- Effect of Twin-screw Modification Time on Waste Rubber Powder Reinforced Natural Rubber

Juyuan Dong, Hao Duan, Keyu Peng, Su Zhang, Guangshan Yao, Zheng Huang, Yuan Jing*,†

, and Guangyi Lin†

, and Guangyi Lin†

College of Electromechanical Engineering, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, 266061, P. R. China

*Qingdao University of Science and Dongying, 257029, P. R. China- 이축 스크류 개질 시간이 폐고무 분말 강화 천연고무의 물성에 미치는 영향

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

Waste tires cause serious black pollution, and green, efficient recycling of waste tires is one of the key ways to solve this problem.This article proposes a twin-screw modification method and explores the influence of different twin-screw extrusion times on the modification effect of waste rubber powder (WRP). The modified WRP is flocculated with natural rubber latex to obtain the master rubber. The experimental results showed that after two rounds of twin-screw surface modification, the mechanical properties of WRP/natural rubber latex (NRL) composite materials were significantly improved compared to those without twin-screw surface modification. The tensile strength, tear strength, and elongation at break were increased by 19.44%, 27.36%, and 37.55%, respectively. In addition, the tensile strength retention rate and tear strength retention rate of the modified composite after aging are 78.26% and 76.43% respectively compared with those before aging, showing good anti-aging performance, which is of great significance for improving the service life and reliability of the composite.

This study innovatively proposes a twin-screw modification method for waste rubber powder and explores the influence of modification times on the modification effect of waste rubber powder. The experimental results showed that compared with unmodified waste rubber powder (WRP)/natural rubber latex (NRL) composites, the mechanical properties of WRP/NRL composites were significantly improved after two rounds of twin-screw surface modification. The tensile strength, tear strength, and elongation at break were increased by 19.44%, 27.36%, and 37.55%, respectively. This indicates that the twin-screw modification process can effectively improve the compatibility between waste rubber powder and natural rubber, and enhance the overall performance of composite materials. In addition, the tensile strength retention and fracture elongation retention of the rubber composite material reach their maximum values, reaching 76.43% and 78.26%, showing better anti-aging performance, which is of great significance for improving the service life and reliability of the composite materials.

Keywords: waste rubber powder, natural rubber, recycled rubber, twin-screw, desulfurization regeneration.

This work was supported by the Key Research and Developm ent Plan of Qingdao Natural Science Foundation (24-4-4-zrjj-192-jch).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Rubber is a key polymer material in modern society. With its unique viscoelasticity and low elastic modulus, it is widely used in many fields such as automotive tires, industrial seals, medical equipment, and building shock absorbers, promoting the development of the national economy. With the growth of the global economy and the advancement of rubber product technology, the demand for tires has increased significantly, and the problem of waste tire disposal has become prominent.1 Resource utilization has become a hot topic of global concern. As of 2023, the annual production of waste tires worldwide is approximately 1.5 billion pieces,2 mainly consisting of natural rubber, synthetic rubber, carbon black, and metals.3 Waste tires have high durability and are difficult to naturally degrade. Improper disposal can cause environmental problems such as soil, air pollution, and ecological damage. The resource utilization of waste tires has significant economic and environmental significance. On the one hand, replacing natural rubber can reduce overexploitation and alleviate resource shortages; On the other hand, compared to incineration or landfill, it can reduce carbon emissions and achieve green development.4 The preparation of waste rubber powder is the core process of resource utilization, and mechanical crushing technology is the main method, including room temperature crushing and low-temperature crushing.5 Room temperature crushing has low energy consumption but uneven powder distribution. Low temperature crushing has controllable particle size and excellent performance, but requires liquid nitrogen freezing treatment.6 Ultrasonic treatment utilizes cavitation effect to break down rubber molecular chains, producing highly dispersed and active waste rubber powder (WRP). WRP has broad application prospects in the production of rubber products. It can be added as a filler or modifier to the rubber matrix for the preparation of tires, conveyor belts, seals, etc. It can enhance rubber performance, reduce production costs, and achieve green production.7 Traditional production of WRP primarily relies on ambient-temperature mechanical grinding. This method suffers from significant drawbacks: high energy consumption, excessive noise, and severe dust pollution during production. The resulting rubber powder exhibits coarse particle surfaces, uneven particle size distribution, and degradation of rubber molecular chains due to high temperatures, leading to diminished performance and limiting its suitability for subsequent high-value applications. Wet rubber mixing technology, as an environmentally friendly and efficient rubber mixing method, has significant advantages compared to traditional dry rubber mixing. By dispersing rubber and fillers in water, dust pollution is avoided, while improving the dispersibility of fillers and the overall performance of rubber materials.8,9 Adopting hydrophilic treatment and high-speed shear technology to improve the compatibility between WRP and latex can decompose latex flocs, enhance the interfacial bonding between rubber WRP and rubber matrix, improve the dispersibility of rubber WRP in the matrix, thereby maximizing the reinforcing effect of WRP on the rubber matrix and improving the mixing quality of wet rubber. Twin-screw extruder technology is known for its excellent mixing ability and gentle material handling, which can achieve efficient mixing at lower temperatures, reduce energy consumption, and maintain the original properties of materials.10 By modifying WRP through a twin-screw extruder, the physical and chemical properties of the WRP can be significantly improved, enhancing its compatibility with the rubber matrix, and thereby improving the mechanical properties and durability of the final product.11

