- Multifunctional Performance of PET Bottles Reinforced with Silica-Polystyrene Nanocomposites: Enhanced Mechanical, Thermal, Rheological, and Barrier Properties

Department of Mechanical and Systems Engineering, Hansung University, 116 Samseongyo-ro 16gil, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02876, Korea

- 실리카 나노 복합체 적용으로 보강된 다기능성 PET병의 기계적, 열적, 유변학적 및 배리어 기능

한성대학교 기계전자공학부

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

Core-shell SiOx (silicate core)/PS (shell) nanoparticles were blended with polyethylene terephthalate (PET) resin and fabricated into nanocomposites via melt compounding, followed by bottle manufacturing for cosmetic packaging applications. The effects of nanoparticle loading on mechanical and thermal properties were investigated. A loading of 0.5-4.0 wt% resulted in the highest tensile strength (69.72 ± 4.93 MPa), Young’s modulus (887.58 ± 19.50 MPa), Izod impact strength (34.7 J/m) and a 13.9% increase in crystallinity. Frequency sweep tests revealed an increase in complex viscosity and slower stress relaxation due to restricted chain mobility. The storage modulus (G') slope decreased from G' ~ω0.79 (pristine PET) to G'~ω0.67 (0.5-4.0 wt%), indicating a transition of the polymer matrix toward more elastic, solid-like behavior. At 0.5-4.0 wt%, a 98.1% reduction in O2 transmission rate (OTR) and a 97.7% decrease in permeability were observed, confirming the enhanced multifunctional performance of PET bottles.

실리케이트(SiOx) 코어와 폴리스티렌(PS) 쉘로 구성된 코어쉘 구조의 SiOx/PS 나노 입자를 페트(PET)수지와 혼합하고 용융 혼련 공정을 통해 기능성 마스터배치 형태의 나노 복합체로 제조한 후 이를 각기 다른 비율별로 혼합하여 화장품 포장용기로 적용하기위한 투명한 페트병을 제작하였다. 나노 입자의 첨가가 페트병의 기계적, 열적 특성에 미치는 영향을 측정한 결과, 0.5-4.0 wt%의 비율에서 인장강도(69.72 ± 4.93 MPa), 영률(887.58 ± 19.50 MPa), 아이조드 충격강도(34.7 J/m)가 최대로 증가하였고 결정화도는 13.9% 증가하였다. 점탄성 특성 테스트 결과 고분자 사슬의 운동성의 제한효과에 기인한 복합 점도의 증가와 응력이완 속도의 감소가 확인되었다. 저장 탄성율(G')의 기울기는 G'~ω0.79(pristine PET)에서 G'~ω0.67(0.5-4.0 wt%)로 감소되었으며 이는 고분자의 특성이 탄성적 특성이 강한 고체적 성질로 전이한 것을 의미한다. 0.5-4.0 wt%의 비율로 제작된 페트병에서 산소 투과도가 98.1% 감소하였으며 산소 투과율은 97.7% 감소함을 확인하였고 이는 페트병의 기계적, 열적, 유변학적 기능의 향상을 의미한다.

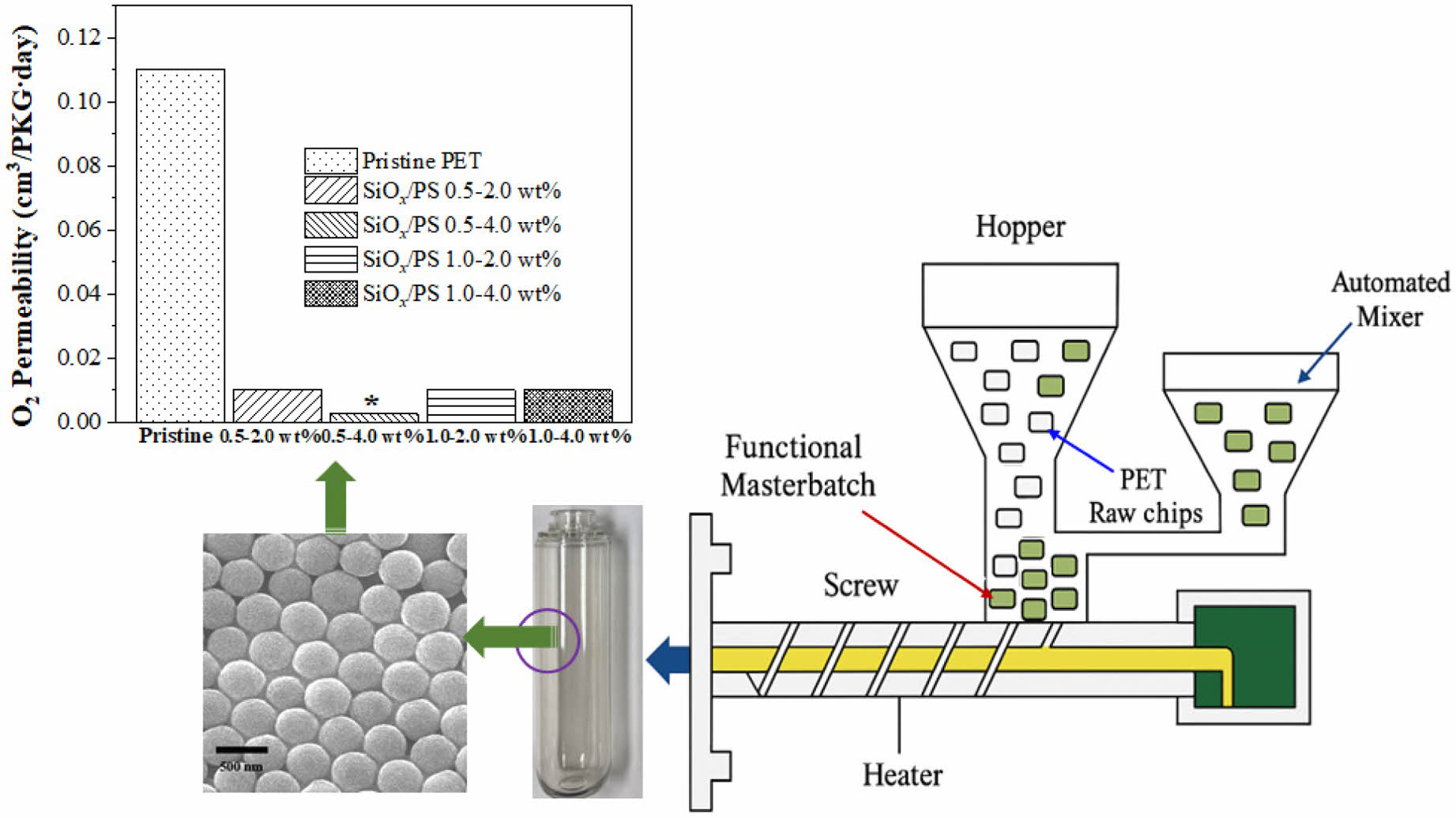

Core-shell SiOx/polystyrene (PS) nanoparticles were blended with polyethylene terephthalate (PET) base resin and fabricated nanocomposites as functional masterbatch via melt compounding. The resulting masterbatch was then mixed with PET base resin and processed by blow molding to manufacture transparent PET bottles with significantly enhanced oxygen barrier properties.

Keywords: silicate-polystyrene nanocomposites, poly(ethylene terephthalate) bottles, rheology, oxygen transmission, mechanical properties.

The author is thankful to Dr. Lord and Mr. Mario for their assistance in preparing the experimental setup and manuscript. This work was financially supported by Hansung University.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a semicrystalline thermoplastic polymer, has been extensively used in packaging applications, such as bottles, laminates, and fibers due to its satisfactory mechanical strength, transparency, and processability.1,2 However, the relatively high gas permeability of PET has limited its suitability for products that are sensitive to oxidation, given the fact that no polymers are entirely crystalline and all exhibit a certain degree of gas diffusion. Semicrystalline PET is particularly susceptible to oxygen permeation in applications such as liquid-type cosmetics, in which the degradation of active ingredients may occur due to exposure to oxygen.3 To address this limitation, many studies have attempted to improve the oxygen barrier properties of PET by modifying its material characteristics through blending with organic or inorganic fillers, which are known to induce structural reorganization that hinders the diffusion of gas molecules. A variety of nanofillers, including nanoclays, metal oxides, and carbon nanotubes (CNTs), have been used for this purpose. Of these, nanoclays have attracted significant attention due to their high dispersion capability within the PET matrix. Their incorporation has been reported to improve the thermal, mechanical, and barrier properties of pristine PET.4,5

Enhancement of barrier performance in PET has been found to be closely related to changes in thermal, mechanical, and rheological behavior, which are influenced by the dispersion state of nanoparticles, interfacial interactions, and filler loading. Improvements in tensile strength and Young’s modulus have been observed following nanoparticle incorporation, contributing to increased stiffness and effective load transfer across the polymer-nanoparticle interface. Such structural reinforcement restricts polymer chain mobility, which not only enhances mechanical properties but also reduces free volume and available diffusion pathways. Furthermore, improved interfacial adhesion between the polymer matrix and nanoparticles has been shown to facilitate energy dissipation under mechanical loading, thereby enhancing impact resistance (e.g., Izod strength).

In addition to mechanical properties, rheological measurements have provided valuable insights into the structural reorganization of PET nanocomposites under shear deformation.4,6 The incorporation of nanofillers such as clay, CNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles has been shown to increase the storage modulus (G'), indicating a transition toward more solid-like behavior.7-10 This response has been attributed to physical network formation and strong interfacial interactions, both of which restrict polymer chain mobility. A reduction in the power law slope of G' versus angular frequency (ω) in the terminal zone is associated with filler networking, aggregation, and percolation phenomena in PET-based nanocomposites.11-13 Complex viscosity (η) indicates the ability of polymer chains to rearrange under applied shear, which is governed by interfacial friction between the polymer chains and nanofiller surfaces. The incorporation of nanoparticles typically leads to higher viscosity compared to neat PET, resulting in increased resistance to flow. Most polymer melts exhibit non-Newtonian, shear thinning behavior, in which viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate due to the disruption or rearrangement of particle aggregates.14

Crystallinity, as determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), is another important structural factor that influences the barrier behavior of PET. Improved barrier performance following the incorporation of nanofillers has been associated with an increase in crystallinity, which is induced by interactions between the nanofillers and PET chains, particularly within the semicrystalline regions. These interactions promote the formation of denser and more ordered crystalline structures, and effectively limit the diffusion of gas molecules compared to the unmodified matrix. Therefore, filler-induced crystallization and the development of more tightly packed crystalline domains can contribute significantly to the reduction of oxygen transmission.

The barrier performance of PET is directly linked to the presence of free volume, a diffusion pathway for gas molecules that originates from random thermal motion or insufficient packing of polymer segments.15,16 A well-dispersed and aligned nanofiller phase within the polymer matrix can create tortuous diffusion paths or induce partial immobilization of polymer chains in the vicinity of filler surfaces, which suppresses gas transport through interfacial regions. Additionally, the incorporation of nanoparticles can physically occupy and block free volume regions (i.e., pores or voids), thereby inhibiting diffusion of gas molecules.17 The oxygen barrier performance of PET has therefore been recognized as a function of matrix composition, filler content, crystallinity, and microstructural arrangement. However, most studies have focused on PET-nanoclay nanocomposites prepared in the form of films, sheets, or pellets, rather than fully shaped PET bottles.7,18,19

In this study, transparent PET bottles were fabricated for cosmetic packaging applications using SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites, with the aim of reducing oxygen transmission. The functional master batch (SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposite) was prepared by melt compounding core-shell type SiOx/PS nanoparticles with thermoplastic PET base resin using a twin screw extruder. The effects of SiOx/PS nanoparticle loading on the thermal behavior, mechanical performance, and rheological response of PET bottles were systematically investigated, along with the evaluation of oxygen transmission rate (OTR). A filler loading range of 0.5-4.0 wt% was identified as effective in enhancing the oxygen barrier performance relative to pristine PET.

