- Tuning the Length of Polyaniline Nanotubes

Department of Chemistry, Rammohan College, Kolkata 700009, India

- 폴리아닐린 나노튜브의 길이 조절

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) forms a coacervate gel complex with lauric acid (LA) in aqueous medium. It has a typical fibrillar network structure containing a core and a shell. Polyaniline (PANI) was synthesized in the void space of the junction of core and shell. Controlled synthesis and washing gives a variety of polymer morphologies including nanofiber, nanotube and inter-connected network structures of PANI. Again using this typical template and precise synthesis procedures the lengths of the PANI nanotube can be tuned in the micrometer scale. With conductivities in the order of 10⁻2 S/cm, HCl-doped samples demonstrate promising electrical properties, making them suitable for various applications.

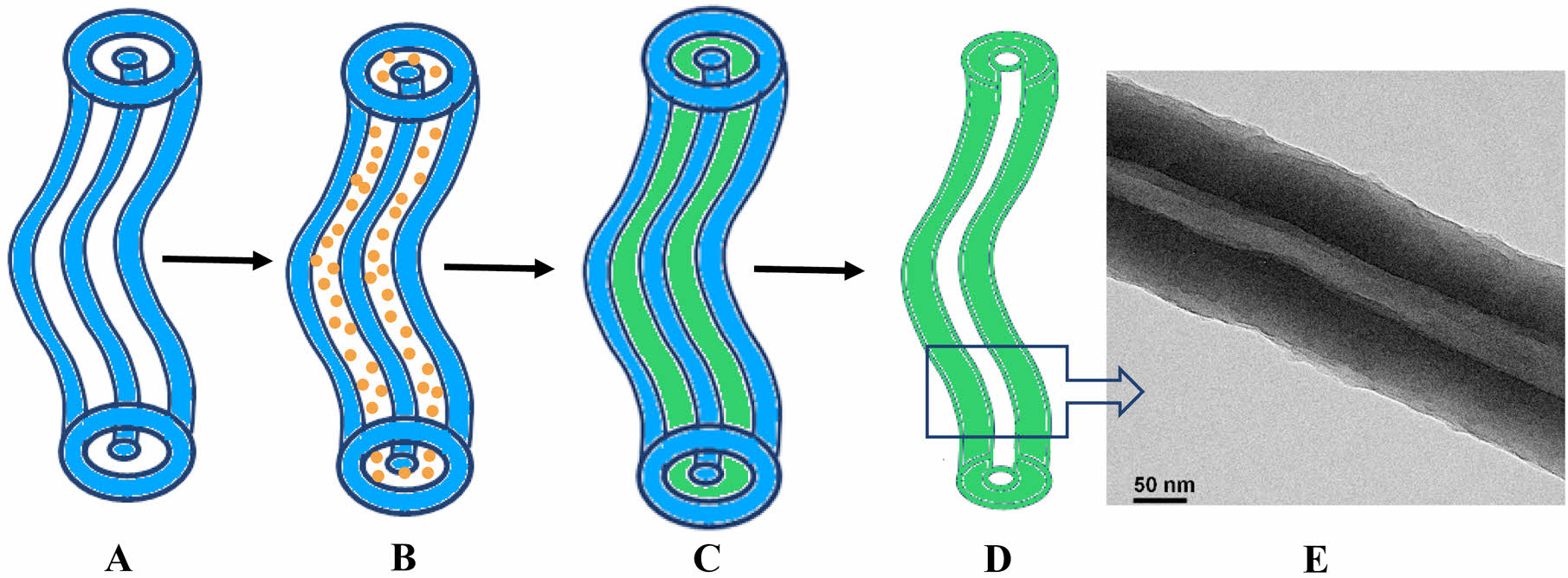

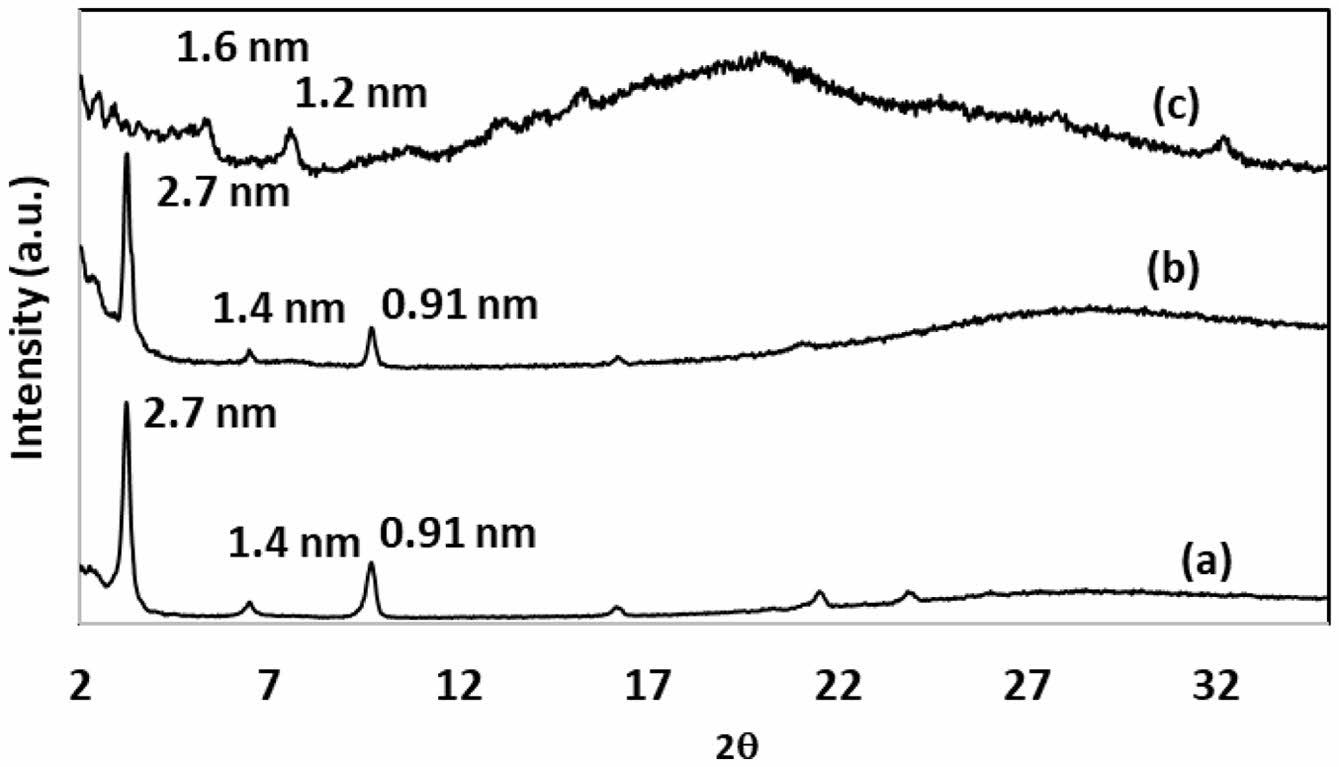

Schematic presentation of (A) CTAB-LA coacervate gel column (B) aniline loaded CTAB-LA coacervate gel column (C) synthesized polyaniline into CTAB-LA coacervate gel template (D) CTAB-LA coacervate gel template removed polyaniline nanotube. (E) TEM image of synthesized polyaniline nanotube.

Keywords: coacervate, gel, sol, polyaniline, nanotube.

I gratefully acknowledge the University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi, for financial support through grant F.PSW-111/15-16 (ERO). I extend my heartfelt appreciation to Prof. A. K. Nandi, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, for his invaluable mentorship and exceptional guidance throughout the course of this work.

The synthesis of nano-dimensional polymers has emerged as a prominent research topic due to their widespread applications and growing recognition among polymer scientists, materials engineers, biochemists, and environmental chemists.1-7 A nano-dimensional polymer is a material composed of polymeric units wherein at least one structural dimension—such as particle size, fiber diameter, or layer thickness—falls within the nanometer scale, typically ranging from 1 to 100 nm.

