil produced by pyrolyzing plastic waste has characteristics similar to those of conventional diesel.22 Additionally, a collaborative investigation by Najla Grioui, Kamel Halouani, Foster A. Agblevor, and others explored the co-pyrolysis of waste tires (WTs) and olive mill wastewater sludge (OMWS). Their detailed characterization of oil samples revealed a negative synergistic interaction between the two materials during the co-pyrolysis process.23 Meanwhile, researchers including Olga Sanahuja-Parejo, Alberto Veses, José Manuel López, Ramón Murillo, María Soledad Callón, and Tomás García have conducted extensive studies on the co-pyrolysis of WTs with grape seeds using a pilot-scale spiral reactor. Their comprehensive analysis of the solid, liquid, and gaseous products indicates that this approach significantly enhances the quality of the resulting bio-oil, which has considerable potential as a direct fuel source.24 Furthermore, F. Campuzano, C. F. Ortiz, M. Betancur, and J. D. Martínez et al. performed a chemical and thermochemical characterization of waste tires, rice hulls, and municipal solid waste.25 Additionally, Akash et al. and other researchers dynamically characterized the co-pyrolysis process involving hydrothermally treated Chlorella residue, polystyrene, and waste tires with regard to their pyrolysis behaviors, kinetics, interaction effects, As well to the characteristics of biochar, bio-oil, and in situ escaping gas. Their findings indicated that the temperature ranges for the decomposition of WTs and polystyrene spanned from 200 ℃ to 550 ℃ and from 300 ℃ to 550 ℃, respectively, with similar average activation energies for both materials. The study also demonstrated that co-pyrolysis Chlorella residue with polystyrene and waste tires (WTs) results in the production of more stable pyrolysis oil.26 Dan Li et al., on the other hand, chose WTs and three typical waste plastics (PVC, WPp, and PE) as the research objects and examined the properties of the co-pyrolysis process and the product distributions by TG-FTIR/MS technique. The researchers discovered that the DTG curves of the mixtures comprising WTs and PE exhibited multi-stage characteristics. Furthermore, a notable synergistic effect was observed between WTs and PE during the co-pyrolysis process, which is evidenced by the variations in composite pyrolysis indices and activation energies.27 Shukai Shi, Xiaoyan Zhou, and colleagues examined the kinetic parameters and pyrolysis properties of WTs, FLs, and their mixes (1:1 weight ratio). The findings demonstrated that the three samples mostly degraded throughout a wide temperature range of 350 to 450 ℃, and there was a strong correlation between the heating rate and the weight loss rate.28

It has been found that while the academic community has extensively studied the co-pyrolysis of waste tires and other materials, few studies focus on the co-pyrolysis of WTs and WPp, particularly those that thoroughly investigate pyrolysis characterization, kinetic analysis, synergistic effect assessment, and the distribution of pyrolysis products. In order to further supplement and enrich the theoretical basis of co-pyrolysis of WTs and WPp, the individual pyrolysis of WTs and WPp as well as their mixed pyrolysis were selected as the research objects and systematic experimental investigations were conducted in this study. To accurately collect data on the experimental materials' pyrolysis properties, a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) was utilized. Three model-free techniques—the FWO approach, the KAS method, and the Starink method—were then used to predict the kinetic parameters of the pyrolysis process. A comparison between theoretical and real TG-curves was used in order to fully investigate the synergistic impact that exists in the hybrid pyrolysis process of WTs and WPp. As well, the distribution pattern of pyrolysis products, including solid, liquid and gas products, was comprehensively investigated in this study. This thorough research methodology not only aids in uncovering the interaction mechanisms between WPp and WTs during the co-pyrolysis process, but also provides a crucial theoretical foundation and practical guidance for improving the pyrolysis process and elevating the standard of the end product.

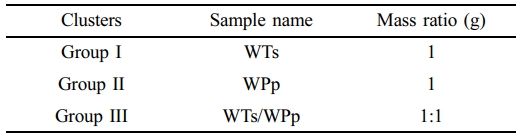

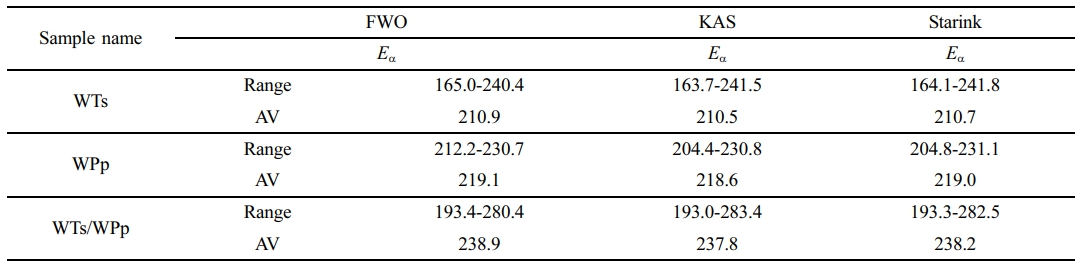

Materials and Methods. Experimental Samples: The used tire samples in this study came from a market for used tires, and the plastic samples were purchased from the second-hand market WPp, using a crusher (DH-PC180, Luoyang Dihai Machinery Co., Ltd.) to crush the WTs and WPp, and filtering out the particles of 0.355 mm of the WPp and WTs by using a standard sieve of 50 mesh, and then grouping the experimental samples, in which the mixing groups were combined in a mass ratio of 1:1.During the mixing process, a Thermo Fisher extruder (Model: Thermo ScientificTM Process 11 Parallel Twin Screw Extruder) was used to mix the pellets several times and repeatedly, while real-time on-line inspection was carried out to ensure homogeneous mixing of the pellets. The grouping outcomes are displayed in Table 1.

Thermogravimetric Analysis: Thermogravimetric analysis is an advanced method employed to investigate the thermal behavior of substances by tracking the sample’s mass in relation to temperature (in ℃) or time (t). The method is usually implemented under preset conditions of constant rate of temperature increase and is one of the key tools for resolving the pyrolysis characteristics of organic solid wastes and their kinetic parameters. In this experiment, three different constant heating rates, i.e., 10 degrees Celsius per minute, 20 degrees Celsius per minute, and 30 degrees Celsius per minute, were used to thermogravimetrically analyze the same batch of samples. During the experiment, the pyrolysis temperature range was precisely set from 40 ℃ to 800 ℃ to ensure that all the critical temperature points where pyrolysis of the samples may occur could be fully covered. High-purity nitrogen was adopted as the purge gas (flow rate 40 mL/min) to maintain the stability and purity of the experimental environment. As well, the crucible used in the experiment is made of high quality alumina, whose excellent thermal stability and chemical inertness can effectively guarantee the precision and consistency of the experimental outcomes.