Materials. To form the silicate core of the SiOx/PS nanoparticle, natural Hwangtoh clay - a Korean yellow loess - was purchased from Gochang, Jeollabukdo, Korea. To synthesize the polystyrene shell, styrene monomer (³ 99%), divinylbenzene (³ 55%, crosslinker), and potassium persulfate (³ 99%, initiator) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) resin (pristine PET) with an intrinsic viscosity (IV) of 0.76 dL/g and a density of 1.40 ± 0.01 g/cm3 was purchased from Lotte Chemical (Ulsan, Korea). For the preparation of SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposite, the following additives were used during the melt extrusion process: a lubricant (LicoWax E, Clariant, Basel, Switzerland), a hydrolytically stable processing agent (Irgafos 168, Ciba Inc., Basel, Switzerland), a thermal stabilizer antioxidant (Irganox 1010, Ciba Inc., Basel, Switzerland), and an anti-hydrolysis agent (ZIKA-AH 362, Ziko, Korea).

Nanoparticle Preparation and Characterization. The SiOx/PS nanoparticles were synthesized following a previously published method.20 The nanoparticles are a core-shell heterostructure, consisting of a SiOx(silicate) core surrounded by a thin polystyrene (PS) shell. Hwangtoh clay with a median size of 2.5 μm was mechanically ground using an Auto Mortar AMM-140D (AS ONE, Osaka, Japan) at 120 rpm (pestle) and 7 rpm (mortar) for 30 min. The ground powder was dispersed in distilled water and stirred for 24 h to obtain a 1.0% (w/v) aqueous suspension. After 24 h, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter (HVLP04700, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), and the collected Hwangtoh particles were harvested as the source of SiOx. To form the PS shell around the SiOx core, emulsion polymerization was conducted by mixing styrene monomer, divinylbenzene (crosslinker), and potassium persulfate (initiator) in a 1.0:0.1:0.01 ratio with the filtered SiOx particles. The reaction was carried out at 74 ℃ for 7 h in an aqueous phase. The particles were collected as a powder and dried at 80 ℃ for 12 h to remove any residual moisture and stored for subsequent melt compounding with the PET base resin.

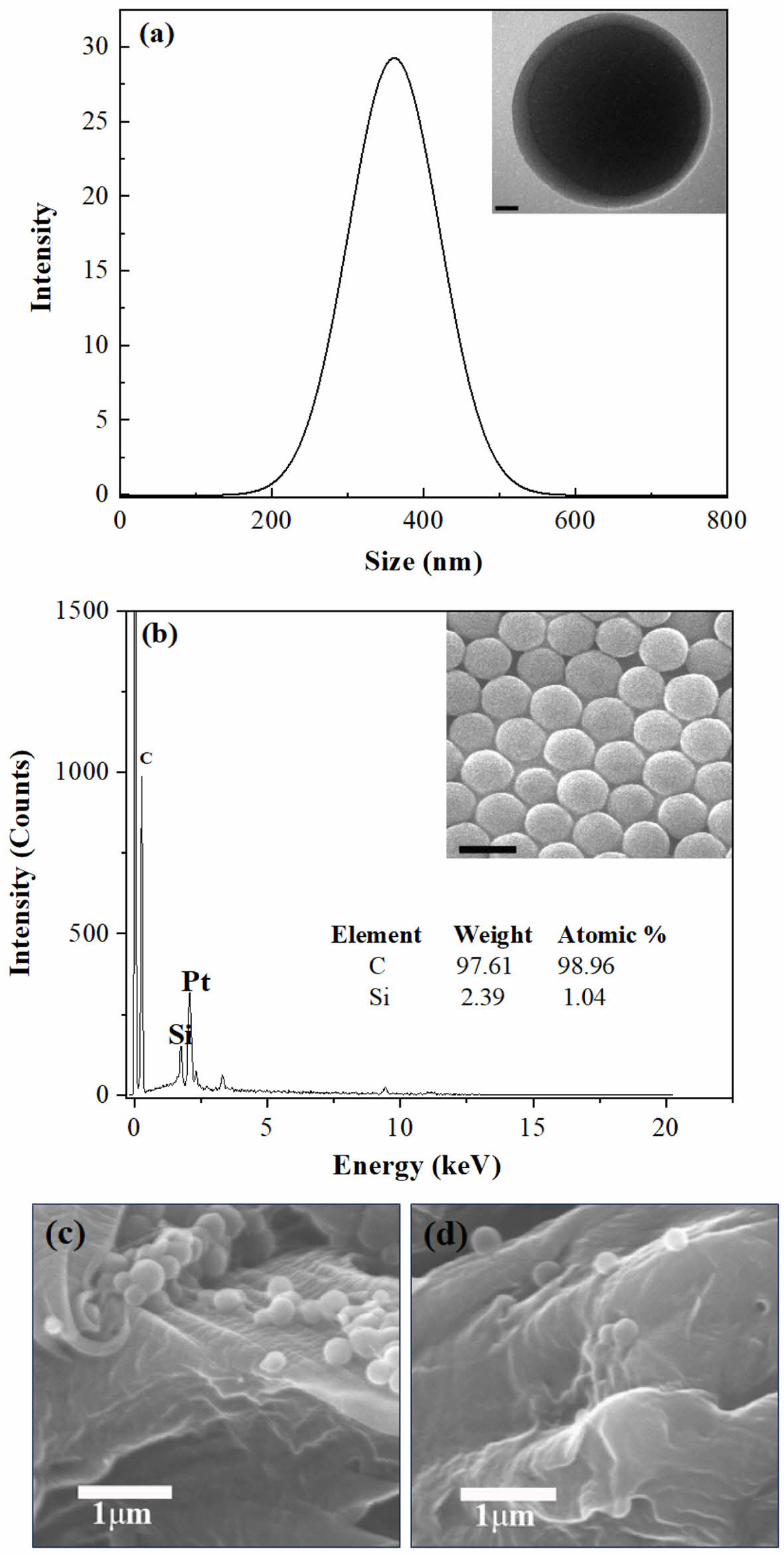

Morphology, Size and Elemental Analysis of SiOx/PS Nanoparticles. The core-shell structure of SiOx/PS nanoparticles was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2000 FxII, JEOL, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. Particle size distribution and the hydrodynamic diameter (Dh) were measured using particle size analyzer (SZ-100, Horiba, Kyoto, Japan) in accordance with ISO 22412: 2017. The surface morphology of the SiOx/PS nanoparticles were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Sirion 400, FEI Company, OR, USA) at 10.0 kV accelerating voltage at 12.0 mm working distance (WD) and × 0.3 k to × 15.0 k magnification. Elemental analysis of the nanoparticles was carried out by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX, EX-250 system, Horiba 7021-H, Kyoto, Japan) to confirm the presence of characteristic peaks corresponding to silicon (Si) and carbon (C).

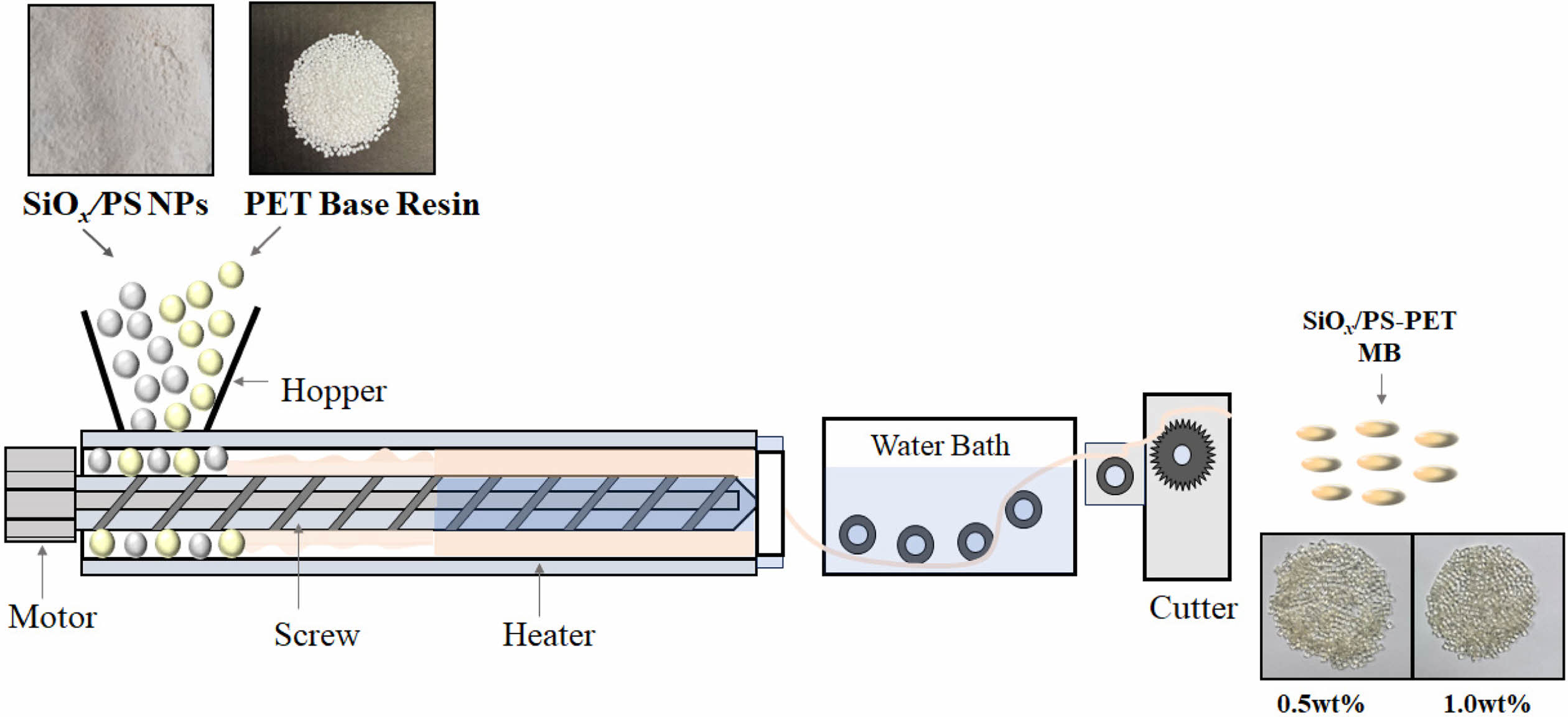

SiOx/PS-PET Nanocomposite Preparation. Two types of master pellets were prepared by incorporating 0.5 wt% and 1.0 wt% of SiOx/PS nanoparticles into the PET base resin via melt compounding. These master pellets were subsequently blended with additional PET base resin to obtain SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites with final concentrations of 2.0 wt% (0.5-2.0 wt% and 1.0-2.0 wt%) and 4.0 wt% (0.5-4.0 wt% and 1.0-4.0 wt%), respectively. PET resin with an intrinsic viscosity (IV) of 0.76 dL/g and a density of 1.40 ± 0.01 g/cm3 was dried at 100 ℃ for 12 h to minimize hydrolytic degradation prior to the blending process. SiOx/PS nanoparticles were added to PET base resin to produce a pelletized functional masterbatch as follows. First, a mixture of PET base resin and SiOx/PS nanoparticles was blended with a lubricant (LicoWax E, Clariant, Basel, Switzerland), a hydrolytically stable processing agent (Irgafos 168, Ciba Inc., Basel, Switzerland) and a thermal stabilizer antioxidant (Irganox 1010, Ciba Inc., Basel, Switzerland) at 400 rpm for 60 sec in a mixing jar. Subsequently, an anti-hydrolysis agent (ZIKA-AH 362, Ziko, Korea) was added to the mixture. The final blend was then processed via melt compounding using a twin-screw extruder (TEK 30, SM Platek, Korea, d = 30 mm, L/D = 40) at 210 ℃ with a screw speed of 160 rpm (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Representation of the melt extrusion process used to fabricate SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites master batch (MB) pellets.