Polyaniline (PANI) is a highly versatile material. Its ability to transition between different oxidation states and morphologies makes it valuable across various fields. From sensing

applications to protective coatings, its conductivity, environmental stability, and ease of doping offer opportunities for fascinating innovations.8-12

PANI can form nanoparticles, nanotubes, and network structures when prepared using templates, making it suitable for use as an efficient adsorbent,8,9 electrochemical supercapacitors,11 wastewater treatment, oil/water separation,12 nanoreactors,13,14 and other applications.

Additionally, nanostructured polyaniline enhances sensor performance due to its large surface area and low-dimensional conductivity.15-17 PANI undergoes morphological transitions—from nanofiber to nanotube to interconnected network structures—when polymerization occurs in the same complex coacervate gel template across its sol and gel states.10 This ability to switch between nanostructures opens exciting possibilities for tailoring PANI’s properties to specific applications like in sensors, electrochemical devices, or even organic electronics.3,15 In this study, the length of PANI nanotubes was successfully tuned by modifying the template and optimizing the synthesis conditions.

Materials and Methods. Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, Merck, India), lauric acid (LA, Loba Chemie, India), and ammonium persulfate (APS, Merck, India) were used as received without further purification. Aniline (GR grade, Merck, India) was purified by double distillation under a nitrogen atmosphere, and the middle fraction was employed in this study. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, GR grade, Merck, India), ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH), and methanol (International Chemicals, India) were also used as received. Hydrogel templates composed of CTAB and LA were employed in this study to facilitate polyaniline (PANI) polymerization under controlled conditions. A mixture of aniline (5 × 10⁻4 mol), lauric acid (LA, 1.2

× 10⁻3 mol), and an aqueous CTAB solution (5 mL, 3 × 10⁻2 M) was subjected to sonication.