Kinetic Modeling: During pyrolysis, the test sample undergoes thermal decomposition, resulting in the formation of gaseous, liquid, and solid products. The overall reaction process can be described by the following general expression:

The following symbolic notations were created in formula (1): Initial specimen mass (g) is indicated by W, gaseous phase mass (g) by Wg, liquid fraction (g) by Wo, and solid residual mass (g) by Wr.

The following formula is used to get the conversion rate:

The equation above represents the conversion rate α, where m0 denotes the initial mass of the specimen, measured in milligrams, mₜ refers to the transient mass at the specified thermal condition, and m∞ signifies the asymptotic residual mass upon completion of the process.

The rate of reaction, dα/dt, is governed by the reaction rate constant k(T) and the function f(α), which describes the thermal decomposition mechanism. The correlation between k(T) and the temperature T is given by the Arrhenius equation:

In Equation 3, t denotes time in minutes; f (α) represents the differential form of the pyrolysis mechanism function. The parameter A is identified as the frequency factor, with units of min-1. The variable Eα refers to the activation energy, expressed in kJ/mol. Finally, R stands for the universal gas constant, valued at 8.314 J·mol-1·K-1.

The equation describing the relationship between temperature (T) and time (t) in the non-isothermal context is given by:

β is the heating rate in K/min in formula (4). When formula (4) is substituted into formula (3), the generic formulation for a heterogeneous and non-isothermal reaction is as follows:

In the present research, the activation energy of the kinetics was assessed through the use of a combination of three model-independent approaches: the Flynn-Wall-Ozawa (FWO) method, the Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS) method, and the Starink method. Employing multiple kinetic models for estimating the same sample minimizes relative errors associated with the assessment of a single kinetic model and enhances the reliability of the calculated results.

Model-free Method: The equations of the FWO method are expressed as follows:29

In formula (6), G(α) denotes the integral form of the pyrolysis mechanism function: The KAS method is articulated through the following formulation:30

Starink's equation is expressed as follows:31

Equations (6) to (8) utilize 1/T as the horizontal axis, while ln(β), ln(β/T 2), and ln(β/T1.8) are employed as the vertical axes for the purpose of curve fitting. The slopes of these fitted curves are then analyzed to estimate the activation energy (Eα) at various conversion rates.

Synergistic Effect: In exploring the co-pyrolysis of mixed samples, synergistic effects provide us with an important perspective to reveal the intervals of facilitated or inhibited reactions that may exist.31 By thoroughly analyzing these intervals, we are able to precisely identify which combinations of samples are more effective in reducing energy consumption under co-pyrolysis conditions. In this study, we specifically used the theoretical TG curve method for our analysis. By subtracting the predicted TG curve from the actual TG curve, the synergistic impact during co-pyrolysis was calculated.

Theoretical TG Curve Method: The presence of a synergistic impact during the co-pyrolysis process may be ascertained using the theoretical TG curve approach. The following is the expression for the theoretical TG curve approach:32

In Equation (9), μi denotes the fraction of the total mass corresponding to a single sample, given in weight percent (wt%). Wi denotes the thermal degradation TG of an individual test sample. In this context, TGE refers to the theoretical TG curve, while TGC signifies the actual TG curve. The difference between the theoretical and real TG curves is denoted by the term DWTG.

During the computation described in Equations (9) and (10), When ∆WTG<0, it means that there is a negative synergistic effect occurring during the test samples' co-pyrolysis process. Conversely, if ∆WTG > 0, this implies that a beneficial synergistic impact has occurred.

Pyrolysis Experiment: In order to deeply study the yields of pyrolysis products (including solid, liquid, and gas) of WTs, WPp and WTs/WPp, based on their pyrolysis characteristics, a pyrolysis reactor was employed for the pyrolysis processes of the three samples in the present research. The experimental steps were as follows: first, we accurately weighed the initial mass of the quartz boat, the quartz tube, the oil and gas condensation device, and the liquid oil collection device using high-precision measuring equipment. Then, 10 g of the test sample was placed in the quartz boat, and the sealing devices (including flanges, seals, etc.), the oil and gas condensing device, and the liquid oil collecting mechanism were set up correctly to guarantee the airtightness of the experimental system. Subsequently, we set up a heating program to start from room temperature at a constant rate of 10 ℃/min until the termination pyrolysis temperature was reached and then the experiment was ended. At the conclusion of the experiment, once the equipment had cooled to room temperature, the pyrolysis products were meticulously weighed. This encompassed the accurate measurement of both the pyrolysis oil and the pyrolysis residue. The mass of the pyrolysis gas is obtained by subtracting the sum of these two masses from the total mass.

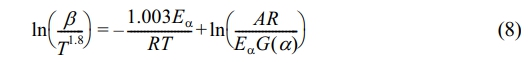

TG-DTG Curve Analysis. The TG-DTG curve, as an effective analytical tool, can comprehensively reflect key information such as the mass loss of the sample, the variation in the pyrolysis rate, the quantity of pyrolysis peaks, and the remaining amount of final residue under varying heating rate conditions (such as 10, 20, and 30 ℃/min) has been observed. Figure 1 illustrates the TG-DTG profiles obtained from the pyrolysis of WTs, WPp alone, and their mixture (WTs/WPp) mixed pyrolysis at these specific heating rates.

A thorough examination of the TG-DTG curves presented in Figure 1 reveals that the overall trends are remarkably similar across the three distinct heating rates of 10, 20, and 30 ℃/min. This observation implies that alterations in the heating rate do not have a considerable impact on the fundamental shape of the TG-DTG curves. However, as the heating rate gradually increases, the TG-DTG curves shift noticeably to higher temperature regions, a phenomenon mainly attributed to the thermal hysteresis revealed in the pyrolysis process.33 Further examination of the DTG curves shows that the peaks at higher heating rates are significantly higher than those at lower heating rates. This phenomenon reveals a positive correlation between the rate of heating and the maximum thermal degradation rate, i.e., the faster the rate of heating, the shorter the exposure time experienced by the experimental samples, which results in a higher maximum thermal degradation rate at increased heating rates.