Thermal Characterization. Thermal characterization was performed using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC 204 F1 Phoenix, NETZSCH, Bavaria, Germany) with approximately 6 mg samples. Each sample was heated from 0 to 280 ℃ at a heating rate of 10 ℃/min to remove the

thermal history. The sample was then cooled to 0 ℃ at the rate of 10 ℃/min and reheated to 280 ℃. All measurements were carried out under a nitrogen (N2) atmosphere. The thermal and crystallization parameters were obtained from the heating (Tm, maximum of endothermic melting peak) and cooling scans (Tc, exothermic peak of crystallization).

The heat of fusion (ΔHf) and crystallization heat (ΔHc) were determined from the areas under the melting and crystallization peaks, respectively, and were normalized per gram of each sample. The degree of crystallinity (Xc) was obtained from equation 2:21

where ΔHfis the enthalpy of fusion, ΔHc is the enthalpy of crystallization and DHh0 is the heat of fusion of 100% crystalline PET, which is 115 J/g.22

Mechanical Testing. Dogbone-shaped specimens for tensile testing and notched specimens for impact testing were prepared using an injection molding machine (HiCom 700, LG, Korea). Five replicate specimens were used for each condition. Tensile testing was conducted using a universal testing machine (MTS 858 Bionix II, 25kN load cell, MN, USA) in accordance with ASTM D638 at room temperature with a crosshead speed of 0.2 mm/s. Data were acquired at 0.1 s intervals with a sampling frequency of 10 Hz. Young’s modulus, yield strength, tensile strength, and elongation at break were determined from the stress-strain curves. The results were averaged, and standard deviations were calculated to assess repeatability. A one-tailed t-test was performed in Microsoft Excel at a 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) to evaluate statistical significance. Izod impact strength was measured in accordance with ASTM D256-10 using an impact tester (DG-UB, Toyoseiki, Tokyo, Japan), and the energy absorbed during fracture was recorded in joules per meter (J/m).

Blowing Process for the SiOx/PS-PET Bottles.Transparent PET bottles were manufactured using a standard injection stretch blow molding process. Pelletized functional masterbatch containing 0.5 wt% and 1.0 wt% of SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites were mixed with PET base resin using a volumetric feeder (Smart Color II, Boo Heung Eng Co., LTD, Kyunggi, Korea), mounted directly onto the hopper of an injection molding machine. After blending, preforms were fabricated via injection molding, followed by biaxial stretch blow molding to produce the final bottle shape. The mold temperature was set at 280 ℃ (Aoki Technical Laboratory, Inc., Nagano-ken, Japan). Transparent bottles with a storage capacity of 100 mL were obtained and subsequently used for oxygen transmission rate testing.

Stress Relaxation, Rheological and Barrier Property Measurement. Stress relaxation measurements were carried out using an MCR 702 multidrive rheometer (Anton Paar, Buchs, Switzerland) at 260 ℃ under 10% strain. The relaxation modulus G(t) was recorded over a duration of 1000 s. The stress decay over time was recorded, and the obtained data were normalized against stress at t = 0.01 s and demonstrated power-law dependence, σ(t)/σ(0) = At-b. The fitting constants, A and b, were derived from the power law analysis. The rheological properties of pelletized SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites were investigated using a plate-type rheometer (MCR 702, Anton Paar, Austria) equipped with 25 mm parallel plates and a 1 mm gap. A frequency sweep test was conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere at 260 ℃ and 5% strain, covering an angular frequency range of 500 to 1 rad/s within the viscoelastic region. Oxygen transmission rate (OTR) was measured to evaluate the oxygen barrier performance of PET bottles fabricated from pristine and SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites. The test was carried out using OX-TRAN Model 2/61 (MOCON, USA) in accordance with ASTM F1307-20. Three bottles per sample group were randomly chosen, and O2 levels were monitored continuously over a 24 h period.

Morphology and SiOx/PS Nanocomposite Characterization. The morphology, size distribution, and composition of the synthesized SiOx/PS nanoparticles were examined using TEM, DLS, SEM and EDAX analyses, as shown in Figure 1. A narrow and symmetric particle size distribution centered around ~340 nm was observed, with a hydrodynamic diameter (Dh) of approximately 340 nm for the SiOx/PS nanoparticles, indicating uniform particle formation and well-controlled size uniformity in the colloidal dispersion. A spherical and well-defined core-shell structure of the SiOx/PS nanoparticles was confirmed by TEM. The darker central region corresponds to the SiOx(silicate compound)core, which was uniformly encapsulated within a lighter peripheral region attributed to the polystyrene (PS) shell (Figure 1(a), inset).23,24

The surface morphology of prepared SiOx/PS nanoparticles was examined by SEM, which revealed highly uniform spherical particles with good monodispersity (Figure 1(b), inset). The elemental composition spectra of the SiOx/PS nanoparticles revealed characteristic peaks at 0.2 keV, 1.71 keV, and 2.05 keV, which were assigned to carbon (C), silicon (Si), and platinum (Pt), respectively (Figure 1(b)). The dominant C peak was attributed to the PS shell, surrounding the SiOxcore. A small Pt peak, originating from the sputter coating used for TEM sample preparation, was also detected. The presence of a distinct Si peak in the selected area confirmed the incorporation of the silicate compound within the polymeric shell.

The quantified EDAX spectrum (Figure 1(b), inset table), revealed that carbon was the dominant element, accounting for 98.96 atomic %, while silicon element contributed 1.04 atomic %. The Si peak at 1.74 keV further confirmed the presence of the silica component and supported the encapsulation of SiOxcores within the polystyrene shell. The combination of spherical morphology, core-shell structure, and Si peak confirmed successful SiOx/PS nanoparticle fabrication.

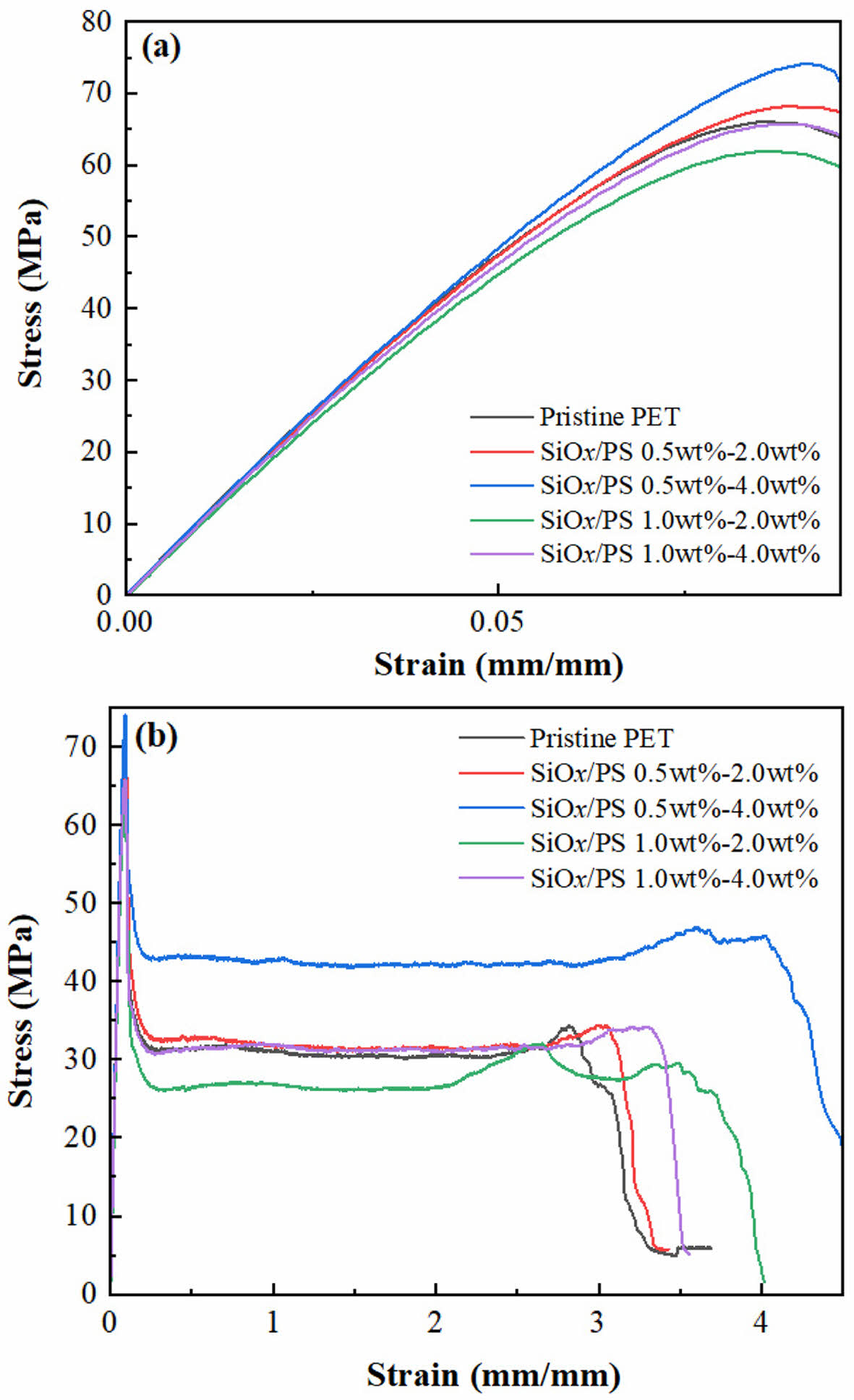

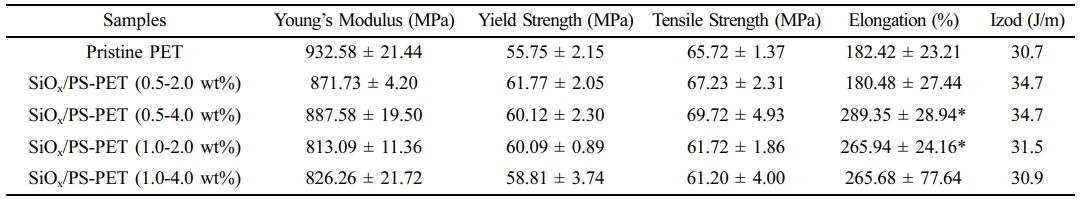

Characterization of Mechanical Properties. The incorporation of SiOx/PS nanoparticles into pristine PET resulted in enhanced mechanical properties, including tensile strength, yield strength, elongation, and Izod impact strength, whereas Young’s modulus decreased, as shown in Table 1. The stress-strain curves (Figure 2(a)) show an initial linear region corresponding to elastic deformation, in which PET exhibited viscoelastic behavior. The concentration of SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites affected both the strength and fracture characteristics.