The system was then maintained at 30 ℃ for ten minutes, resulting in gel formation.10 Subsequently, 2 mL 0.25 M ammonium persulfate (APS) solution was added onto the surface of the prepared gel. The setup was left undisturbed at 30 ℃, during which the gel initially transitioned to a brown color. After one hour, the temperature was increased to 45 ℃, leading to a further transformation where the gel turned green in colour.18 The polymerization process was completed within six hours, allowing sufficient time for the reaction to progress and for the intended structural transformation to occur. The resulting polymers were washed sequentially with hot water followed by methanol to remove any residual surfactant. Finally, the samples were dried under vacuum conditions at 60 ℃ to ensure purity and stability prior to characterization experiments.

For molecular weight determination, the synthesized polyaniline salt was initially converted to its emeraldine base (EB) form through alkaline treatment with ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) solution. The viscosity-average molecular weight of PANI-EB was then evaluated via intrinsic viscosity measurements conducted in 97% sulfuric acid (H2SO4) at 27 ℃. The intrinsic viscosity [η] was determined, and molecular weight estimation was performed using the Mark–Houwink equation, applying empirical constants derived from poly(p-phenylene terephthalamide): k = 1.95 × 10-6 and α = 1.36, in H2SO4 medium.2 Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded using KBr pellet technique on a SHIMADZU FTIR instrument (model FTIR-8400S, Japan). Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) analysis of the gel and additional samples was conducted using a Seifert X-ray diffractometer (model C-3000, Germany), operated in reflection mode with a parallel beam optics setup. The measurements employed nickel-filtered Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm) at an operating voltage of 35 kV and a current of 30 mA. Surface morphology was examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, JEOL JSM-6700F, Japan). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis was conducted by depositing a drop of sample solution onto a copper-coated

carbon grid and imaging with a JEOL 2010 EX TEM (Japan) operating at 200 kV. For electrical conductivity measurements, the samples were compressed into pellets (diameter: 1.3 cm) using a hydraulic press. Measurements were performed at room temperature (27 ℃) using a conventional four-probe method with spring-loaded pressure contacts. Electrical contacts were established with silver paste. A constant current (I) supplied by a direct current source electrometer (Keithley, model 617, USA) was passed through the outer probes, while the voltage (V) across the inner probes was recorded using a Keithley digital multimeter (model 2000, USA). Conductivity (σ) was calculated using the relation: σ = (ln2/pd) (I/V), where d represents the thickness of the pellet, determined as the average value obtained from four independent measurements using a screw gauge.