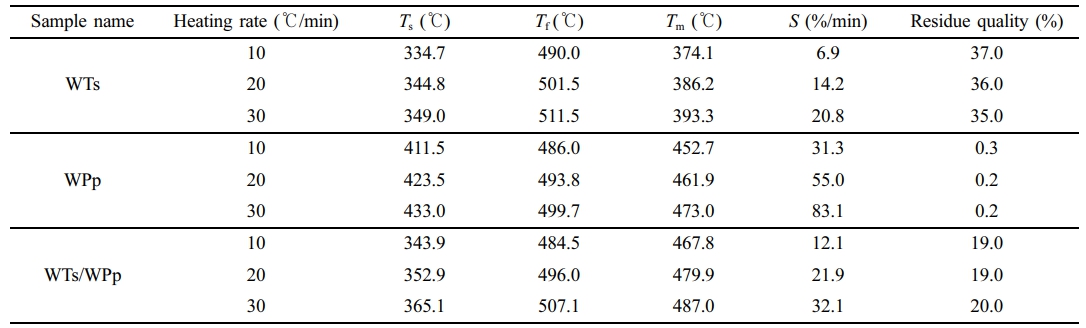

Pyrolysis Characterization. The characterization of pyrolysis encompasses a thorough analysis and interpretation of the thermogravimetric (TG) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves. These curves are instrumental in elucidating the essential pyrolysis parameters of the experimental samples that have been subjected to varying heating rates of 10, 20, and 30 ℃/min. Determining several key parameters, including the maximum weight loss temperature, peak weight loss rate, residual mass, onset and termination pyrolysis temperatures, and others, is part of this characterization. These pyrolysis characteristics enable a deeper understanding of the behavior and pyrolysis process of the experimental materials. Table 2 details the pyrolysis characterization data of WTs, WPp, and WTs/WPp at 10, 20, and 30 ℃/min heating rates.

Combining the information presented in Figure 1 and Table 2, we take the TG-DTG curve at a heating rate of 10 ℃/min as an example for detailed analysis. Figure 1(b) reveals that the pyrolysis of WTs also presented a single weight loss peak, implying that its pyrolysis was also completed in a single stage, with the temperature range of 334.7 ℃ to 490.0 ℃, the maximum weight loss temperature was 374.1 ℃, and the fastest weight loss rate was 6.9%/min. Figure 1(d) clearly shows that the pyrolysis process of WPp presents a significant weight loss peak, indicating that its pyrolysis is completed in a single stage. The temperature range of this stage of pyrolysis was between 411.5 ℃ and 486.0 ℃, and 452.7 ℃ was the temperature at which the greatest weight loss occurred, while the fastest weight loss rate was as high as 31.3%/min. In contrast, Figure 1(f) demonstrates the pyrolysis process of WTs/WPp, with the presence of two distinct weight loss peaks, indicating that its pyrolysis is divided into two stages. The first stage is dominated by the pyrolysis of waste tires, with a temperature interval from 343.9 ℃ to 401.3 ℃, a maximum weight loss temperature of 376.2 ℃, and a fastest weight loss rate of 3.8%/min. The second stage, on the other hand, is mainly induced by the pyrolysis of polypropylene, with a temperature interval extending from 401.3 ℃ to 484.5 ℃, a maximum weight loss temperature of 467.8 ℃, and the quickest rate of weight reduction (12.1%). It is noteworthy that the temperature of mixed pyrolysis appeared delayed phenomenon. The temperature range of the mixed pyrolysis process showed a notable increase, as indicated in Table 2, which is favorable for the effective separation and collection of pyrolysis products because the low rate of temperature increase provides more sufficient time for the reaction to proceed.34

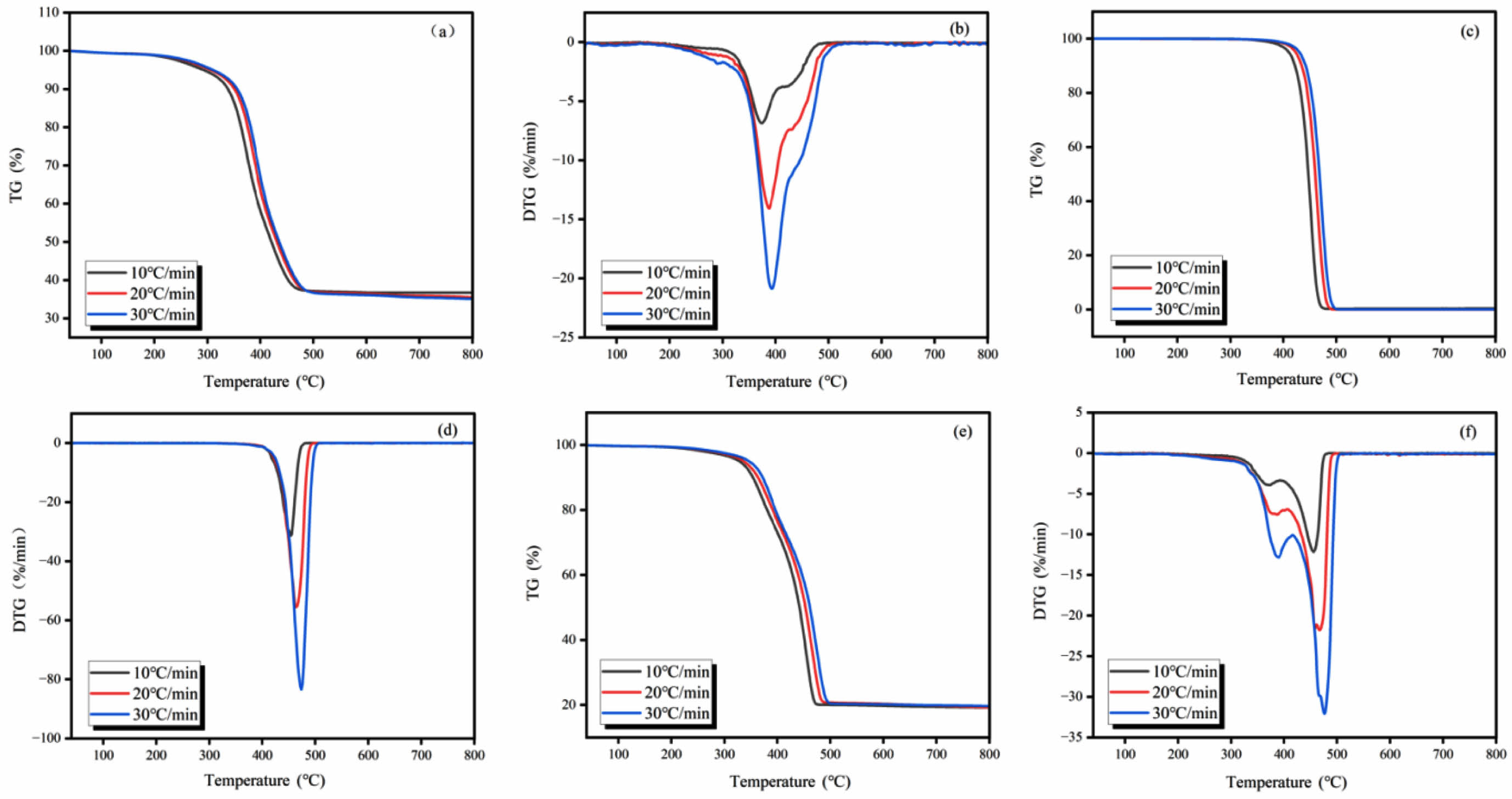

Analysis of Kinetic Parameters. According to Eqs. (6), (7), and (8), the activation energy of WTs, WPp and WTs/WPp model-free methods are derived in a way that the fitted curves of the three model-free methods are shown in Figure 2.