Pristine PET exhibited a brittle-like fracture with a

rapid stress drops after the ultimate tensile strength, indicating limited plastic deformation prior to fracture. In contrast, 0.5-4.0 wt% SiOx/PS-PET samples showed enhanced toughness, evidenced by an extended plastic region and higher fracture resistance. This behavior indicated efficient stress transfer from the PET matrix to well-dispersed SiOx/PS nanoparticles. The 0.5-4.0 wt% loading condition exhibited the greatest increases in tensile strength and Young’s modulus, indicating effective reinforcement and improved stiffness. Other loadings (0.5-2.0 wt% and 1.0-4.0 wt%) showed only moderate improvements, while the 1.0-2.0 wt% loading exhibited decreased performance, likely due to nanoparticle aggregation, which serves as a stress concentration site and disrupts polymer chain mobility, thereby reducing overall mechanical reinforcement.

The PET sample prepared with 0.5 wt% masterbatch showed increased Izod impact strength, with the highest value (34.7 J/m) observed at 0.5-2.0 wt% and 0.5-4.0 wt% loadings. This improvement was attributed to effective reinforcement of the PET matrix by the SiOx/PS nanoparticles, which enhanced toughness and energy absorption during impact. This

observation is consistent with previous studies reporting that well-dispersed nanofillers facilitate efficient stress transfer and enhance impact resistance.25 At higher loadings (1.0-2.0 wt%: 31.5 J/m, 1.0-4.0 wt%: 30.9 J/m), only moderate improvement in impact strength was observed, likely due to

agglomeration, which reduced energy dissipation efficiency within the PET matrix.

Increased crystallinity, which induces a more rigid internal structure could have contributed to the enhanced toughness and energy dissipation capability of the PET. The yield strength of pristine PET (55.75 ± 2.15 MPa) increased significantly to 61.77 ± 2.05 MPa and 60.12 ± 2.30 MPa for the 0.5-2.0 wt% and 0.5-4.0 wt% loadings, respectively, suggesting uniform nanoparticle dispersion within the PET matrix and

effective reinforcement. This enhancement likely improved interfacial adhesion and stress transfer efficiency between polymer chains, as previously reported.26

Elongation at break also increased by showing a 58.6% increase in the 0.5-4.0 wt% samples compared to pristine PET, which is attributed to enhanced polymer chain mobility and greater ductility resulting from the homogeneously dispersed SiOx/PS nanoparticles (Figure 2(b)). At higher loadings (1.0- 2.0 wt% and 1.0-4.0 wt%), elongation slightly decreased, likely due to aggregation, which restricted polymer chain motion and limited ductility enhancement. These results indicated that optimal nanoparticle loading enhances elasticity and toughness of PET matrices by enabling more uniform stress redistribution throughout the PET structure.27,28

The Young’s modulus of SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites decreased, reaching the lowest value (813.09 ± 11.36 MPa) at 1.0-2.0 wt%. This behavior was attributed to a plasticizing effect, which increased polymer chain mobility and reduced the brittleness of PET.29 The concurrent increase in elongation and decrease in modulus reflected improved flexibility, a desirable property in applications requiring toughness.

The highest tensile strength (69.72 ± 4.93 MPa), 6.1% greater than that of pristine PET, was observed at a 0.5-4.0 wt% loading. In contrast, higher loadings (1.0-2.0 wt% and 1.0-4.0 wt%) exhibited reduced tensile strength, likely due to aggregation, which functioned as a stress concentration site and disrupted stress transfer efficiency, as previously reported.30 Overall, the 0.5-4.0 wt% loading provided the most significant mechanical improvements, achieving the highest tensile strength (69.72 MPa)andelongation at break (289.35%), which are attributed to homogeneous dispersion and polymer chain reorganization via strong nanoparticle-polymer interactions.31

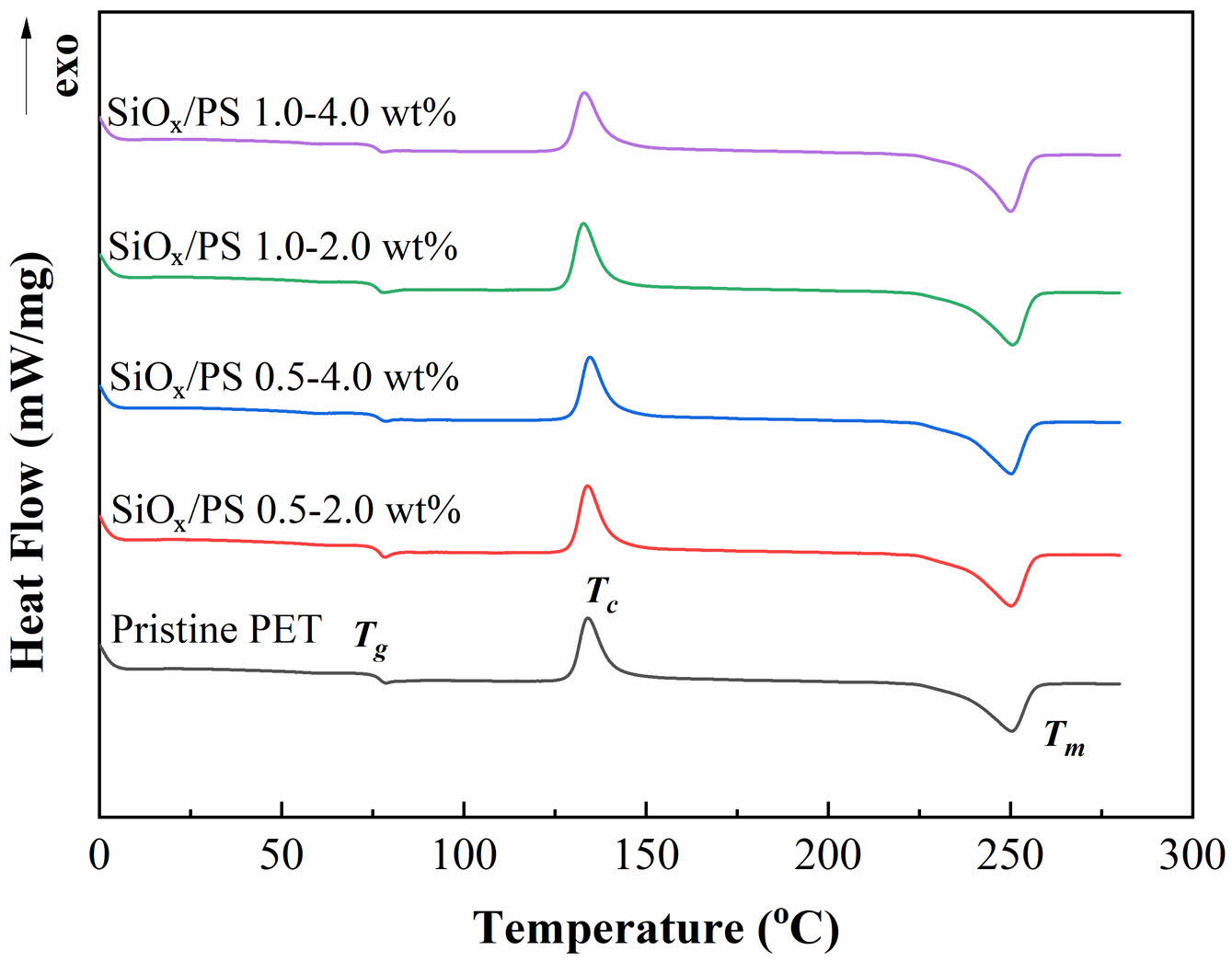

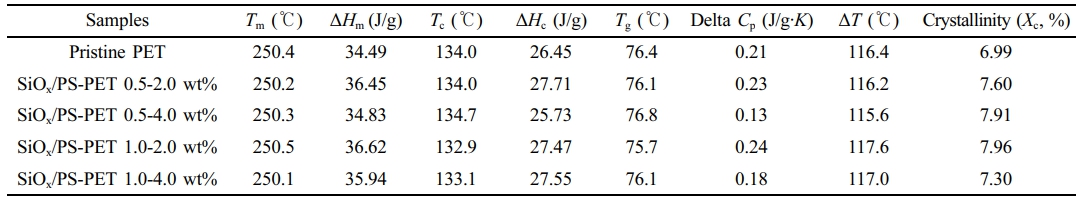

Thermal Characterization. The thermal properties of pristine PET and PET blended with SiOx/PS nanoparticles exhibited characteristic thermal transitions during the cooling and heating cycles, as shown in Figure 3. The glass transition temperature (Tg) of pristine PET was 76.4 ℃, consistent with previously reported values of 67 ℃ for amorphous PET and 81 ℃ for semi-crystalline PET.32 The Tg of the 0.5-4.0 wt% loading increased slightly to 76.8 ℃, suggesting enhanced PET-SiOx/PS nanoparticle interactions due to homogeneous dispersion, which was likely promoted by the polystyrene shell surrounding the rigid SiOxcore, facilitating interfacial adhesion between PET chains and nanoparticles.

This Tg increase correlated with the enhanced crystallinity of SiOx/PS-PET (Table 2), which is attributed to the functional role of SiOx/PS nanoparticles as nucleation sites that promote PET crystallization. As previously reported, increased crystallinity elevates Tg by restricting polymer chain mobility near crystallites.33 At higher loadings (1.0-2.0 wt% and 1.0-4.0 wt%), Tg decreased slightly, likely due to nanoparticle agglomeration, which reduced the extent of chain mobility restriction within the amorphous regions and led to less effective structural modulation of PET internal structure.34 The endothermal melting peak (Tm) remained relatively unchanged across all samples, ranging from 250.1 ℃ (1.0-4.0 wt%) to 250.5 ℃ (pristine PET) as shown in Table 2. A Tm shift toward a higher value is typically associated with the formation of more rigid crystalline networks, which were not significantly formed at the tested loading levels.35

The crystallization temperature (Tc) of pristine PET (134.0 ℃) increased slightly to 134.7 ℃ at the 0.5-4.0 wt% loadings, suggesting accelerated crystallization during cooling due to a nucleation effect from homogeneous nanoparticle dispersion.33 At these nucleation sites, the high surface area of nanoparticles facilitated interactions with PET, reducing chain entanglement and enhancing molecular alignment, thereby promoting crystallization at higher

temperatures. At higher loadings (1.0-2.0 wt% and 1.0-4.0 wt%) aggregation diminished these effects, reducing the available nucleation surface and shifting

Tc toward lower temperatures (Figure 3).

The increase in Tc was also associated with enhanced crystallinity of the polymer matrix through a more ordered molecular structure, which limited gas molecule diffusion and contribute to improved barrier performance.36 Crystallinity (Xc), calculated using Equation 2, increased from 6.99% (pristine PET) to 7.96% (1.0-2.0 wt%), supported by increased heat of fusion (ΔHf) and crystallization heat (ΔHc) (Table 2). At the highest loading (1.0-4.0 wt%), Xc decreased slightly, though still higher than that of pristine PET, likely due to nanoparticle aggregation disrupting dispersion.

The degree of supercooling (ΔT = Tm-Tc) was used to evaluate crystallization kinetics. A smaller ΔT indicates enhanced crystallization ability.37-39 The lowest ΔT (115.6 ℃) observed at 0.5-4.0 wt% loading confirms effective nucleation by well-dispersed SiOx/PS nanoparticles within the PET matrix. At higher loadings, ΔT increased to 117.6 ℃ (1.0-2.0 wt%) and 117.0 ℃ (1.0-4.0 wt%), suggesting reduced nucleation efficiency due to aggregation from excessive nanoparticle loading. These findings indicate that optimal nanoparticle loading promotes nucleation, increases crystallinity, and enhances thermal properties by restricting polymer chain mobility.