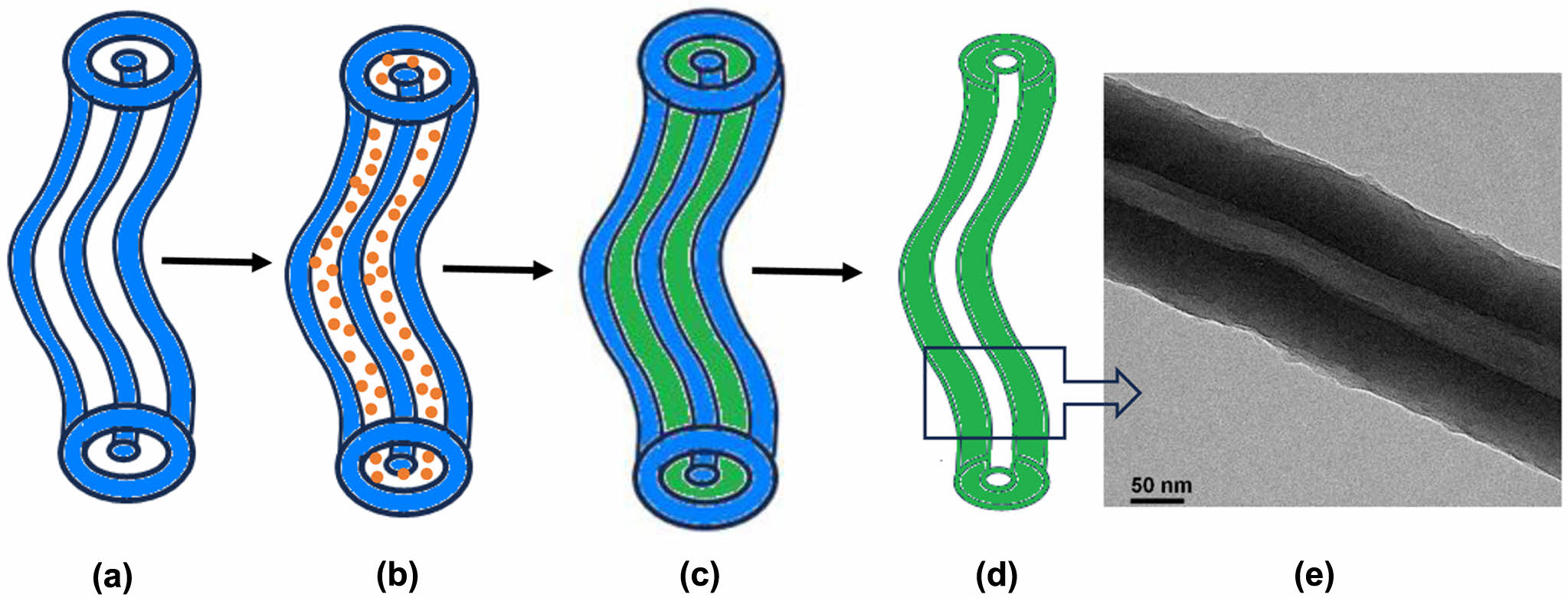

The FTIR spectrum of the synthesized PANI is presented in Figure 1. Two distinct peaks at 1508 and 1590 cm-1 correspond to the benzenoid and quinonoid moieties of PANI, which are essential for understanding its electronic structure and properties. A characteristic peak at 1160 cm-1, attributed to the C–H bending vibration of the quinonoid unit, further confirms the presence of this structural motif within the polymer framework.19-22 The quinonoid structure plays a pivotal role in the electrical conductivity of PANI and its ability to transition between oxidation states. Elemental analysis reveals a composition of 75.5% carbon (C), 9.3% hydrogen (H), and 15.2% nitrogen (N), which closely aligns with the expected stoichiometry of polyaniline synthesized via conventional methods. The observed atomic ratio of C:N (5.8:1) corroborates the anticipated molecular structure of PANI, indicating that the synthesis process likely followed standard oxidative polymerization pathways and preserved a balanced distribution of quinonoid and benzenoid units.23