Activation energy is defined as the least amount of energy needed to start a chemical reaction or form an activated complex, often referred to as apparent activation energy. A low activation energy value in a sample indicates that a comparatively small quantity of external energy is needed to propel the pyrolysis reaction at a rapid pace.35 During this experiment, we determined the activation energy of the samples at different conversion rates by fitting the slopes of the resulting curves. Specifically, a range of conversion rates (α) from 0.1 to 0.9 was chosen and measured at 0.1 intervals. Table 3 details the range of kinetic parameters for WTs, WPp and WTs/WPp and their mean values for different kinetic models.

Considering the information shown in Table 3, it is evident that the kinetic parameters (Eα) of the tested samples, which include WTs, WPp, and the combination of WTs/WPp, exhibit variations within a defined range, a phenomenon that reveals the variability of the energy consumption required by the samples at different pyrolysis stages.36 A key observation is that the mean activation energy values calculated through the three kinetic models are strikingly similar, a phenomenon that verifies the reliability of the three model-free calculations for the activation energy. Further analysis reveals that WTs/WPp> WPp>WTs, which is attributed to the higher pyrolysis temperature required in the mixed pyrolysis of WPp and WTs, resulting in the maximum activation energy of WTs/WPp.

Waste tires have a pyrolysis activation energy between 149 and 244 kJ/mol.37 The range of its pyrolysis activation energy is relatively large. This is because the composition of tires is complex and the composition of different brands varies greatly. The activation energy value of this experiment is 210.5-210.9 kJ/mol, which is in a relatively high range. The pyrolysis activation energy of WPp is in the range of 226.92-227.37 kJ/mol.38 The activation energy value of this experiment is 218.6-219.1 kJ/mol, which is smaller than the range in the literature. The main reasons for the difference are, firstly, related to the particle diameter of the material. The particles (0.355 mm) used in this experiment have a small diameter, resulting in a uniform temperature distribution across the experimental material, which contributes to the low activation energy.39 On the other hand, since this experiment uses waste polypropylene, which comes from the second-hand market, it may be different in composition from that used in the literature research, and there are errors in the calculation process, which all cause the difference in the calculated activation energy.