Lakhiar, MT et al.12 studied the thermodynamic properties of waste tire WRP. They explored the addition of waste tire rubber powder to concrete to improve its sound absorption and thermal insulation properties, but also pointed out that this would significantly reduce the mechanical properties of cement-based composite materials. The article also mentioned the surface modification methods of using WRP to modify concrete, including the use of coupling agent KH560, sodium hydroxide, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), methyl hydroxyethyl cellulose ether (MHEC), and a mixed modification method using tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) as a precursor. Hao Kuanfa et al.13 discussed the wet mixing of waste tire rubber powder (WPRP) and natural rubber latex (NRL), which realized the high value and economic recovery of waste rubber. Flocculation of natural rubber (NR) lotion is realized by mechanical mixing and shearing, and WPRP and carbon black (CB) are added, without acid reagent. The paper also mentioned the influence of wood plastic composites on the properties of rubber composites, and how the irregular hydroxyl containing surface of wood plastic composites obtained by high-pressure water jet accelerated the flocculation of NRL. Candau et al.14 investigated the effect of mechanical recycling types of waste rubber particles on the tensile properties of waste rubber/natural rubber blends. The waste of ground tire rubber (GTR) was found to exhibit enhanced stiffness and strength in both low-temperature grinding and high shear mixing processes, resulting in composite materials at all strain rates and test temperatures. This is attributed to the reinforcing effect of waste and its ability to nucleate strain-induced crystallization (SIC) in the NR matrix. Kaliyappan et al.15 investigated the effects of different ratios of GTR on blends of NR ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM) or NR/chloroprene rubber (CR) composites, and found that adding 10 phr of GTR was suitable for NR in EPDM or CR composites. Adding too many copies can lead to performance degradation. Innes, J.R. et al.16 converted the produced desulfurization powder into recyclable thermoplastic vulcanizate (TPV) through twin-screw extrusion, demonstrating great potential in transitioning to sustainable products and achieving high-value utilization of WRP.

Although some achievements have been made in the application research of WRP, there are still many problems in practical applications. Due to uneven distribution of WRP and poor interface bonding with the matrix, the performance of composite materials fluctuates greatly and their stability is poor, which limits their application range in high-performance rubber products.

Against this backdrop, this study innovatively combines twin-screw desulfurization technology with wet rubber processing techniques to achieve efficient regeneration of WRP. By employing twin-screw modification of WRP, desulfurization and regeneration treatments are applied at different time intervals. The feasibility of partially substituting natural rubber with this material in formulation systems is systematically explored, thereby reducing natural rubber consumption. During the reuse process, an environmentally friendly wet method is introduced to minimize environmental impact. This further optimizes the process flow and drives technological innovation, aiming to enhance the added value of WRP and maximize economic benefits. Utilizing advanced equipment such as twin-screw extruders, physical or chemical methods are employed to modify WRP, significantly improving its dispersibility and compatibility with rubber. Compared to conventional methods, this strategy not only substantially reduces sulfur content and enhances material uniformity but also leverages the wet process to strengthen the interfacial compatibility between WRP and natural latex. This results in improved tensile properties and elastic modulus of the composite material. This integrated approach not only enhances recycling efficiency, optimizes material interface behavior, and improves industrial feasibility, but also provides a novel technical pathway for the large-scale application of WRP in high-value rubber products. It demonstrates strong scientific innovation and engineering application value.