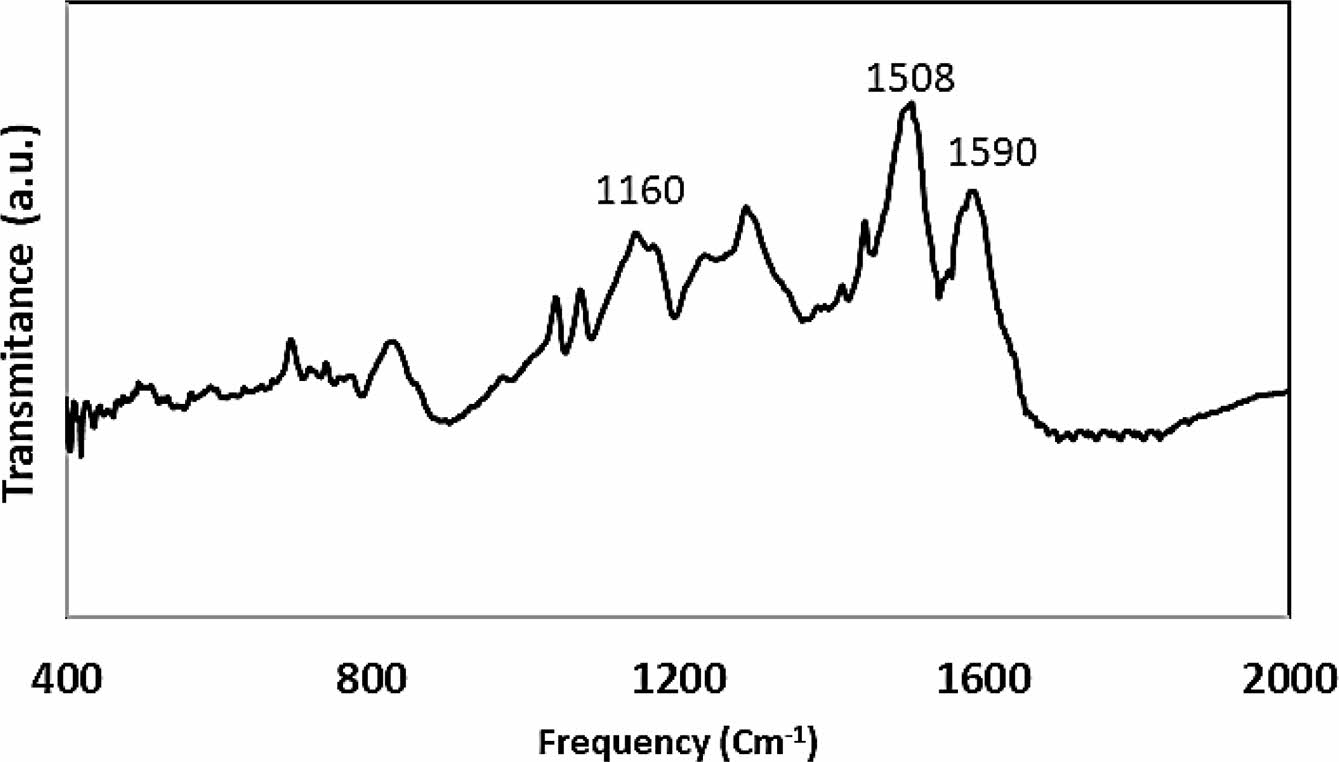

Figure 2 presents the WAXS patterns of the freeze-dried CTAB-LA coacervate gel, the freeze-dried PANI-loaded CTAB-LA coacervate gel, and the synthesized PANI embedded within the matrix. Both the CTAB-LA coacervate gel and the PANI-loaded variant exhibit distinct low-angle diffraction peaks at dhkl values of 0.91, 1.4, and 2.7 nm. These peaks suggest that the incorporation of PANI exerts minimal influence on the interlamellar structure of the CTAB-LA coacervate gel, as evidenced by the retention of peak positions and alterations only in relative peak intensities. Although the precise structure of the complex coacervate remains unknown, but it is widely accepted that ionic interactions between mixed surfactant strands play a key role in stabilizing its formation.24,25

The gelation process in a CTAB–LA mixture is not yet fully understood. However, Nandi et al. proposed a plausible mechanism for the development of various polymer morphologies within this gel system, suggesting that aniline is incorporated into the surfactant strands as an anilinium ion, along with water. A schematic two-dimensional representation of PANI nanotube formation within the CTAB–LA complex coacervate is illustrated in Scheme 1. The presence of excess LA in the mixture promotes the formation of anilinium ions, thereby rendering aniline water-soluble. These ions are confined within the interstitial spaces of the CTAB-LA complex coacervate, where polymerization primarily occurs on the coacervate surface. The synthesized PANI within this template demonstrates peaks at 1.2 and 1.6 nm, which could suggest that PANI forms on the exterior of the interlamellar structure of the CTAB-LA coacervate gel, resulting in a nanotube structure. This is attributed to the ionic nature of the anilinium ion, which prevents its penetration into the micellar interior.

Scheme 1. Schematic presentation of (a) CTAB-LA coacervate gel column; (b) aniline loaded CTAB-LA coacervate gel column; (c) synthesized polyaniline into CTAB-LA coacervate gel template; (d) CTAB-LA coacervate gel template removed polyaniline nanotube; (e) TEM

image of synthesized polyaniline nanotube.

The morphology of PANI is governed by its polymerization kinetics, which are influenced by the diffusion behavior of the initiator within the complex coacervate. In APS-initiated polymerization, the initiator molecules diffuse around the periphery of the coacervate but are unable to penetrate its core due to electrostatic repulsion from lauric acid (LA) anions associated with aniline molecules. This surface-confined distribution of initiators promotes ortho (o) and para (p) position electrophilic attacks on aniline, leading to the formation of phenazine-type units that act as nucleating species.19 Initially adopting a planar sheet-like configuration, these phenazine units gradually bend along the curvature of the coacervate interface, ultimately giving rise to nanotube formation.19-21

Upon completion of polymerization, the surfactant strands are removed via leaching with water and methanol, thereby revealing the nanotube morphology. Polymerization at low temperatures yields long PANI nanotubes, whereas high-temperature conditions result in shorter nanotubes. This trend indicates that the nanotube length can be effectively tuned through controlled adjustments to the synthesis parameters. To obtain intermediate-length PANI nanotubes, the synthesis protocol can be modified by initiating chain growth at a low temperature, followed by a propagation phase during which the template temperature is gradually increased. This temperature modulation alters the length and width of the coacervate column and is sustained until polymerization is complete, thus enabling the design of nanotubes with tailored intermediate dimensions.19,20