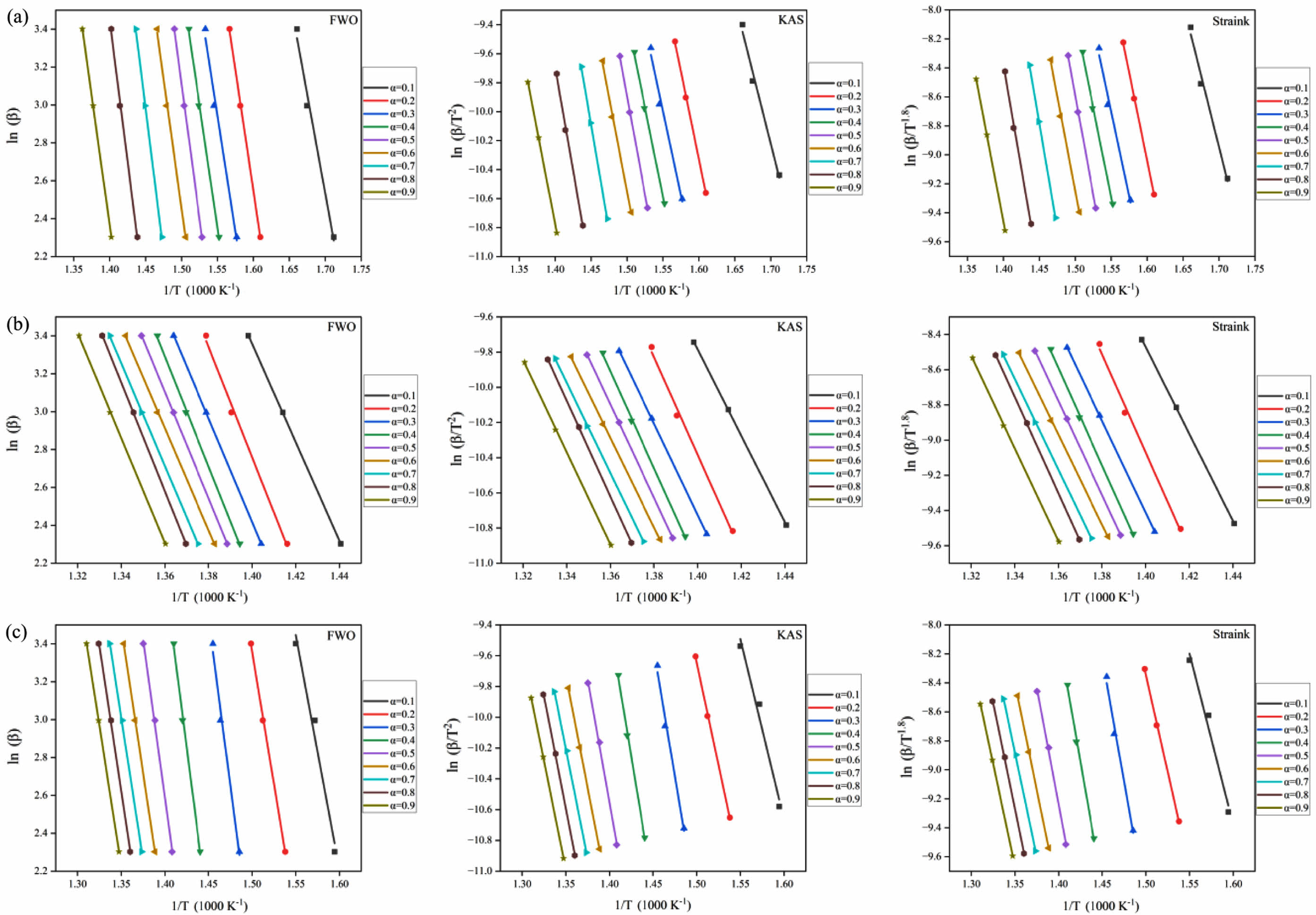

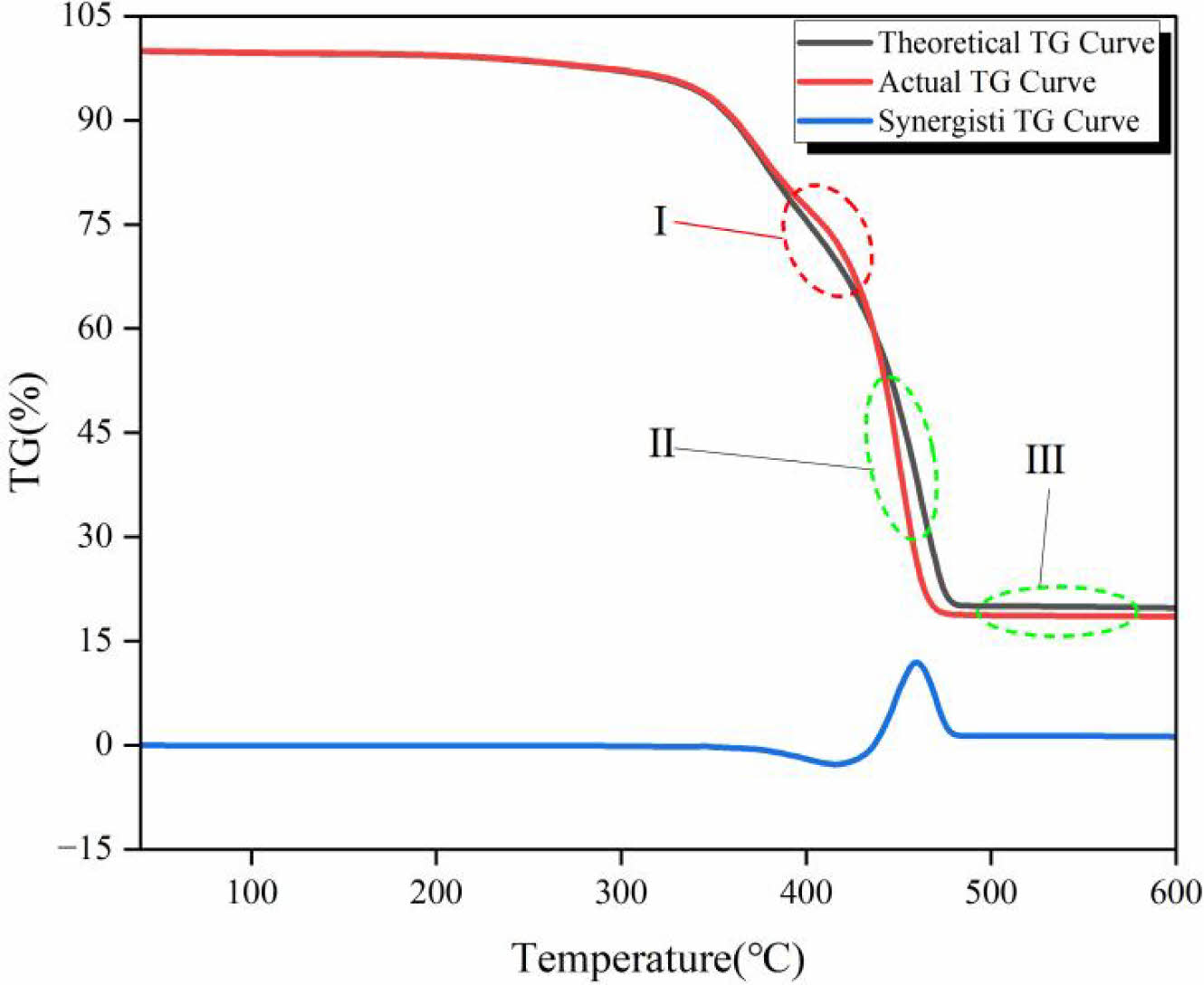

Synergy Analysis. Synergism is regarded as an important indicator for assessing the level of energy consumption of multiple samples during the co-pyrolysis process. By analyzing the theoretical TG-DTG curves, we can visualize the intensity of synergism and its action interval during the co-pyrolysis of WTs and WPp. Figure 3 displays the predicted TG-DTG curves for WTs/WPp co-pyrolysis at a heating rate of 10 degrees Celsius per minute.

Figure 3 reveals the characterization of the synergistic interaction of WTs/WPp during pyrolysis. It can be observed that the pyrolysis of WTs/WPp is mainly affected by positive synergism. Specifically, the actual TG curve was higher than the theoretical TG curve overall when the experimental samples' pyrolysis temperature was between 352 and 436 ℃, as indicated by ΔWTG<0, and a negative synergistic interval appeared as stage Ⅰ, which indicated that this stage had an unfavorable effect on the co-pyrolysis of the mixed samples, and the pyrolysis process was mainly suppressed. The synergistic inhibition at the very beginning of stage Ⅰ is because the plastic is co-mingled with tires, which is accompanied by the process of heat transfer when heating, and the WPp itself has poor thermal conductivity, which hinders the cracking of waste tires, and it will cause a part of the temperature to be delayed backward. At temperatures ranging from 436 ℃ to 600 ℃, the actual TG curve lies beneath the theoretical TG curve, and DWTG>0, indicating that it enters a positive synergistic interval for the Ⅱ and Ⅲ stages, and the pyrolysis process is mainly promoted. The positive synergistic effect in stages II and III may be due to the fact that some product produced by the tire promotes the pyrolysis of WPp.40 Although the theoretical TG curves also exhibited a negative synergistic interval in the temperature interval from 352 ℃ to 436 ℃, the temperature interval of positive synergistic effect continued from 436 ℃ to the end of pyrolysis as the temperature continued to increase and its range far exceeded the negative synergistic interval, which indicated that positive synergistic effect was dominant in the whole pyrolysis process. From stage III, it can be seen that the actual residue is less than the theoretical residue, and the residue is more converted to cracking oil or pyrolysis gas after the actual mixed cracking of WTs/WPp, this demonstrates that the positive synergism governs the entire cracking process.