Materials. NRL: Qingjinreina Rubber Technology Co., Ltd. SiO2: Shandong Lianke Technology Co., Ltd. Zinc oxide (indirect method) (ZnO): Weifang Longda Zinc Industry Co., Ltd. Stearic acid (SA): Shandong Shangshun Chemical Co., Ltd. Antioxidant 4020: Shengao Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. Accelerator (CZ): Rongcheng Chemical Plant Co., Ltd. 3-Glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane (KH-560): Zhongjie New Materials Co., Ltd. WRP: Daqing Haoyue Rubber Manufacturing Co., Ltd. Oil V600: Shandong Taichang Petrochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Deionized water: homemade.

Instruments and Equipment. XK-160 type open mill: Dalian Huahan Rubber Machinery Co., Ltd; Internal mixer RM-200C, Harbin Haber Electric Technology Co., Ltd; XB220A electronic analytical balance: Precisa company; M-3000AU sealed rotorless rheometer, MV-3000AU new Mooney viscosity testing machine, AI-7000-MU1 new electronic universal material testing machine, GT-7012-DA rubber abrasion machine, GT-7016-AR3 pneumatic automatic cutting test piece machine, GS-709N Shore A hardness tester: Taiwan High Speed Rail Testing Instrument Co., Ltd; SHR series high-speed mixer: Dongguan Yibang Machinery Co., Ltd; Waste rubber recovery machine: self-made; SN-DZF-6050 Thermal Oxygen Aging Chamber: Shanghai Shangpu Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd; SU8010 Scanning Electron Microscope: HITACHI Corporation, Japan; QLB-400X2 flat vulcanizing machine: Qingdao Yadong Rubber Machinery Factory; TSE-65B twin-screw extruder: Nanjing Hisilicon Extrusion Equipment Co., Ltd.