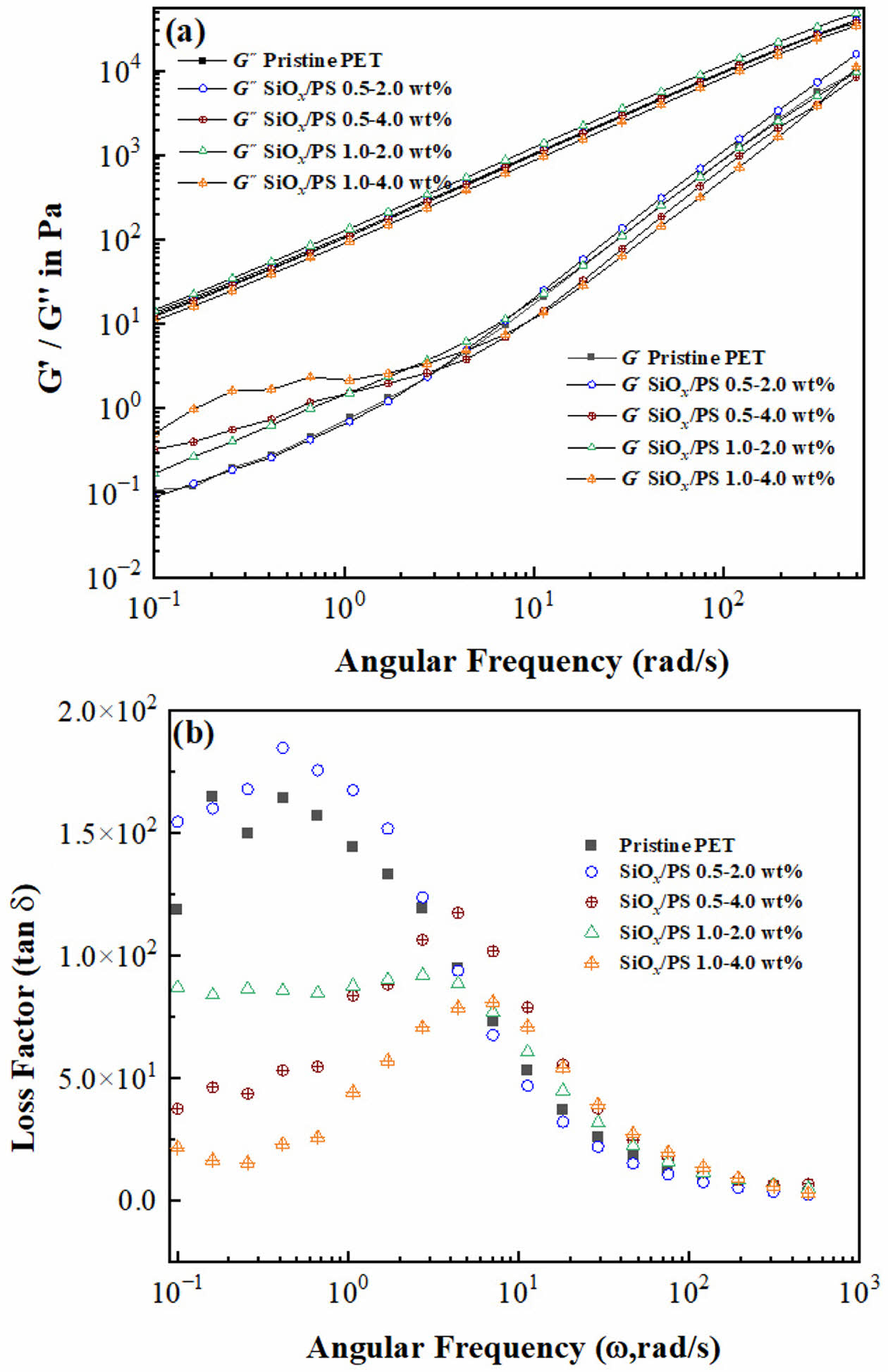

Rheological Properties. The effect of nanoparticle incorporation on viscoelastic properties was evaluated through frequency sweep tests, as shown in Figure 4. Both the storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G") increased moderately with frequency, showing G" consistently higher than G'. G' increased continuously and approached G'', but no cross-over point (G"/G'=1) was observed (Figure 4(a)). Notably, G' increased at 0.5-4.0 wt%, 1.0-2.0 wt% and 1.0-4.0 wt%, particularly in the low-frequency region, indicating restricted polymer chain mobility due to nanoparticle reinforcement. In contrast, G' at 0.5-2.0 wt% was comparable to pristine PET, suggesting limited reinforcement at this lower concentration.

At intermediate frequencies (ω~101 rad/s), a slight decrease in G' was observed for the 0.5-4.0 wt% and 1.0-4.0 wt% samples, likely due to relaxation or transient disruption of the nanoparticle-polymer network. At high frequencies, G' values converged with those of pristine PET, indicting reduced nanoparticle-polymer interactions and a similar viscoelastic response in both filled and unfilled polymer systems under short relaxation times.40

In polymer-nanocomposites, the terminal zone slope follows a power-law dependence (G' ∝wn), where a decreasing exponent n indicates a transition toward more elastic, solid-like behavior. A fully relaxed polymer melt shows a liquid-like response (G' ∝w2), whereas restricted relaxation due to entanglements or nanoparticle-polymer interactions shifts toward a more solid-like behavior (G' ∝w0).41 The exponent n for pristine PET (G' ~ω0.79) decreased to G'~ω0.67 at 0.5-4.0 wt%, indicating enhanced elasticity and transition toward solid-like behavior due to well-dispersed nanoparticles and restricted chain mobility.42

In contrast, higher exponents were obtained for the 0.5-2.0 wt% (G' ~ ω0.82) and 1.0-2.0 wt% (G' ~ ω0.94) samples, suggesting fluid-like behavior. This was attributed to poor nanoparticle dispersion, which reduced effective surface area available for interaction with polymer chains, leading to ineffective stress transfer and a less uniform polymer matrix.43The exponent at 1.0-4.0 wt% (G'~ω0.76) was similar to that of pristine PET, implying that aggregation at high loading limited network formation and reinforcement efficiency. The presence of aggregation appeared as cluster-like morphology within the PET matrix whereas well-dispersed individual particles with minimal were observed at lower loading levels (Figure 1(c) and (d)). These results highlight that optimal nanoparticle loading and dispersion at 0.5-4.0 wt% enhance solid-like behavior through effective nanoparticle-polymer interactions

Figure 4(b) presents the loss factor (tan δ, Gʺ/G') as a function of angular frequency. All samples showed tan δ peaks at intermediate frequencies, followed by a decrease at higher frequencies, where values converged consistent with the expected viscous-to-elastic transition.44 At low frequency (ω < 100 rad/s), pristine PET and 0.5-2.0 wt% sample exhibited higher tan δ values, indicating greater viscous behavior of a relaxed polymer system due to insufficient SiOx/PS nanoparticle concentration for effective reinforcement.45 In contrast, 0.5-4.0 wt%, 1.0-2.0 wt% and 1.0-4.0 wt% samples exhibited reduced tan δ values, reflecting increased G' and stronger polymer-SiOx/PS nanoparticle interactions that restricted chain mobility. The shift of tan δ peaks toward higher frequencies (ω ~ 101 rad/s) with increasing SiOx/PS nanoparticle loading suggests retarded relaxation and more solid-like behavior due to improved interfacial interactions.46 These findings confirm that both nanoparticle concentration and dispersion are critical parameters for regulating viscoelastic performance and enhancing reinforcement in SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposite.

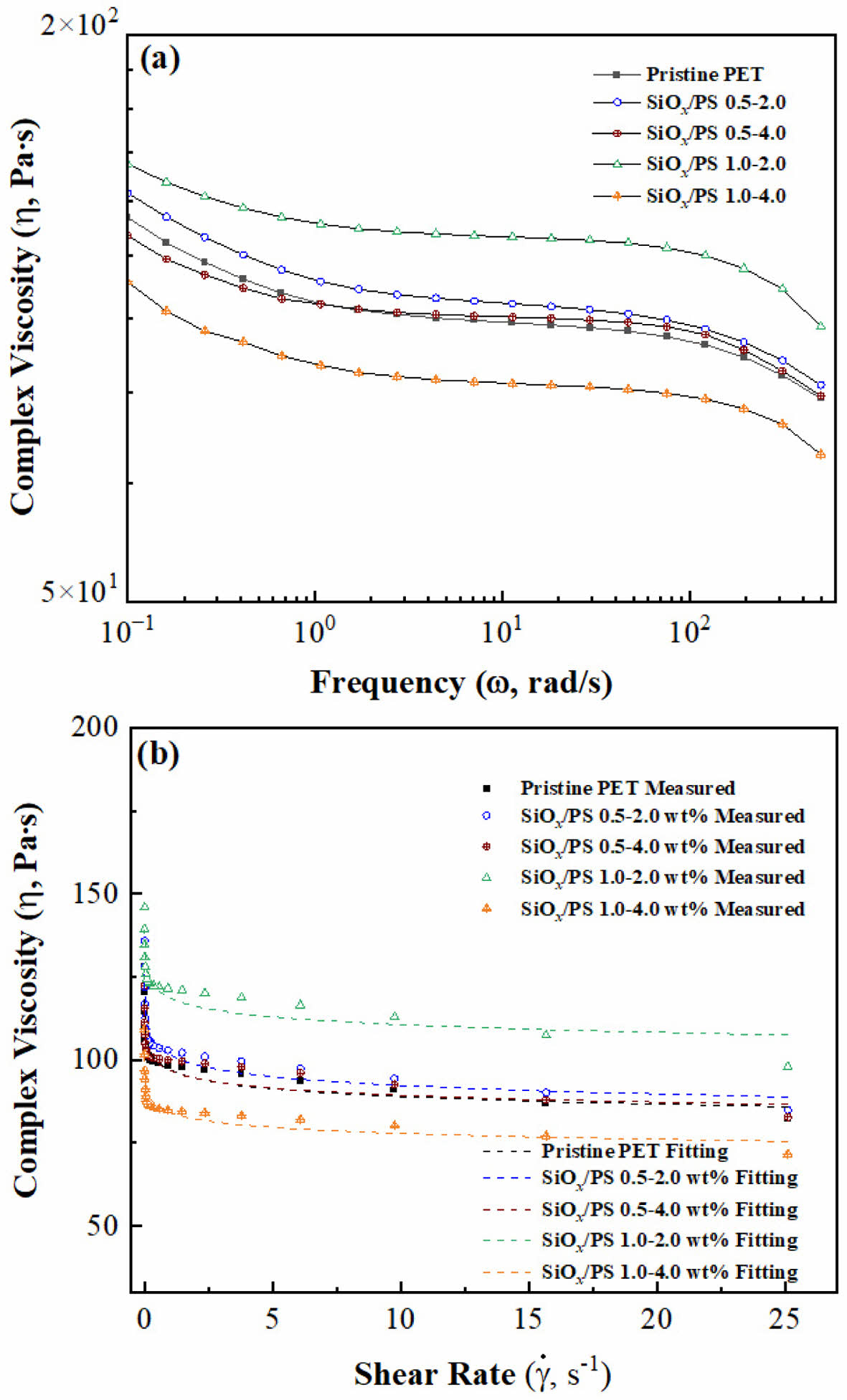

Complex Viscosity Measurement. The incorporation of SiOx/PS nanoparticles into the polymer matrix significantly influences the complex viscosities (η), depending on the loading concentration, as shown in Figure 5(a). Both pristine PET and nanocomposites exhibited a decrease in η with increasing frequency, characteristic of non-Newtonian shear-thinning behavior commonly observed in polymeric systems. This behavior is attributed to polymer chain disentanglement and nanoparticle-polymer interactions, which affect the overall viscoelastic response.41,47 The 0.5-2.0 wt% and 1.0-2.0 wt% samples showed consistently higher η values than pristine PET across all frequency regions, indicating increased resistance of the polymer melt to flow due to enhanced polymer-nanoparticle interactions. This suggests that well-dispersed SiOx/PS nanoparticles restricted chain mobility and effectively reinforced the polymer matrix.48 The 0.5-4.0 wt% sample showed moderate viscosity enhancement, with a slight reduction in η around ω ~ 100 rad/s followed by recovery at higher frequencies, indicating limited reinforcement‐ not as effective as that of the 1.0-2.0 wt% sample.