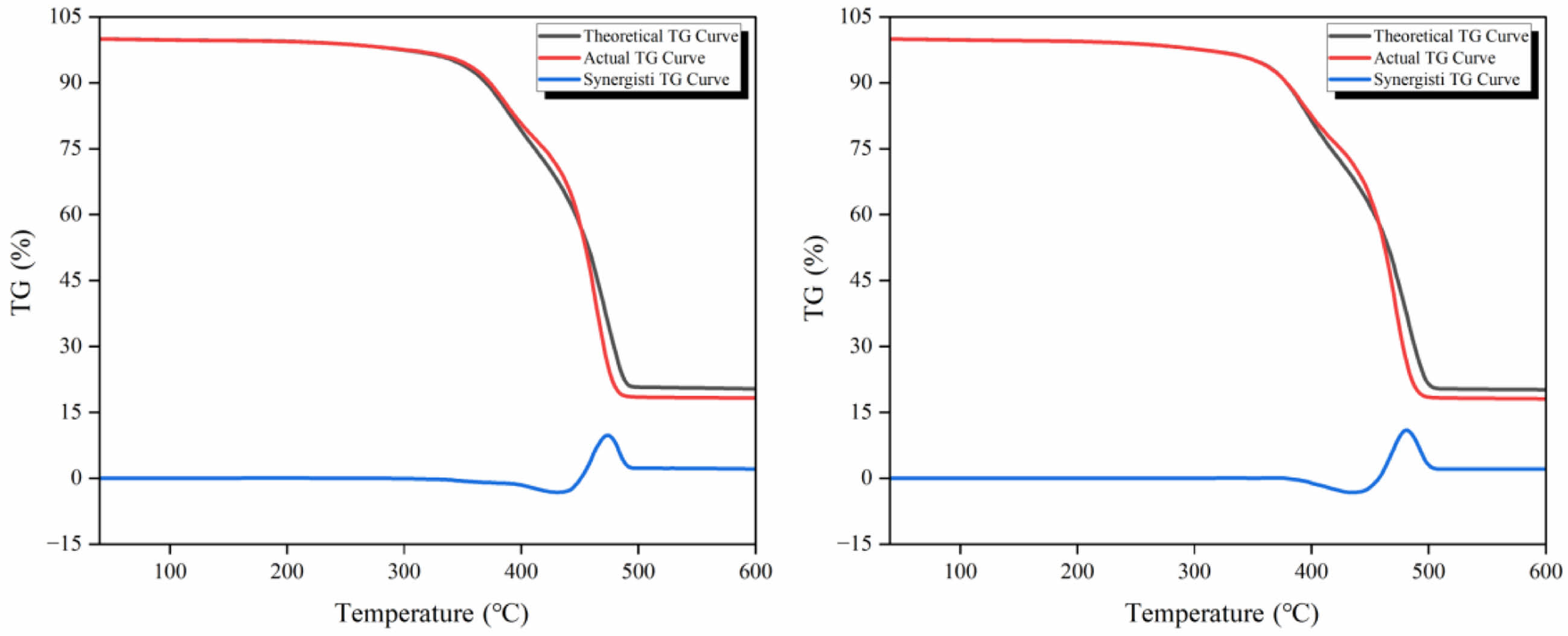

By comparing the curves in Figures 3 and 4 at the three rates of warming, two things were discovered. First, a change in the rate of warming does not change the trend of pyrolysis and does not change the category of synergistic effect. Second, the greater the rate of warming, the more pronounced the synergistic effect. Although the synergistic synergy is more obvious with an increase in the rate of warming, more pyrolysis gas is produced with an increase in the rate of warming, and the purpose of this study is to produce more pyrolysis oil, while too fast a rate of temperature rise is not favorable to the production of oil,41 The pyrolysis reaction studies were conducted at a rate of warming of 10 ℃/min.

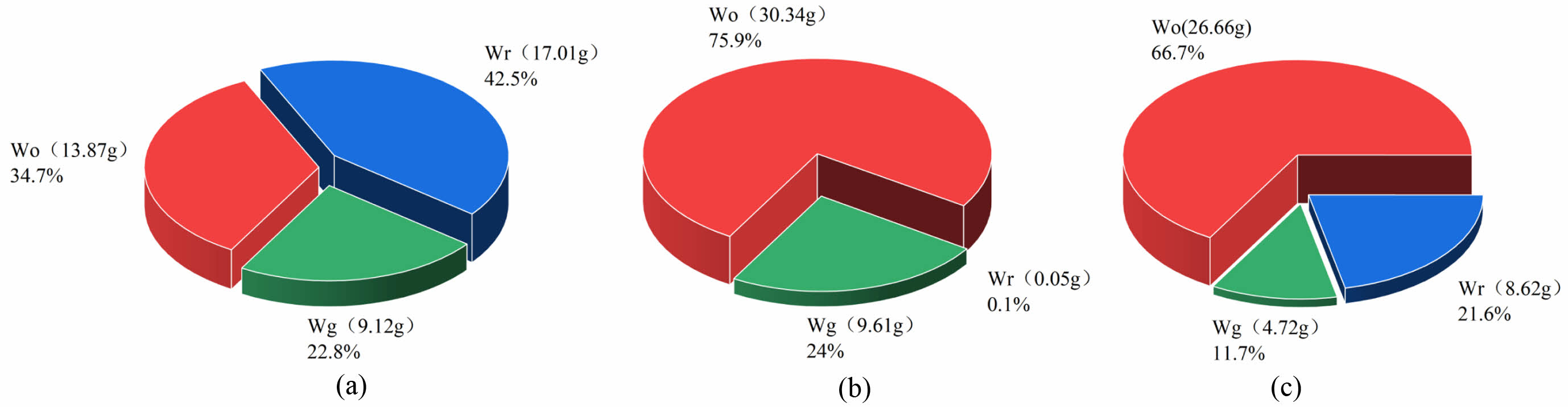

Analysis of Pyrolysis Products. The solid-liquid-gas ratio formed after pyrolysis of WTs is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 clearly demonstrates the distribution of pyrolysis products of WTs, WPp and WTs/WPp in the temperature interval from warming up to 600 ℃. In the same temperature interval, the percentages of pyrolysis oil, residue and pyrolysis gas in the pyrolysis products of WTs, on the other hand, were 34.7%, 42.5%, and 22.8%(the error is within ±2%). Specifically, the percentages of pyrolysis oil, residue and pyrolysis gas in the pyrolysis products of WPp were 75.9%, 0.1%, and 24% (the error is within ±2%), respectively, while for the co-pyrolysis products of WTs/WPp, the percentages of pyrolysis oil, residue and pyrolysis gas were 66.7%, 21.6%, and 11.7% (the error is within ±2%), respectively. Based on the actual conversion of WTs and WPp, we can deduce the theoretical product distribution of WTs/WPp co-pyrolysis: pyrolysis oil, residue and pyrolysis gas should account for 55.3%, 21.28%, and 23.4%, respectively. By comparing the actual co-pyrolysis product distribution of WTs/WPp with the theoretical values, we found that the actual oil production rate (66.7%) was 11.4% higher than the theoretical rate (55.3%), demonstrating that the co-pyrolysis process's pyrolysis oil output rate was noticeably greater than the anticipated value, and this result revealed the advantage of the co-pyrolysis of WTs/WPp in improving the pyrolysis oil production rate.In the process of mixed pyrolysis of WTs and WPp, tires were cracked first, then residue and pyrolysis gas. In the mixed pyrolysis process involving WTs and WPp, the process of turning cracking gas into useful cracking oil is greatly aided by the carbon black residue left behind following the tires' first cracking.40

Discussion. This research is done in the laboratory, due to the sample size is relatively small, its heat and mass transfer is uniform and easy to control. When expanding to the industrialized production scale or pilot process, due to the material mass increases a lot, its heat transfer, mass transfer process, etc. are changed, and the requirements for the equipment are more stringent, we need to conduct a large number of experiments in order to carry out the investigation, which is the direction of the follow-up we continue to improve. The key research directions in the future will focus on: (1) quantitative characterization of heat/mass transfer kinetics in the reactor through experimental measurements and CFD simulations; (2) systematic optimization of key process parameters in order to guarantee the homogeneity and efficiency under a larger operating volume; (3) rigorous evaluation of equipment performance indexes and design requirements in order to guarantee the equipment requirements from laboratory research to industrial applications. All these studies will facilitate the better translation of research results into industrial applications.