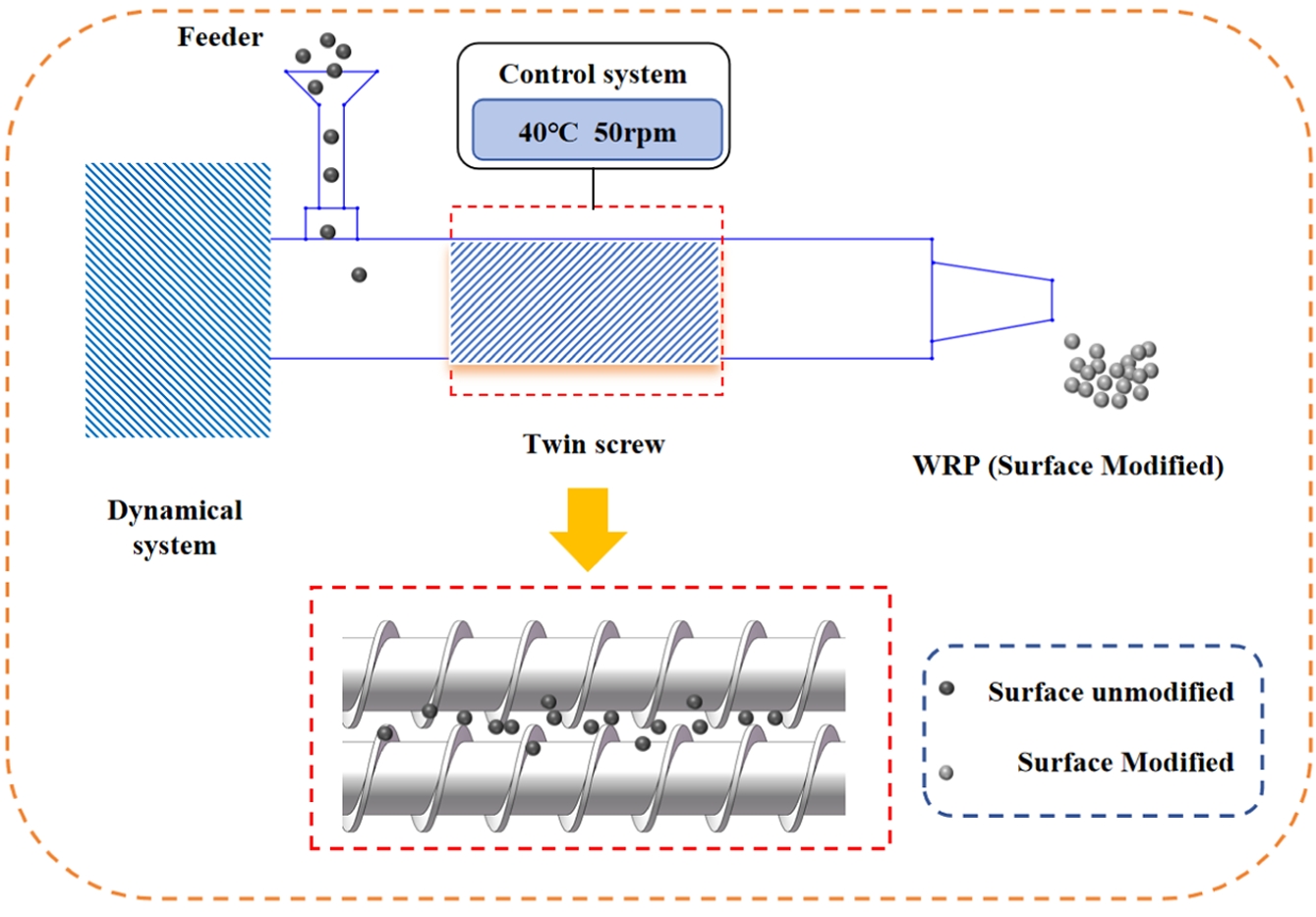

Preparation of Modified WRP. In this study, the parameter selection for the twin-screw desulfurization and regeneration process was determined through a series of systematic optimization experiments. We focused on investigating the effects of two key parameters: temperature (140-180 ℃) and screw speed (40-80 rpm). Experimental results indicate: At excessively low temperatures (140 ℃), desulfurization efficiency is insufficient, resulting in limited sulfur reduction and poor reclaimed rubber properties.At excessively high temperatures (180 ℃), material scorching occurs, causing polymer chain degradation and significant performance deterioration; At excessively low speeds (40 rpm), mixing is inadequate, leading to poor reaction uniformity; At excessively high speeds (80 rpm), increased shear-induced heating caused localized overheating, adversely affecting material structure. Through comprehensive comparison of performance metrics-including sulfur content, tensile strength, and elastic modulus-under various process conditions, we ultimately determined that desulfurization efficiency and overall performance of WRP were optimized at 160 ℃ and 60 rpm. Consequently, this parameter set was selected as the experimental condition in the original text.