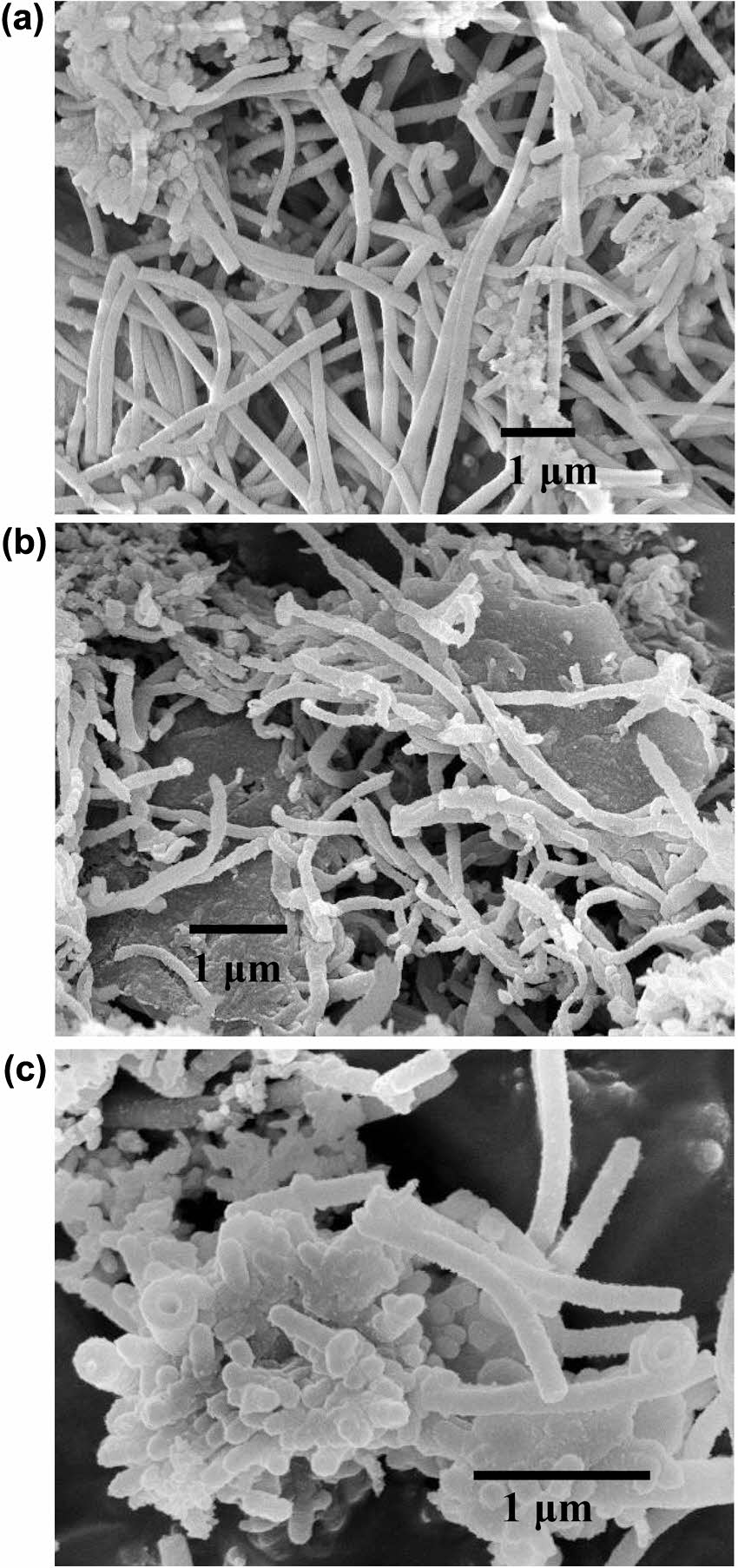

Figure 3 compares the SEM morphologies of PANI nanotubes synthesized under different polymerization conditions. Micrograph A depicts nanotubes exceeding 5 μm in length, formed within a gel template at 30 ℃ using APS solution. Micrograph B illustrates nanotubes approximately 2.4 μm in length, prepared via sequential polymerization-initially within a gel template at 30 ℃, followed by a sol template at 45℃. Micrograph C presents shorter nanotubes, roughly 1 μm in length, generated within a sol template at 42 ℃ using the same initiator. Increasing the temperature of the CTAB-LA coacervate gel causes the coacervate columns to become more labile, leading to shorter lengths and narrower diameters. It was observed that the longest PANI nanotubes formed within the gel state, the shortest in the sol state, and intermediate lengths were achieved under mixed state conditions. These findings suggest that nanotube length is primarily governed by the structural characteristics of the coacervate column and the diffusion dynamics of the APS solution into the interstitial regions of the LA micelles.

The viscosity-average molecular weights of three polyaniline (PANI) nanotube samples-of approximate lengths ~1 μm, ~2.4 μm, and >5 μm-were determined based on intrinsic viscosity ([η]) measurements. The corresponding [η] values were found to be 0.62, 0.72, and 0.83 dL/g, respectively. Using the established Mark–Houwink relationship, the calculated molecular weight values for the ~1 μm, ~2.4 μm, and >5 μm nanotubes were approximately 10800, 12600, and 14700, respectively (rounded to the nearest hundred). The observed variation in viscosity-average molecular weight among the PANI nanotube samples may be attributed to differences in polymerization temperature. Elevated polymerization temperatures can accelerate chain growth kinetics, alter nucleation rates, and influence oxidative coupling pathways, thereby affecting the length and entanglement of polymer chains.