|

Figure 1 TG-DTG curves of WTs, WPp, and WTs/WPp. |

|

Figure 2 Model-free fitting method for WTs, WPp and WTs/WPp. |

|

Figure 3 Theoretical TG curves of WTs/WPp under the warming rate of 10 ℃/min. |

|

Figure 4 Theoretical TG curves of WTs/WPp under the heating rate of 20 ℃/min and 30 ℃/min. |

|

Figure 5 The composition ratio of pyrolysis products: WPp (a); WTs (b) and WTs/WPp. Note: Wz represents total mass, Wo represents quality of pyrolysis oil, Wr represents quality of pyrolysi residue, Wg represents quality of pyrolysis gas. |

|

Table 2 Pyrolytic Properties of WPp, WTs, and WTs/WPp |

Note: Ts, Tf, Tm and S are the onset pyrolysis temperature, termination pyrolysis temperature, maximum weight loss temperature, and fastest weight loss rate, respectively |

In this thesis, with the aid of a thermogravimetric analyzer, the individual pyrolysis of WTs and WPp as well as the co-pyrolysis of WTs/WPp were comprehensively and thoroughly analyzed, focusing on the pyrolysis characteristics, kinetic parameters, synergistic effects, and the distribution patterns of the pyrolysis products (solid, liquid, and gaseous) of these processes, and based on which, the following deductions were made:

(1) Thermogravimetric analysis results showed that, in contrast to the independent pyrolysis of WTs and WPp, the mixed pyrolysis of WTs/WPp delayed the overall pyrolysis temperature, expanded the temperature distribution range of the mixed pyrolysis, and facilitated the separation and recovery of pyrolysis products.

(2) Three model-free techniques were used for the calculations, and the outcomes consistently demonstrated that the real average activation energy in WTs/WPp co-pyrolysis was larger than that in WPp and WTs pyrolysis.

(3) The WTs/WPp co-pyrolysis process primarily showed positive synergistic effects, according to an analysis of the synergistic effects. This finding implies that the co-pyrolysis of WTs/WPp helps to lower the energy consumption in the pyrolysis process.

(4) Pyrolysis tests were conducted on three samples of WTs, WPp, and WTs/WPp using the pyrolysis reactor apparatus. The experimental findings indicated that the WTs/WPp co-pyrolysis method was advantageous for oil production and disadvantageous for gas production.

- 1. Kazemi, M.; Parikhah Zarmehr, S.; Yazdani, H.; Fini, E. Review and Perspectives of End-of-life Tires Applications for Fuel and Products. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 10758-10774.

-

- 2. Goevert, D. The Value of Different Recycling Technologies for Waste Rubber Tires in the Circular Economy—a Review. Frontiers Sustainab. 2024, 4, 1282805.

-

- 3. Yaghi, A.; Ali, L.; Altarawneh, M. Recent Advances on Thermochemical Recycling of End-of-Life Tires and Their Coblending with Waste Plastic Fractions. ACS omega 2025, 10, 26233-26249.

-

- 4. Zhao, Q.; Wu, Y.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Zhu, H.; He, W.; Li, G. Pathways to Carbon Neutrality: A Review of Life Cycle Assessment-Based Waste Tire Recycling Technologies and Future Trends. Processes 2025, 13, 741.

-

- 5. Han, W.; Han, D.; Chen, H. Pyrolysis of Waste Tires: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 1604.

-

- 6. Xu, J.; Yu, J.; Xu, J.; Sun, C.; He, W., Huang, J.; Li, G. High-value Utilization of Waste Tires: A Review with Focus on Modified Carbon Black from Pyrolysis. Sci. Total Environm. 2020, 742, 140235.

-

- 7. Czarna-Juszkiewicz, D.; Kunecki, P.; Cader, J.; Wdowin, M. Review in Waste Tire Management—potential Applications in Mitigating Environmental Pollution. Materials 2023, 16, 5771.

-

- 8. Dwivedi, C.; Manjare, S.; Rajan, S. K. Recycling of Waste Tire by Pyrolysis to Recover Carbon Black: Alternative & Environment-friendly Reinforcing Filler for Natural Rubber Compounds. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2020, 200, 108346.

-

- 9. Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, A.; Ivanovich Vatin, N.; Mohamed, A. M.; Deifalla, A. F.; Mehmood, I. Plastic Waste Management Strategies and Their Environmental Aspects: A Scientometric Analysis and Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Environm. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4556.

-

- 10. Armenise, S.; SyieLuing, W.; Ramírez-Velásquez; J. M., Launay, F.; Wuebben, D.; Ngadi, N.; Rams, J.; Munoz, M. Plastic Waste Recycling via Pyrolysis: A Bibliometric Survey and Literature Review. J. Analytical Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 158, 105265.

-

- 11. MacLeod, M.; Arp, H. P. H.; Tekman, M. B.; Jahnke, A. The Global Threat From Plastic Pollution. Science 2021, 373, 61-65.

- 12. Williams, A. T.; Rangel-Buitrago, N. The Past, Present, and Future of Plastic Pollution. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 176, 113429.

-

- 13. Kang, H. K.; Yu, M. J.; Park, S. H.; Jeon, J. K.; Kim, S. C.; Park, Y. K. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Miscanthus and Random Polypropylene over SAPO-11. Polym. Korea 2013, 37, 379-386.

-

- 14. Sri Sasi Jyothsna, T.; Chakradhar, B. Current Scenario of Plastic Waste Management in India: Way Forward in Turning Vision to Reality. In Urban Mining and Sustainable Waste Management. Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp 203-218.

-

- 15. Lee, D. H.; Choi, H. J.; Kim, D. S.; Lee, B. H. Distribution Characteristics of Pyrolysis Products of Polyethylene. Polym. Korea 2008, 32, 157-162.

- 16. Kumar, S; Panda, A. K.; Singh, R. K. A Review on Tertiary Recycling of High-density Polyethylene to Fuel. Resources Conserv. Recyc. 2011, 55, 893-910.

-

- 17. Sharuddin, S. D. A.; Abnisa, F.; Daud, W. M. A. W.; Aroua, M. K. A Review on Pyrolysis of Plastic Wastes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 115, 308-326.

-

- 18. Al-Salem, S. M.; Antelava, A.; Constantinou, A.; Manos, G.; Dutta, A. A Review on Thermal and Catalytic Pyrolysis of Plastic Solid Waste (PSW). J. Environm. Manag. 2017, 197, 177-198.

-

- 19. Chen, W. H.; Naveen, C.; Ghodke, P. K.; Sharma, A. K.; Bobde, P. Co-pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass with Other Carbonaceous Materials: A Review on Advance Technologies, Synergistic Effect, and Future Prospectus. Fuel 2023, 345, 128177.

-

- 20. Chang, S. H. Plastic Waste as Pyrolysis Feedstock for Plastic Oil Production: A Review. Sci. Total Environm. 2023, 877, 162719.