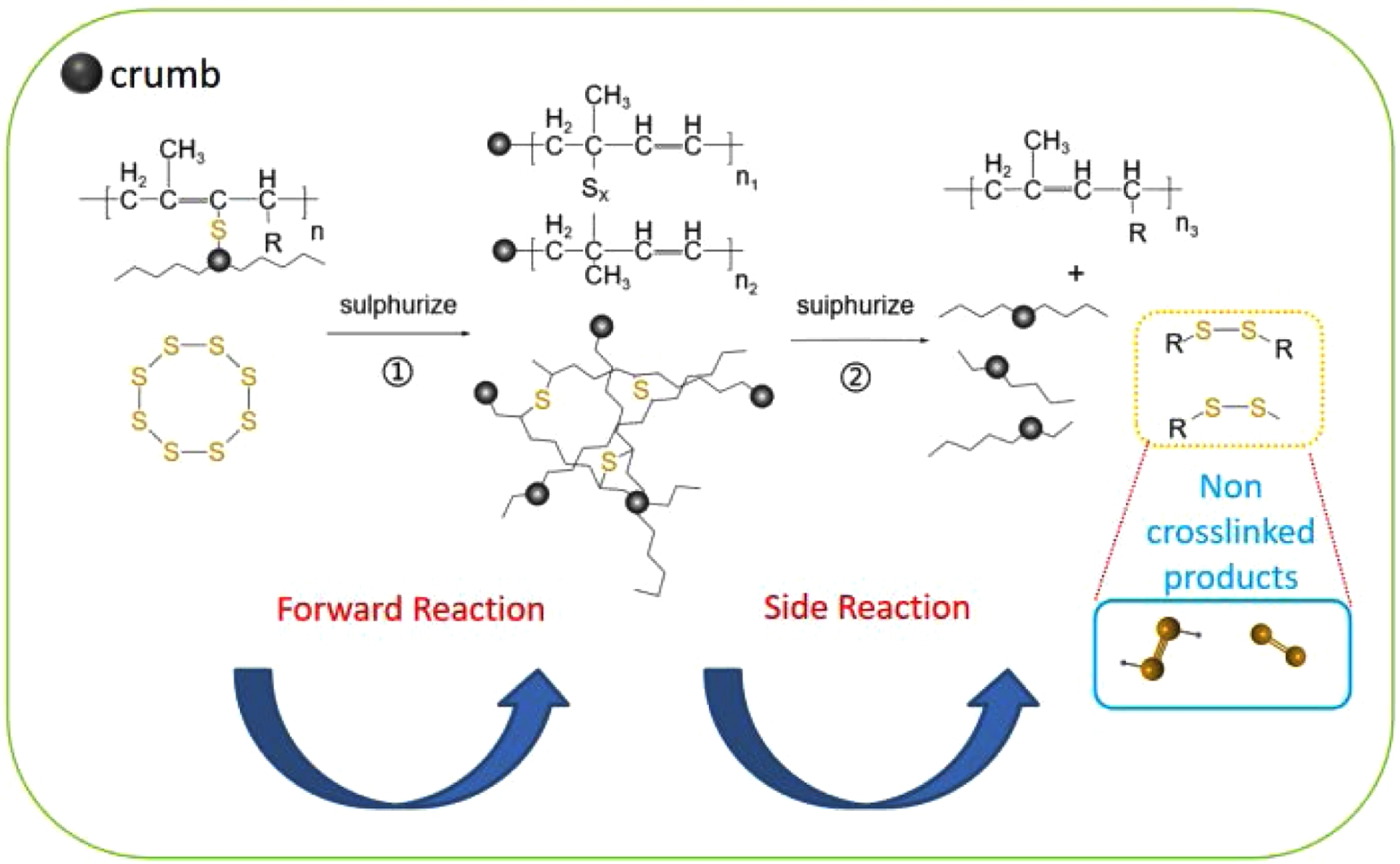

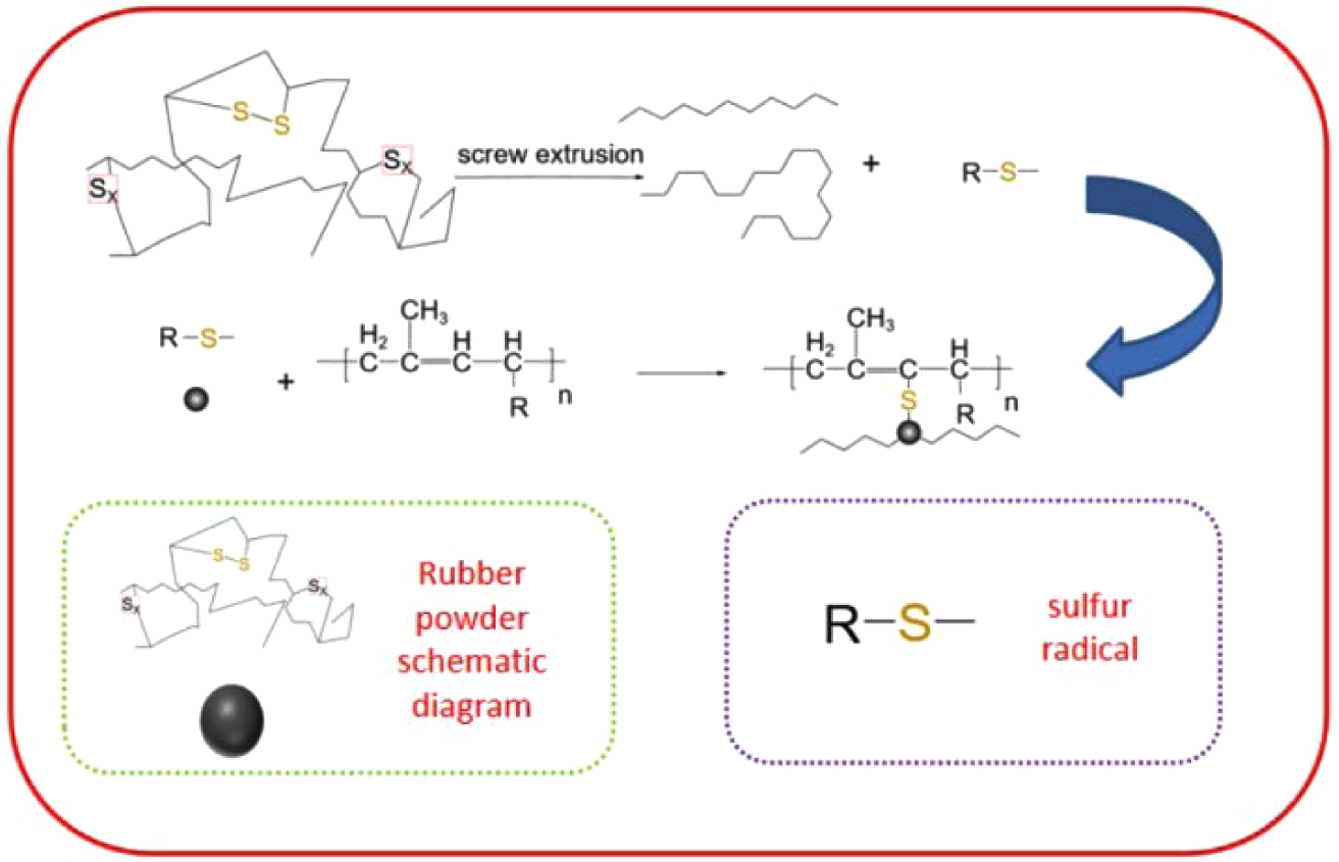

Based on the process diagram of WRP modification shown in Figure 1. Set the temperature of the twin-screw extruder to 160 ℃ and the main screw speed to 60 rpm. When the equipment reaches the set working conditions, add the WRP to the feeding port and pass it through the twin-screw extruder 0 times, 1 time, 2 times, 3 times, and 4 times, denoted as WRP-0, WRP-1, WRP-2, WRP-3, and WRP-4, respectively.

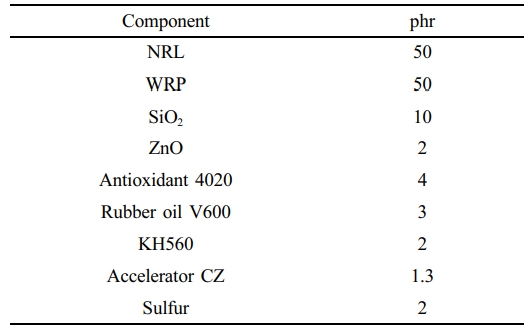

Preparation of NRL/WRP Composites. The basic formula is shown in Table 1. The preparation steps of vulcanized rubber are as shown in Figure 2. First, pour the natural rubber latex into the mixing tank filled with flocculant for flocculation. Place the flocculated mother gel in an oven and dry it to a constant weight. Add the weighed NRL, WRP, zinc oxide, stearic acid, anti-aging agent 4020, and rubber oil into the internal mixer (RM-200C, Harbin Haber Electric Technology Co., Ltd.), set the temperature to 90 ℃, and the rotor speed to 80 r/min. All materials are mixed in the internal mixer for 5 minutes, with a controlled temperature of around 110 ℃. After the internal mixing is completed, they are compressed in the open mill and stored at room temperature for 8 hours; Then add it to the open mill, add S and CZ, and press out 10-15 times.At this point, the roller spacing of the drum gradually decreases to make the mixture uniform.Then, the rubber was kept at room temperature for 8 hours and its rheological properties were tested on a rotorless vulcanizing machine. Finally, vulcanization is carried out in a flat vulcanizing machine with a set temperature of 150 ℃, pressure of 10 MPa, and vulcanization time of 1.3 × tc90.

In this study, rubber vulcanized rubber samples were numbered based on whether they underwent twin-screw modification to ensure the traceability and systematicity of the experiment. The specific numbering rule is as follows: NRL/WRP-0 refers to the rubber material made from unmodified rubber powder without twin-screw modification; NRL/WRP-1 refers to the rubber material obtained by modifying the rubber powder with twin-screw once; NRL/WRP-2 refers to the rubber material obtained by modifying the rubber powder twice with twin-screw; NRL/WRP3 refers to the rubber material obtained by modifying rubber powder with twin-screw for 3 times; NRL/WRP-4 refers to the rubber material obtained by modifying rubber powder with twin-screw for 4 times.