The 1.0-2.0 wt% formulation exhibited the highest η values, suggesting strong polymer-nanoparticle interactions and effective reinforcement, likely due to

homogeneous dispersion.

Conversely, the highest loading (1.0-4.0 wt%) resulted in the lowest η values, suggesting that aggregation or phase separation reduced the reinforcement effect. These changes are closely related to reduced entanglement density and restricted polymer chain mobility. As previously reported, optimal nanoparticle dispersion enhances η, whereas excessive loading causes structural defects that diminish reinforcement efficiency.41

From a polymer flow perspective, the increase in η reflects greater resistance of the polymer to flow, attributed to restricted polymer chain mobility caused by a secondary network structure formed via particle-particle or particle-polymer interactions within the PET matrix.49,50

As shown in Figure 5(b), η as a function of shear rate (γ́) followed a power-law fluid model, with good agreement between experimental data and fitted curves, thereby confirming the reliability of the rheological measurements. The observed decrease in η with increasing shear rate confirms shear-thinning behavior, characteristic of polymer melts and nanocomposites due to chain disentanglement.51 At a shear rate near 5 s-1, a significant drop in η was observed, followed by a monotonic decrease at higher shear rates due to the disruption of polymer-nanoparticle interactions.

The dispersion state of SiOx/PS nanoparticles critically influenced PET flow dynamics. At low shear rates, the nanoparticles remained well-integrated in the polymer matrix, maintaining a certain level of resistance to flow. As shear rate increased, nanoparticle dispersion improved, allowing polymer chain disentanglement and alignment in the shear direction, which reduces resistance to flow and promotes steady-state viscosity. This further reduction in η is characteristic of shear flow in polymer melts, where nanoparticle-induced network structures formed at low shear rates experience disintegration at high shear rates, thereby reducing η.52

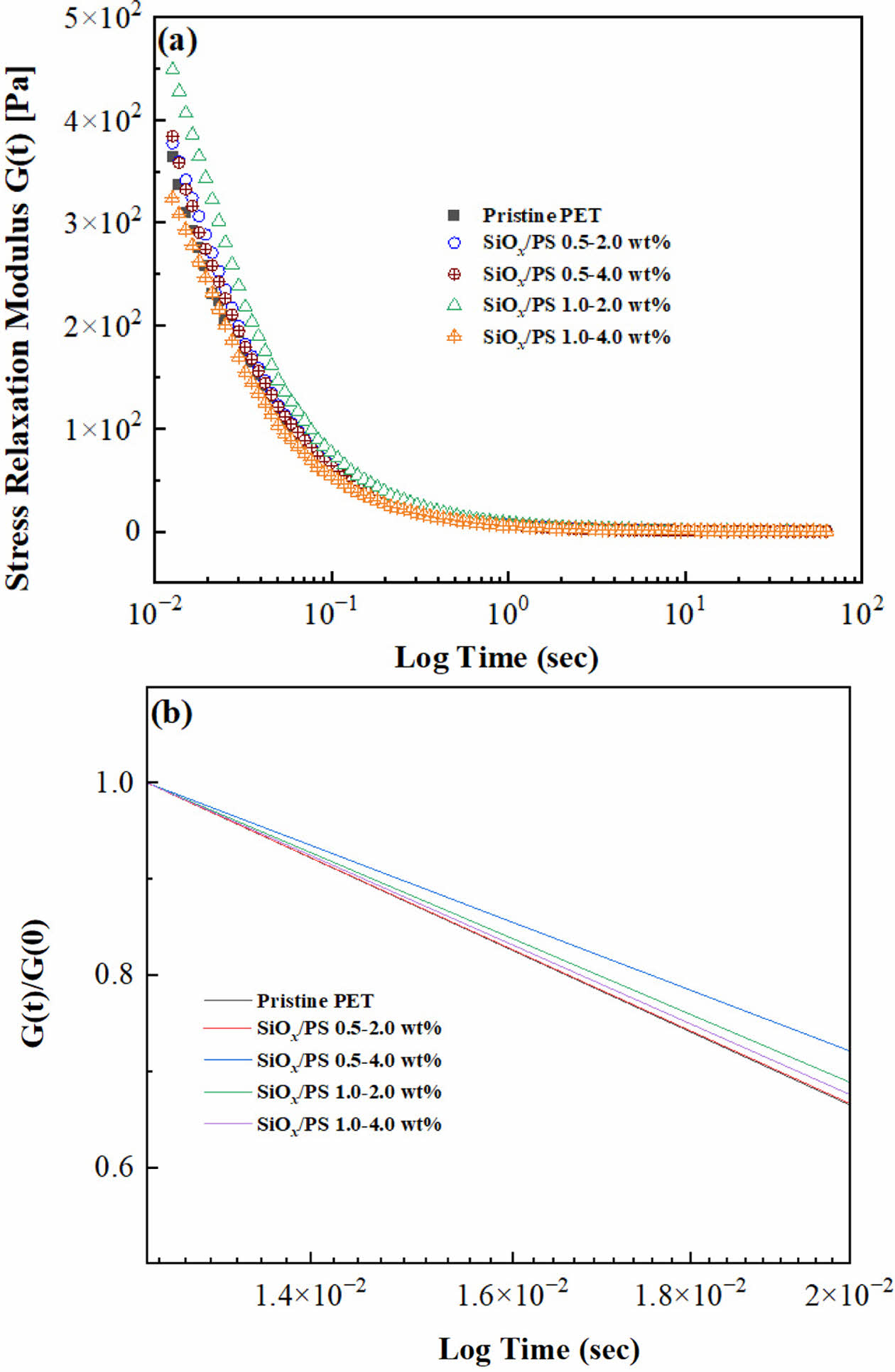

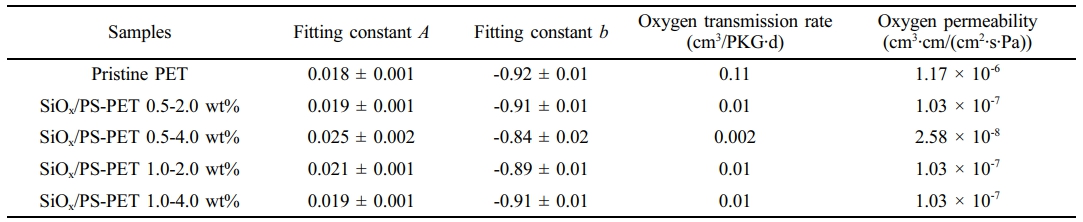

Stress Relaxation Test. The stress relaxation test performed at 10% strain exhibited a gradual decrease in relaxation modulus (G(t)) over time, eventually reaching a plateau, indicating viscoelastic behavior. As shown in Figure 6(a), the SiOx/PS nanoparticle loadings influenced the relaxation behavior and reinforcement efficiency. The 1.0-2.0 wt% sample exhibited the highest relaxation modulus (G(t)), indicating more restricted polymer chain mobility due to strong polymer-nanoparticle interactions facilitated by uniform dispersion.

In contrast, the 0.5-2.0 wt% and 1.0-2.0 wt% samples showed little difference from pristine PET, suggesting limited reinforcement at lower concentrations. The highest loading (1.0-4.0 wt%) resulted in a lower G(t) than pristine PET, likely due to nanoparticle aggregation, which reduced reinforcement effectiveness.

The fitting constants A and b were obtained via power-law analysis to determine the slope steepness in the log-log stress relaxation curve (Figure 6(b)). The 0.5-4.0 wt%, 1.0-2.0 wt%, and 1.0-4.0 wt% samples exhibited lower slopes than pristine PET, indicating slower relaxation due to increased elasticity.

The reduced slope, i.e., a less steep relaxation curve, reflects restricted chain mobility and improved load transfer between the PET matrix due to well-dispersed nanoparticles. Among all samples, the 0.5-4.0 wt% sample showed the slowest slope decay, indicating delayed relaxation and enhanced elastic behavior. Conversely, the 0.5-2.0 wt% sample showed a slope similar to pristine PET, suggesting limited reinforcement (Table 3).

In polymer-nanocomposite, stress relaxation rate depends on chain disentanglement and interfacial slippage, both influenced by nanoparticle dispersion and interparticle interactions.53,54

At optimal loading, well-dispersed SiOx/PS nanoparticles restrict chain mobility through effective interaction with PET chains, reducing stress over time and delaying relaxation rate, as observed in the 0.5-4.0 wt% formulation. In contrast, the rapid relaxation at 1.0-4.0 wt% reflects insufficient elastic network formation due to aggregation. This delayed stress relaxation at optimal loading (0.5-4.0 wt%) correlates with increase in Young’s modulus, indicating enhanced elastic stiffness, and strong polymer-nanoparticle interactions.