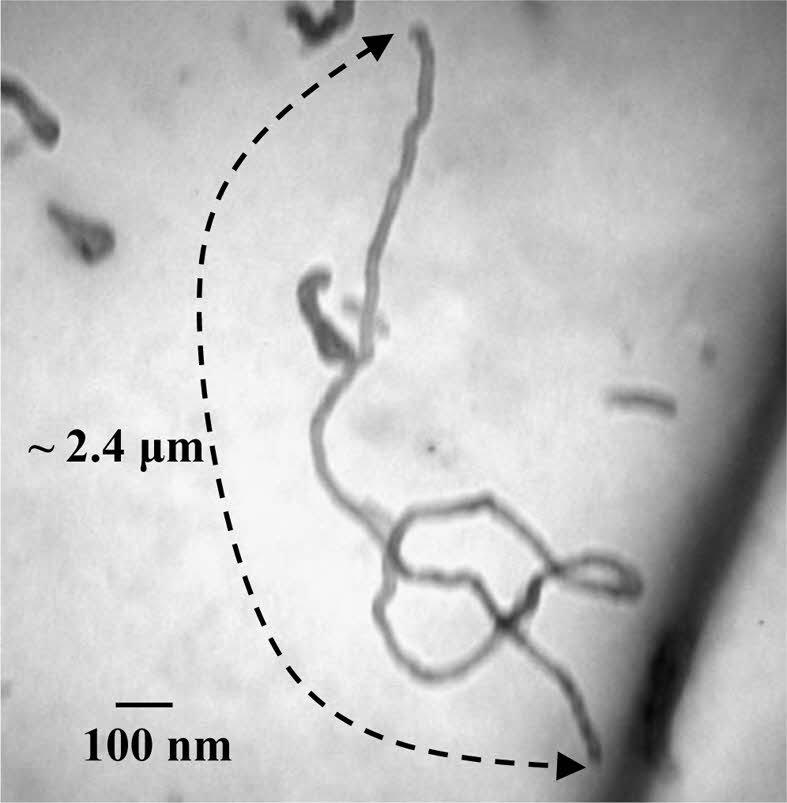

Figure 4 presents TEM micrographs of PANI nanotubes approximately 2.4 μm in length, synthesized via sequential templating-initially in a gel matrix at 30 ℃, followed by a sol matrix at 45 ℃ using APS as the oxidizing agent. Notably, an individual PANI nanotube measuring ~2.4 μm is distinctly observed in the TEM images. For dc conductivity analysis, the sample was converted to its emeraldine salt (ES) form via HCl doping and evaluated using the four-probe method. The resulting conductivity of 1.14 × 10⁻2 S/cm demonstrates a sufficiently high level for potential integration into various functional applications.

|

Figure 1 FTIR spectra of PANI nanotube. |

|

Figure 2 WAXS pattern of (a) Freeze-dried CTAB-LA coacervate gel; (b) freeze-dried PANI loaded CTAB-LA coacervate gel; (c) synthesized PANI into this matrice. |

|

Figure 3 SEM micrograph of polyaniline nanotube: (a) > 5 μm length; (b) ~ 2.4 μm length; (c) ~ 1 μm length. |

|

Figure 4 TEM image of synthesized polyaniline nanotube of length ~ 2.4 μm. |

Controlled variation of thermal conditions has been demonstrated as an effective strategy for tailoring PANI nanotube length, without necessitating alterations to either the template or the initiator system. This approach to synthesizing polyaniline (PANI) nanotubes is both innovative and methodologically significant, offering promising potential for enhanced performance and structural control. The utilization of a complex coacervate gel template presents a straightforward yet effective strategy for achieving controlled morphological outcomes in PANI nanostructures. Owing to its reproducibility and cost-efficiency, this technique holds significant promise for scalable implementation across diverse functional domains, including nanoreactors, actuators, gas-separation membranes, and neural interface devices. The dual-surface exposure of these nanotubes may significantly enhance their efficiency in sensor technologies and catalytic processes by increasing active surface area and accessibility. Notably, similar template-assisted synthesis approaches have also been investigated for other polymers, thereby broadening the scope of nano-dimensional material design and expanding the toolkit for functional nanostructure engineering.

- 1. Altintas, O.; Fischer, T. S.; Barner-Kowollik, C. Synthetic Methods Toward Single-Chain Polymer Nanoparticles; Pomposo, J. A.; Eds.; Single‐Chain Polymer Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Simulations, and Applications. Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim 2017; pp. 1-45.

-

- 2. Andreatta, A.; Cao, Y.; Chiang, J. C.; Heeger, A. J.; Smith, P. Electrically-conductive Fibers of Polyaniline Spun From Solutions in Concentrated Sulfuric Acid Synth. Met. 1988, 26, 383-389.

-

- 3. Nitti, A.; Carfora, R.; Assanelli, G.; Notari, M.; Pasini, D. Single-Chain Polymer Nanoparticles for Addressing Morphologies and Functions at the Nanoscale: A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022,5, 13985-13997.

-

- 4. Alqarni, M. A. M.; Waldron, C.; Yilmaz, G.; Remzi Becer, C. Synthetic Routes to Single Chain Polymer Nanoparticles (SCNPs): Current Status and Perspectives. Macro. Rapid Commn. 2021, 42, 2100035.

-

- 5. Aiertza, M. K.; Odriozola, I.; Cabañero, G.; Grande, H-J.; Loinaz, I. Single-chain Polymer Nanoparticles. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2012, 69, 337-46.

-

- 6. Kröger, A. P. P.; Paulusse, J. M. J. Single-chain Polymer Nanoparticles in Controlled Drug Delivery and Targeted Imaging. J. Control. Release. 2018, 86, 326-347.

-

- 7. Hamelmann, N. M.; Paulusse, J. M. J. Single-chain Polymer Nanoparticles in Biomedical Applications. J. Control. Release. 2023, 356, 26-42.