-

- 21. Zerin, N. H.; Rasul, M. G.; Jahirul, M. I.; Sayem, A. S. M. End-of-life Tyre Conversion to Energy: A Review on Pyrolysis and Activated Carbon Production Processes and Their Challenges. Sci. Total Environm. 2023, 905, 166981.

-

- 22. Maqsood, T.; Dai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Guang, M.; Li, B. Pyrolysis of Plastic Species: A Review of Resources and Products. J. Analytical Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 159, 105295.

-

- 23. Grioui, N.; Halouani, K.; Agblevor, F. A. Assessment of Upgrading Ability and Limitations of Slow Co-pyrolysis: Case of Olive Mill Wastewater Sludge/waste Tires Slow Co-pyrolysis. Waste Manag.2019, 92, 75-88.

-

- 24. Sanahuja-Parejo, O.; Veses, A.; López, J. M.; Murillo, R.; Callén, M. S.; García, T. Ca-based Catalysts for the Production of High-quality Bio-oils From the Catalytic Co-pyrolysis of Grape Seeds and Waste Tyres. Catalysts 2019, 9, 992.

-

- 25. Campuzano, F.; Ortíz, C. F.; Betancur, M.; Martínez, J. D. Characterization of Three Different Solid Wastes as Energy Resources for Pyrolysis. 2018 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. U.K., 2018, 437, 012002.

-

- 26. Kumar, A.; Yan, B.; Cheng, Z.; Tao, J.; Hassan, M.; Li, J.; Kumari, L.; Tafa, O.B.; Akintayo, A.M.; Ali, J.I.; Chen, G. Co-pyrolysis of Hydrothermally Pre-treated Microalgae Residue and Polymeric Waste (plastic/tires): Comparative and Dynamic Analyses of Pyrolytic Behaviors, Kinetics, Chars, Oils, and In Situ Gas Emissions. Fuel. 2023, 331, 125814.

-

- 27. Li, D.; Lei, S.; Rajput, G.; Zhong, L.; Ma, W.; Chen, G. Study on the Co-pyrolysis of Waste Tires and Plastics. Energy 2021, 226, 120381.

-

- 28. Shi, S.; Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Nguyen, T.; Chen, M. Thermal and Kinetic Behaviors of Fallen Leaves and Waste Tires Using Thermogravimetric Analysis. BioResources 2017, 12, 4707-4721.

-

- 29. Yao, Z.; Yu, S.; Su, W.; Wu, W.; Tang, J.; Qi, W. Kinetic Studies on the Pyrolysis of Plastic Waste Using a Combination of Model-fitting and Model-free Methods. Waste Manag. Res. 2020, 38, 77-85.

-

- 30. Nisar, J.; Ali, G.; Shah, A.; Farooqi, Z. H.; Khan, R. A.; Iqbal, M.; Gul, M. Pyrolysis of Waste Tire Rubber: A Comparative Kinetic Study Using Different Models. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utili. Environ. Effects 2024, 46, 12710-12720.

-

- 31. Shan, T.; Bian, H.; Wang, K.; Li, Z.; Qiu, J.; Zhu, D.; Wang, C.; Tian, X. Study on Pyrolysis Characteristics and Kinetics of Mixed Waste Plastics Under Different Atmospheres. Thermochimica Acta 2023, 722, 179467.

-

- 32. Kai, X.; Yang, T.; Shen, S.; Li, R. TG-FTIR-MS Study of Synergistic Effects During Co-pyrolysis of Corn Stalk and High-density Polyethylene (HDPE). Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 181, 202-213.

-

- 33. Xu, F.; Wang, B.; Yang, D.; Hao, J.; Qiao, Y.; Tian, Y. Thermal Degradation of Typical Plastics Under High Heating Rate Conditions by TG-FTIR: Pyrolysis Behaviors and Kinetic Analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 171, 1106-1115.

-

- 34. Ylitervo, P.; Richards, T. Gaseous Products From Primary Reactions of Fast Plastic Pyrolysis. J. Analytical Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 158, 105248.

-

- 35. Shahid, A.; Ishfaq, M.; Ahmad, M. S.; Malik, S.; Farooq, M.; Hui, Z.; Batawi, A. H.; Shafi, M. E.; Aloqbi, A. A.; Gull, M.; Mehmood, M. A. Bioenergy Potential of the Residual Microalgal Biomass Produced in City Wastewater Assessed Through Pyrolysis, Kinetics and Thermodynamics Study to Design Algal Biorefinery. Bioresource Technol. 2019, 289, 121701.

-

- 36. Hadigheh, S. A.; Wei, Y.; Kashi, S. Optimisation of CFRP Composite Recycling Process Based on Energy Consumption, Kinetic Behaviour and Thermal Degradation Mechanism of Recycled Carbon Fibre. J. Cleaner Production 2021, 292, 125994.

-

- 37. Jiang, L.; Yang, X. R.; Gao, X.; Xu, Q.; Das, O.; Sun, J. H.; Kuzman, M. K. Pyrolytic Kinetics of Polystyrene Particle in Nitrogen Atmosphere: Particle Size Effects and Application of Distributed Activation Energy Method. Polymers 2020, 12, 421.

-

- 38. Chen, J.; Ma, X.; Yu, Z.; Deng, T.; Chen, X.; Chen, L.; Dai, M. A Study on Catalytic Co-pyrolysis of Kitchen Waste with Tire Waste over ZSM-5 Using TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS. Bioresource Technol. 2019, 289, 121585.

-

- 39. Hu, Q.; Tang, Z.; Yao, D.; Yang, H.; Shao, J.; Chen, H. Thermal Behavior, Kinetics and Gas Evolution Characteristics for the Co-pyrolysis of Real-world Plastic and Tyre Wastes. J. Cleaner Production 2020, 260, 121102.

-

- 40. Alzahrani, N.; Nahil, M. A.; Williams, P. T. Co-pyrolysis of Waste Plastics and Tires: Influence of Interaction on Product Oil and Gas Composition. J. Energy Institute 2025, 118, 101908.

-

- 41. Singh, R. K.; Ruj, B.; Sadhukhan, A. K.; Gupta, P. Impact of Fast and Slow Pyrolysis on the Degradation of Mixed Plastic Waste: Product Yield Analysis and Their Characterization. J. Energy Institute 2019, 92, 1647-1657.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 49(6): 738-748

Published online Nov 25, 2025

- 10.7317/pk.2025.49.6.738

- Received on Apr 1, 2025

- Revised on Aug 9, 2025

- Accepted on Aug 12, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Weiquan Chen

-

Dongying Vocational College of Science and Technology, No. 361, Yingbin Road, Guangrao County, Dongying City, Shandong Province, China, 257300, China

- E-mail: chenweiquan@dykj.edu.cn

- ORCID:

0009-0008-4142-8288

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.