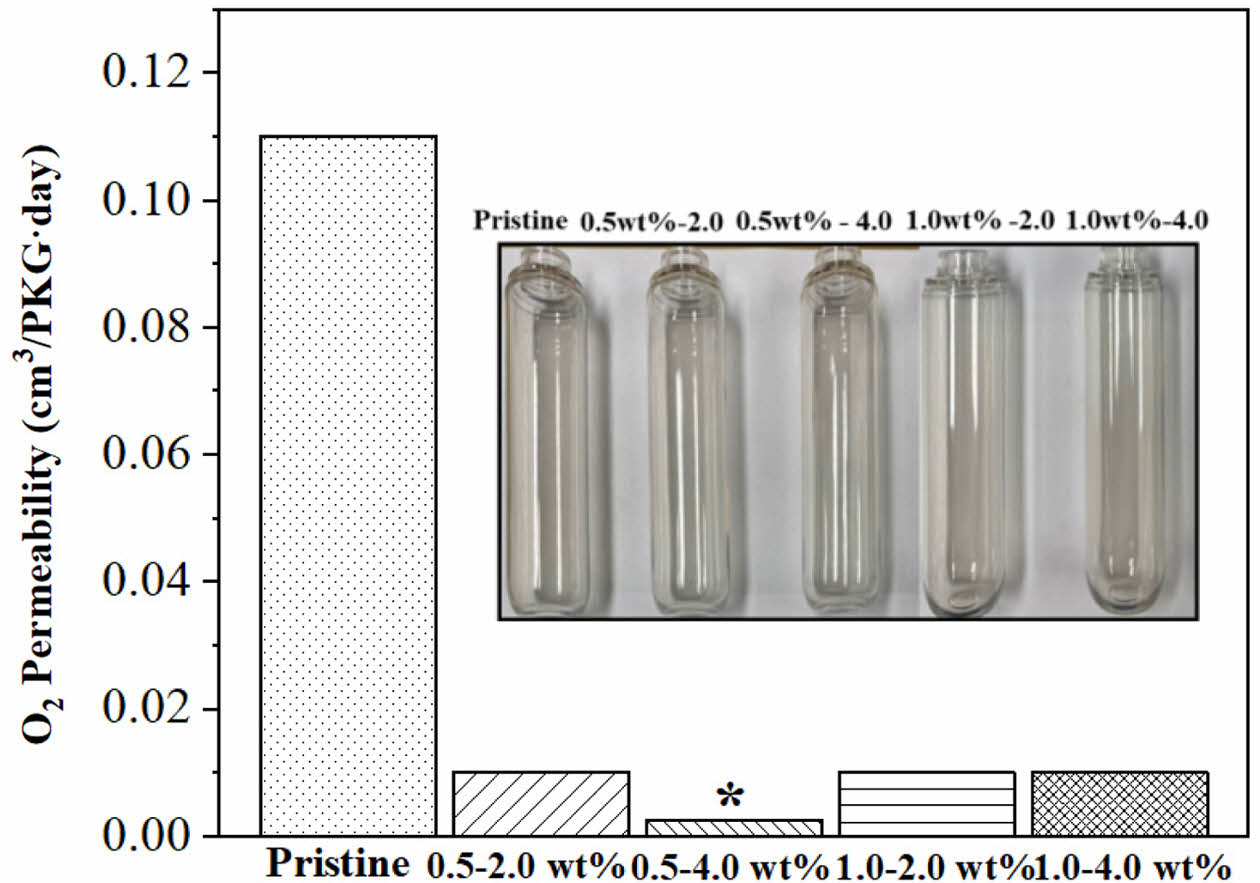

Barrier Properties.The barrier property of the PET bottles was evaluated based on the oxygen transmission rate (OTR), a key parameter for assessing gas barrier performance, and was found to vary with the SiOx/PS nanoparticle loading concentration, as shown in Figure 7. The incorporation of SiOx/PS nanoparticles significantly reduced the OTR values, exhibiting a 98.2% decrease at the 0.5-4.0 wt% loading, from 0.11 cm3/PKG∙d (pristine) to 0.002 cm3/PKG∙d (Table 3). Other SiOx/PS-PET bottles showed a 91% decrease, with OTR values reaching 0.01 cm3/PKG∙d compared to the pristine PET bottle. This decrease in OTR values was consistent with previous studies, in which the incorporation of organoclay into the PET matrix induced a 27% reduction in O2 permeability by influencing polymer chain mobility and enhancing gas barrier properties.55

Oxygen permeability is influenced by several factors such as polymer matrix composition, filler incorporation, and processing conditions. The SiOx/PS nanoparticle incorporation effectively enhanced oxygen barrier properties, exhibiting a significant decrease in O2 permeability across all tested loading concentrations. As shown in Table 3, the 0.5-4.0 wt% sample decreased by two orders of magnitude compared to pristine PET bottle, while other loadings exhibited a one order of magnitude reduction.

Among all formulations, the 0.5-4.0 wt% PET bottles exhibited the most enhanced barrier performance, which is likely attributed to stronger reinforcement between the SiOx/PS nanoparticles and the PET matrix through homogeneous nanoparticle dispersion, as reported previously.56 The improved oxygen barrier property was also associated with increased crystallinity, enhanced elastic stiffness, and the transition to a more solid-like viscoelastic response at the loading concentration. SiOx/PS nanoparticles may also act as nucleating agents, promote crystallization and restrict polymer chain mobility, both of which contribute to reduced oxygen permeability. A similar mechanism was observed by Choi et al., in which the incorporation of graphene oxide nanoparticles in PVA (polyvinyl alcohol) increased crystallinity and decreased oxygen permeability due to nucleating effect.57

From a diffusion perspective, nanoparticles are known to create more tortuous paths that effectively hinder oxygen molecule transport. Gas molecule diffusion in polymers occurs through interconnected voids in the polymer matrix, forming a continuous permeation pathway that is influenced by the size and distribution of the voids. Our results suggest that homogeneous dispersion of SiOx/PS nanoparticles, particularly up to 1.0-2.0 wt% loading, effectively restricted chain mobility, thereby suppressing the free movement of oxygen molecules. At high concentrations (1.0 - 4.0 wt%), aggregation may partially reduce available free-volume and physically block O2 molecule diffusion in the PET matrix. Choudalakis et al. reported that nanoparticle incorporation into polymer matrix reduces free volume by introducing high surface area and minimizing hole radius.58 Additionally, nanoparticle dispersion in polymer matrix was found to inhibit the formation of new voids by limiting polymer segmental motion and subsequent rearrangement. These results clearly demonstrate that the incorporation of SiOx/PS nanoparticles into the PET significantly improved its oxygen barrier property, as evidenced by up to 98% reduction in OTR and permeability values.

|

Figure 1 Morphological, dimensional, and compositional characterization of SiOx/PS nanoparticles: (a) particle size distribution obtained by DLS, with the inset showing a TEM image of a single core-shell structured SiOx/PS nanoparticle (scale bar: 20 nm); (b) EDAX spectrum confirming elemental composition, with the inset showing an SEM image revealing the uniform spherical morphology of the SiOx/PS nanoparticles (scale bar: 500 nm); (c) SEM image showing well-dispersed SiOx/PS nanoparticles within PET matrix; (d) higher nanoparticle loading resulted in aggregation formation within PET matrix. |

|

Figure 2 Stress-strain behavior of pristine PET and SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites at various nanoparticles loadings: (a) Stress-strain curves focusing on the elastic regions for pristine PET and nanocomposites. nanoparticle dispersion within the PET matrix and effective reinforcement; (b) Full-scale stress-strain curves showing differences in mechanical properties, including tensile strength and elongation. |

|

Figure 3 DSC thermogram of pristine PET and SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposite at different nanoparticle loadings, showing the glass transition temperature (Tg), crystallization temperature (Tc), and endothermal melting peak (Tm). |

|

Figure 4 Rheological properties of pristine PET and SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites at different nanoparticle loadings: (a) Storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G'') as a function of frequency (ω), showing enhanced viscoelastic response with increasing nanoparticle content; (b) Loss factor (tan δ) versus angular frequency (ω), indicating a decrease in damping behavior at higher frequency region for all samples. |

|

Figure 5 Complex viscosity (η) behavior of pristine PET and SiOx/ PS-PET nanocomposites at different loading conditions: (a) Complex viscosity (η) as a function of angular frequency (ω), showing shear-thinning behavior; (b) Complex viscosity (η) versus shear rate (γ́) of measured and power-law fitting plots, indicating reduced viscosity with increasing shear rate for all samples. |

|

Figure 6 tress relaxation behavior of pristine PET and SiOx/PSPET nanocomposites obtained at 10% strain: (a) Relaxation modulus G(t) as a function of time, showing a continuous decrease with increasing time; (b) Normalized relaxation modulus G(t)/G(0) plotted against time on a logarithmic scale, exhibiting power-law dependence for all samples. |

|

Figure 7 Oxygen permeability of pristine PET and SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites at various nanoparticle loadings. All nanocomposite formulations exhibited significantly reduced O2 permeability compared to pristine PET, indicating enhanced barrier performance. The inset shows representative images of transparent PET bottles manufactured for oxygen transmission test via stretch blow molding |

|

Table 1 Mechanical Properties of Pristine PET and SiOx/PS-PET Nanocomposites at Different Nanoparticle Loadings |

Values Represent Mean ± Standard Deviation (*p < 0.05) |

|

Table 2 Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Data of Pristine PET and SiOx/PS-PET Nanocomposites |

|

Table 3 Power-law Parameters (A and b) and Oxygen Permeability of Pristine PET and SiOx/PS-PET Nanocomposites |

The errors shown represent standard errors of mean |

In this study, the incorporation of SiOx/PS nanoparticles at 0.5-4.0 wt% loading into pristine PET resulted in significant improvements in thermal, mechanical, rheological, and barrier properties. Increases in crystallinity (Xc, 7.91%), Young’s modulus (887.58 ± 19.50 MPa), and storage modulus (G') along with a decrease in tan δ (Gʺ/G') across the frequency sweep range, were associated with a decrease in O2 permeability (0.002 cm3/PKG∙d).

These results indicate that the addition of SiOx/PS nanoparticles enhanced the stiffness and elastic character of the PET matrix, shifting its viscoelastic behavior toward a more solid-like response at higher frequencies due to stronger matrix-particle interactions and network formation. The SiOx/PS nanoparticles were successfully incorporated and uniformly dispersed within the PET matrix, acting as nucleating agents that lowered the energy barrier for crystallization and contributed to mechanical reinforcement. The observed reduction in O2 permeability was attributed to restricted polymer chain mobility and decreased free volume, highlighting the role of SiOx/PS nanoparticles in inhibiting gas diffusion through the reinforced PET structure. By achieving an optimal balance of nanoparticle dispersion, interfacial adhesion, and structural reinforcement, the SiOx/PS-PET nanocomposites present a promising strategy for enhancing the toughness, stiffness, and barrier performance of PET, making them suitable candidates for high-performance packaging and engineering applications.

- 1. Umamaheswari, S.; Murali, M. FTIR Spectroscopic Study of Fungal Degradation of Poly (ethylene terephthalate) and Polystyrene Foam. Elixir Chem Eng. 2013,64, 19159-19164.

- 2. Lee, Y.; Han, S.; Kim, Y. Investigation of Hydrophobic Properties of PSII-modified EVOHG, LLEPE, and PET Films. J. Surf. Anal. 2005,12,258-262.

- 3. Licciarlello, F.; Coriolani, C.; Muratore, G. Improvement of CO2 Retention of PET for Carbonated Soft Drinks. Ital. J. Food Sci.2011, 23,115-117.

- 4. Kráčalík, M.; Studenovský, M.; Mikešová, J.; Sikora, A.; Thomann, R.; Friedrich, C.; Fortelný, I.; Simoník, J. Recycled PET Nanocomposites Improved by Silanization of Organoclay. J. App. Polym. Sci. 2007, 106, 926-937.

-

- 5. Pattanayek, S. K. S.; Ghosh, K. A. Dynamic Shear Rheology of Colloidal Suspensions of Surface-Modified Silica Nanoparticles in PEG. J. Nanopart. Res. 2018,20,53.

-

- 6. Mohebbi, A.; Dehghani, M.; Mehrabani-Zeinabad. A. Study of Thermal and Rheological Behavior of Polystyrene/TiO2, Polystyrene/SiO2/TiO2 and Polystyrene/SiO2 Nanocomposites. Materials with Complex Behaviour II,Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 2012,573-582.

-

- 7. Lima, J.; Fitaroni, L.; Chiaretti, D.; Kaneko, M.; Cruz. S. Degradation Process of Low Molar Mass Poly(ethylene terephthalate)/Organically Modified Montmorillonite Nanocomposites: Effect on Structure, Rheological, and Thermal Behavior. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater.2017,30,504-520.

-

- 8. Bitenieks, J.; Meri, R.; Zicans, J.; Buks, K. Dynamic Mechanical, Dielectrical, Rheological Analysis of Polyethylene Terephthalate/Carbon Nanotube Nanocomposites Prepared by Melt Processing. Int. J. Polym. Sci.2020,DOI:10.1155/2020/5715463.

-

- 9. Calderas, F.; Sanchea-Solis, A.; Maciel, A.; Manero, O. The Transient Flow of the PET-PEN-Montmorillonite Clay Nanocomposite. Marcromol. Symp.2009, 283,354-360.

-

- 10. Hwang. A.; Bae, J.; Kim, H.; Lim, K. Synthesis of Silica-Polystyrene Core-Shell Nanoparticles via Surface Thiol-Lactam Initiated Radical Polymerization. Eur. Polym. J.2010,46,1654-1659.