-

- 8. Saad, M.; Tahir, H.; Khan, J.; Hameed, U.; Saud, A. Synthesis of Polyaniline Nanoparticles and Their Application for the Removal of Crystal Violet Dye by Ultrasonicated Adsorption Process Based on Response Surface Methodology. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017,34, 600-608.

-

- 9. Ayad, M.; El-Hefnawy, G.; Zaghlol, S. Facile Synthesis of Polyaniline Nanoparticles, Its Adsorption Behavior. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 217, 460-465.

-

- 10. Garai, A.; Nandi, A. K. Tuning of Different Polyaniline Nanostructures From a Coacervate Gel/sol Template. Synth. Met. 2009, 159, 757-760.

-

- 11. Sk, M. M.; Yue, C. Y. Synthesis of Polyaniline Nanotubes Using the Self-assembly Behavior of Vitamin C: a Mechanistic Study and Application in Electrochemical Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014, 2, 2830-2838.

-

- 12. Mondal, S.; Rana, U.; Das, P.; Malik, S. Network of Polyaniline Nanotubes for Wastewater Treatment and Oil/Water Separation. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 1, 1624-1633.

-

- 13. Swisher, J. H.; Jibril, L.; Petrosko, S. H.; Mirkin, C. A. Nanoreactors for Particle Synthesis. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 428-448.

-

- 14. Petrosko, S. H.; Johnson, R.; White, H.; Mirkin, C. A. Nanoreactors: Small Spaces, Big Implications in Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7443-7445.

-

- 15. Wojkiewicz, J. L.; Bliznyuk, V. N.; Carquigny, S.; Elkamchi, N.; Redon, N.; Lasri, T.; Pud, A. A.; Reynaud, S. Nanostructured Polyaniline-based Composites for Ppb Range Ammonia Sensing. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2011, 160, 1394-1403.

-

- 16. Mishra, P. K.; Sharma, H. K.; Gupta, R.; Manglik, M.; Brajpuriya, R. A Critical Review on Recent Progress on Nanostructured Polyaniline (PANI) Based Sensors for Various Toxic Gases: Challenges, Applications, and Future Prospects. Microchem. J. 2025, 208, 112369.

-

- 17. Askar, P.; Kanzhigitova, D.; Tapkharov, A.; Umbetova, K.; Duisenbekov, S.; Adilov, S.; Nuraje, N. Hydrogen Sensors Based on Polyaniline and Its Hybrid Materials: a Mini Review. Discover Nano 2025, 20, 68.

-

- 18. Gizdavic-Nikolaidis, M.; Travas-Sejdic. J.; Kilmartin, P. A.; Bowmaker, G. A.; Cooney, R. P. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity of Aniline and Polyaniline. Current Appl. Phys. 2004, 4, 343.

-

- 19. Stejskal, J.; Sapurina, I.; Trchova, M.; Konyushenko, E. N.; Holler, P. The Genesis of Polyaniline Nanotubes. Polymer 2006, 47, 8253.

-

- 20. Venancio, E. C.; Wang, P.-C.; MacDiarmid, A. G. The Azanes: A Class of Material Incorporating Nano/micro Self-assembled Hollow Spheres Obtained by Aqueous Oxidative Polymerization of Aniline. Synth. Metals. 2006, 156, 357.

-

- 21. Trchova, M.; Sedenkova, I.; Konyushenko, E. N.; Stejskal, J.; Holler, P.; Ciric-Marjanovic, G.; Evolution of Polyaniline Nanotubes: The Oxidation of Aniline in Water. J.Phys.Chem. B. 2006, 110, 9461.

-

- 22. Li, Y.; Zheng, J.-L.; Feng, J.; Jing, X.-L. Polyaniline Micro-/nanostructures: Morphology Control and Formation Mechanism Exploration. Chem. Pap. 2013, 67, 876-890.

-

- 23. Zeng, X.-R.; Ko, T.-M. Structures and Properties of Chemically Reduced Polyanilines. Polymer 1998, 39, 1187-1195.

-

- 24. Burgess, D. J. Practical Analysis of Complex Coacervate Systems. J. Colloid InterfaceSci. 1990, 140, 227-238.

-

- 25. Nallamilli, T.; Ketomaeki, M.; Prozeller, D.; Mars, J.; Morsbach, S.; Mezger, M.; Vilgis, T. Complex Coacervation of Food Grade Antimicrobial Lauric Arginate with Lambda Carrageenan. CRFS 2021, 4, 53-62.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 49(6): 793-798

Published online Nov 25, 2025

- 10.7317/pk.2025.49.6.793

- Received on May 22, 2025

- Revised on Jul 19, 2025

- Accepted on Jul 20, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Ashesh Garai

-

Department of Chemistry, Rammohan College, Kolkata 700009, India

- E-mail: agchemistry@rammohancollege.ac.in

- ORCID:

0000-0003-0697-5493

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.