-

- 11. Allion, F.; D’Aprea, A.; Dufresne, A.; Kissi, N.; Bossard, F. Poly(oxyethylene) and Ramie Whiskers based Nanocomposites: Influence of Processing: Extrusion and Casting/Evaporation. Cellulose 2011,18,957-973.

-

- 12. Lee, S.; Shim, D.; Lee, J. Rheology of PP/Clay Hybrid Produced by Supercritical CO2 Assisted Extrusion. Macromol. Res.2008, 16,6-14.

-

- 13. Hassanabadi, H.; Wilhelm, M.; Rodrigue, D. Rheological Criterion to Determine the Percolation Threshold in Polymer Nanocomposites. Rheol. Acta.2014,53,869-882.

-

- 14. Tepale, N.; Fernández-Escamilla, V; Álvarez, C.; Flores-Aquino, E.; González-Coronel, V.; Cruz, D.; Sánchez-Cantú, M. Morphological and Rheological Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized using Pluronic P103 as Soft Template. J. Nanomater.2016,DOI:10.1155/2016/7494075

-

- 15. Gaska, K.; Kádár, R.; Rybak, A.; Siwek, A.; Gubanski, S. Gas Barrier, Thermal, Mechanical and Rheological Properties of Highly Aligned Graphene-LDPE Nanocomposites. Polymers 2017, 9, 294.

-

- 16. Azouz, K.; Ramires, E.; Fonteyne, W.; Kissi, N.; Dufresne, A. A Simple Method for the Melt Extrusion of Cellulose Nanocrystal Reinforced Hydrophobic Polymer. ACS Macro Lett 2012, 1, 236-240.

-

- 17. Chung, S.; Hahm, W.; Im, S. Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) Nanocomposites Filled with Fumed Silicas by Melt Compounding. Macromol. Res.2002,10,221-229.

-

- 18. Ghanbari, A.; Heuzey, M. C.; Carreau, P. J.; Ton-That, M. T. A Novel Approach to Control Thermal Degradation of PET/Organoclay Nanocomposites and Improve Clay Exfoliation. Polymer 2012,54,1361-1369.

-

- 19. Shen, Y.; Harkin-Jones, E.; Hornsby, P.; Mcnally, T.; Abu-Zurayk, R. The Effect of Temperature and Strain Rate on the Deformation Behaviour, Structure Development and Properties of Biaxially Stretched PET-Clay Nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Tech. 2011, 70,758-764.

-

- 20. Kim, W.; Kim, C.; Kim, S. Preparation and Characterization of PET Blended with Silica-Polystyrene Hybrid Nanocomposites. Polym. Bull. 2018,75,1505-1517.

-

- 21. Kong, Y.; Hay, J. N. The Measurement of the Crystallinity of Polymers by DSC. Polymer 2002,43,3873-3878.

-

- 22. Ghasemi, H.; Carreau, P. J.; Kamal, M. R.; Uribe-Calderon, J. Preparation and Characterization of PET/Clay Nanocomposites by Melt Compounding. Polym. Eng. Sci.2011,51,1178-1197.

-

- 23. Sun. D.; Kang, S.; Liu, C.; Lu, Q.; Cui. L.; Hu, B. Effect of Zeta Potential and Particle Size on the Stability of SiO2 Nanospheres as Carrier for Ultrasound Imaging Contrast Agents. Int. J. Electrochem.Sci.2016,11,8520-8529.

-

- 24. Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, C. Modification of Spherical SiO2 Particles via Electrolyte for High Zeta Potential and Self-Assembly of SiO2 Photonic Crystal. J. Braz. Chem. Soc.2009,20,46-50.

-

- 25. Moskalyuk, O. A.; Belashov, A. V.; Beltukov, Y. M.; Popova, E. M.; Semenova, I. V.; Yelokhovsky, V. Y.; Yudin, V. E. Polystyrene-Based Nanocomposites with Different Fillers: Fabrication and Mechanical Properties. Polymer 2020,12,2457.

-

- 26. Blackwood, L. Enhancing Mechanical Properties of Polymers through Nanoparticle Reinforcement. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 13, 641.

- 27. Kim, E. S.; Lee, P. C. Fabrication of Strong Self-Reinforced Polyethylene Terephthalate Composites through the In Situ Nanofibrillation Technology. Process 2023, 11,1434.

-

- 28. Dong, M.; Sun, Y.; Dunstan, D. J.; Young, R. J.; Papageorgiou, D. G. Mechanical Reinforcement from Two-Dimensional Nanofillers: Model, Bulk and Hybrid Polymer Nanocomposites. Nanoscale 2024,16,13247.

-

- 29. Saxena, I.; Rana, D.; Gowd, E. B.; Maiti, P. Improvement in Mechanical and Structural Properties of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Nanohybrid. SN Appl. Sci.2019,1,1363.

-

- 30. Yang, F.; Mubarak, C.; Keiegel, R.; Kannan, R. M. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide (scCO2) Dispersion of Poly (ethylene terephthalate)/Clay Nanocomposites: Structural, Mechanical, Thermal, and Barrier Properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016,44779.

-

- 31. Sun, R.; Melton, M.; Safaie, N.; Ferrier, R.; Cheng, S.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, X.; Wang, Y. Molecular View on Mechanical Reinforcement in Polymer Nanocomposites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 117801-117806.

-

- 32. Saeed, K.; Khan, I.; Khan, W. Q.; Khan, M. A.; Khan, H. U.; Khan, T.; Khan, A. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Polyvinyl Alcohol/Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite Films. Polym. Test. 2021, 96, 106860.

-

- 33. Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z. Enhanced Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Polyimide Composites with Aligned Graphene Oxide by Magnetic Field-Assisted Electrospinning. Compos. B Eng. 2019, 166, 246-254.

- 34. Araghi, M.; Bagheri, R. Effect of Rubber Particle Size on Toughening of Epoxy Adhesives. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 134, 1651-1661.

- 35. Choi, H. J.; Kim, M. K.; Kim, B. K.; Lee, S. Y. Preparation and Properties of Poly(ethylene terephthalate)/Organoclay Nanocomposites by In Situ Polymerization. Macromol. Res. 2013, 21, 252-258.

- 36. Altorbaq, A. S.; Krauskopf, A. A.; Wen, X.; Pérez-Camargo, R. A.; Su, Y.; Wang, D.; Müller, A. J.; Kumar, S. K.; kinetics, C. Crystallization Kinetics and Nanoparticle Ordering in Semicrystalline Polymer Nanocomposites. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022,128,101527.

-

- 37. Cheng, F. O.; Mong, T. H.; Jia, R. L. The Nucleating Effect of Montmorillonite on Crystallization of PET/Montmorillonite Nanocomposite. J. Polym. Res.2003, 10,127-132.

-

- 38. Ghijsels, A.; Waals, F. M. T. A. M. Differential Scanning Calorimetry: A Powerful Tool for the Characterization of Thermoplastics. Polym.Test.1980, 1,149-160.

-

- 39. Safonov, A. I.; Starinskii, S. V.; Sulyaeva, V. S.; Timoshenko, N. I.; Gatapova, E. Y. Hydrophobic Properties of a Fluoropolymer Film Covering Gold Nanoparticles. Tech.Phys. Lett. 2017, 43,159-161.

-

- 40. Arrigo, R.; Malucelli, G. Rheological Behavior of Polymer/Carbon Nanotube Composites: An Overview. Mater. 2020, 13, 2771.

-

- 41. Cassagnau, P. Melt Rheology of Organoclay and Fumed Silica Nanocomposites. Polymer 2008, 49, 2183-2196.

-

- 42. Kontou, E. Study of the Matrix–Particle Interactions of Polymer Nanocomposites in the Low-Frequency Regime. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 6804-6815.

-

- 43. Xu, C.; Feng, H.; Li, Y.; Li, L. Design of Surpassing Damping and Modulus Nanocomposites with Tunable Frequency Range via Hierarchical Bio-architecture. Polym. Compos. 2023, 45, 4374-4388.

-

- 44. Sánchez-Solís, A.; Romero-Ibarra, I.; Estrada, M. R.; Calderas, F.; Manero, O. Mechanical and Rheological Studies on Polyethylene Terephthalate-montmorillonite Nanocomposites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2004, 44, 1094-1102.

-

- 45. Baniasadi, H.; Borandeh, S.; Seppala, J. High-performance and Biobased Polyamide/Functionalized Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites Through In Situ Polymerization for Engineering Applications. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306, 21000255.

-

- 46. Hassanabadi, H. M.; Wilhem, M.; Rodrigue, D. A Rheological Criterion to Determine the Percolation Threshold in Polymer Nano-composites. Rheol. Acta. 2014, 53, 869-882.

-

- 47. Li, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L. Rheological Behavior of Polymer Nanocomposites Filled with Spherical Nanoparticles: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Polymer 2021, 231, 124129.

-

- 48. Sheikhi, A.; Afewerki, S.; Oklu, R.; Gaharwar, A. K.; Khademhosseini, A. Effect of Ionic Strength on Shear-Thinning Nanoclay–Polymer Composite Hydrogels. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 2073-2083.

-

- 49. Azeez, A. A.; Rhee, K. Y.; Park, S. J.; Hui, D. Melt Rheological Behavior of High-Density Polyethylene Nanocomposites Filled with Modified Montmorillonite. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 45, 308-314.

- 50. Melo, J. D. D.; Oliveira, M. G. Rheological Properties of Composite Polymers and Hybrid Nanocomposite Polymers. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04187.

- 51. Thareja, P.; Velankar, S. S. Rheology and Morphology of No-Slip Sheared Polymer Blends. J. Rheol. 2005, 49, 209-221.

- 52. Huang, C.-C.; Winkler, R. G.; Sutmann, G.; Gompper, G. Semidilute Polymer Solutions at Equilibrium and under Shear Flow. Macromol 2010, 43, 10107-10116.

-

- 53. Morrow, P. J.; Halley, D. J.; Martin, D. J. Structure–Property Relationships in Biomedical Thermoplastic Polyurethane Nanocomposites. Macromol 2011, 45, 198-210.

-

- 54. Hann, J. M.; Nathalie, L.; Ange, N.; Kuruvilla, J.; Cherian, M.; Sabu, T. Stress Relaxation Behavior of Organically Modified Montmorillonite Filled Natural Rubber/Nitrile Rubber Nanocomposites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 87, 120-128.

-

- 55. Ghasemi, H.; Carreau, P. J.; Kamal, M. R.; Chapleau, N. Effect of Processing Conditions on Properties of PET/Clay Nanocomposite Films. Int. Polym. Process. 2011, 2, 219.

-

- 56. Wellen, R. M. R. Effect of Polystyrene on Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Crystallization. Mater. Res. 2014, 17, 1620-1627.

-

- 57. Choi, B. K.; Park, S. J.; Seo, M. K. Effect of Graphene Oxide on Thermal, Optical, and Gas Permeability of Graphene Oxide/poly (vinyl alcohol) Hybrid Films using Boric Acid. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 17, 7368-7375.

-

- 58. Choudalakis, G.; Gotsis, A. Free Volume and Mass Transport in Polymer Nanocomposites. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 17, 132-140.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 49(6): 769-782

Published online Nov 25, 2025

- 10.7317/pk.2025.49.6.769

- Received on May 8, 2025

- Revised on Jul 20, 2025

- Accepted on Aug 14, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Sanghee Kim

-

Department of Mechanical and Systems Engineering, Hansung University, 116 Samseongyo-ro 16gil, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 02876, Korea

- E-mail: s-kim@hansung.ac.kr

- ORCID:

0000-0001-6208-8931

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.