Analyses and Tests. Mooney viscosity: According to the requirements of GB/T1223.1-2000 for the sample, use a large rotor, preheat to 100 ℃, and place the sample on a Mooney viscosity meter at a temperature of 100 ± 0.5 ℃ for 5 minutes. Sulfurization characteristics: According to the requirements of GB/T16584-1996 for the sample, after the temperature of the upper and lower mold cavities of the rotorless rheometer reaches 150 ℃ and stabilizes, the sample is placed and tested for 60 minutes. Tensile stress-strain:According to the requirements of GB/T528-2009 for the specimen, cut 3 dumbbells shaped and 3 right-angled splines from the specimen, select 3 positions of the specimen to test the thickness, take the average value, and input it into the testing machine for testing at a tensile rate of 500 mm/min. Shore A hardness: tested according to GB/T531-2009. DIN abrasion: tested on a DIN abrasion tester according to GB/T986-1988.Compression permanent deformation: According to the requirements of GB/T1683-2018 for compression permanent deformation specimens, cylindrical specimens are prepared by compression molding vulcanization method for testing. The testing conditions are: placed at 100 ± 1 ℃ for 48 hours. Aging test: According to GB/T3512-2014, the vulcanized rubber is cut into pieces and placed in a hot oxygen aging chamber at 100 ± 1 ℃ for 48 hours of aging.Scanning electron microscope (SEM): After gold spraying treatment, the morphology of the dumbbell-shaped tensile fracture section of NR composite material was observed using SEM.

|

Figure 1 Process diagram of modified waste rubber powder preparation. |

|

Figure 2 Preparation process of vulcanized rubber. |

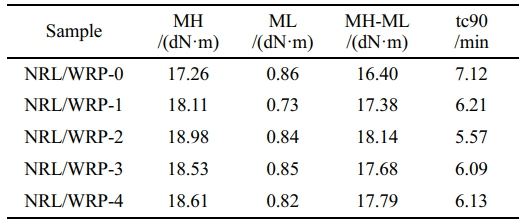

Rheological Properties of NRL/WRP Composites. The vulcanization characteristics data of NRL/recycled rubber compounds prepared with different fillers are shown in Table 2. MH is the highest torque. ML is the minimum torque. MH-ML is the torque difference. MH-ML can be used to indicate the degree of crosslinking of compounds.

From Table 2, it can be seen that the effect of 150 ℃ on the vulcanization characteristics of NRL/WRP composite materials was studied. This includes MH, ML, and tc90. The results showed that the MH-ML of NRL/WRP composite materials treated by twin-screw extrusion was higher than that without twin-screw extrusion treatment, and the degree of crosslinking was higher.17

After passing through the twin-screw, the torque difference of the composite material first increases and then decreases. The increase is due to the high temperature during the extrusion process under the action of the twin-screw, which causes thermal degradation of the rubber molecular chains in the WRP and triggers new cross-linking reactions. Thermal action can provide sufficient energy to cause the active groups in the rubber molecular chain to react, forming new cross-linking bonds and increasing the degree of rubber material; The decrease is due to the mechanical shear and thermal effects of the extruder breaking some cross-linking bonds, resulting in a decrease in the density of the cross-linking network. The desulfurization regeneration process leads to partial dissociation of the cross-linked structure of vulcanized rubber, increasing the degree of freedom of molecular chains, resulting in more S-S bond breakage, as well as partial C-C bond breakage.18 Therefore, the crosslinking density of the compound slightly decreases; But after multiple extrusions, the cross-linking structure of the WRP was basically completely destroyed, and the degree of freedom of the molecular chains had reached a high level, and the effect on the cross-linking degree was no longer significant.

The positive sulfurization time tc90 shows a trend of first decreasing and then increasing, and twin-screw has the highest efficiency in both types of processing. This indicates that after twin-screw processing, the processing efficiency of rubber can be improved, and the ideal degree of vulcanization can be achieved within a certain period of time. However, after 3-4 twin-screw cycles, excessive extrusion caused basic damage to the cross-linking structure of the WRP, leading to an increase in tc90 and a decrease in processing efficiency.

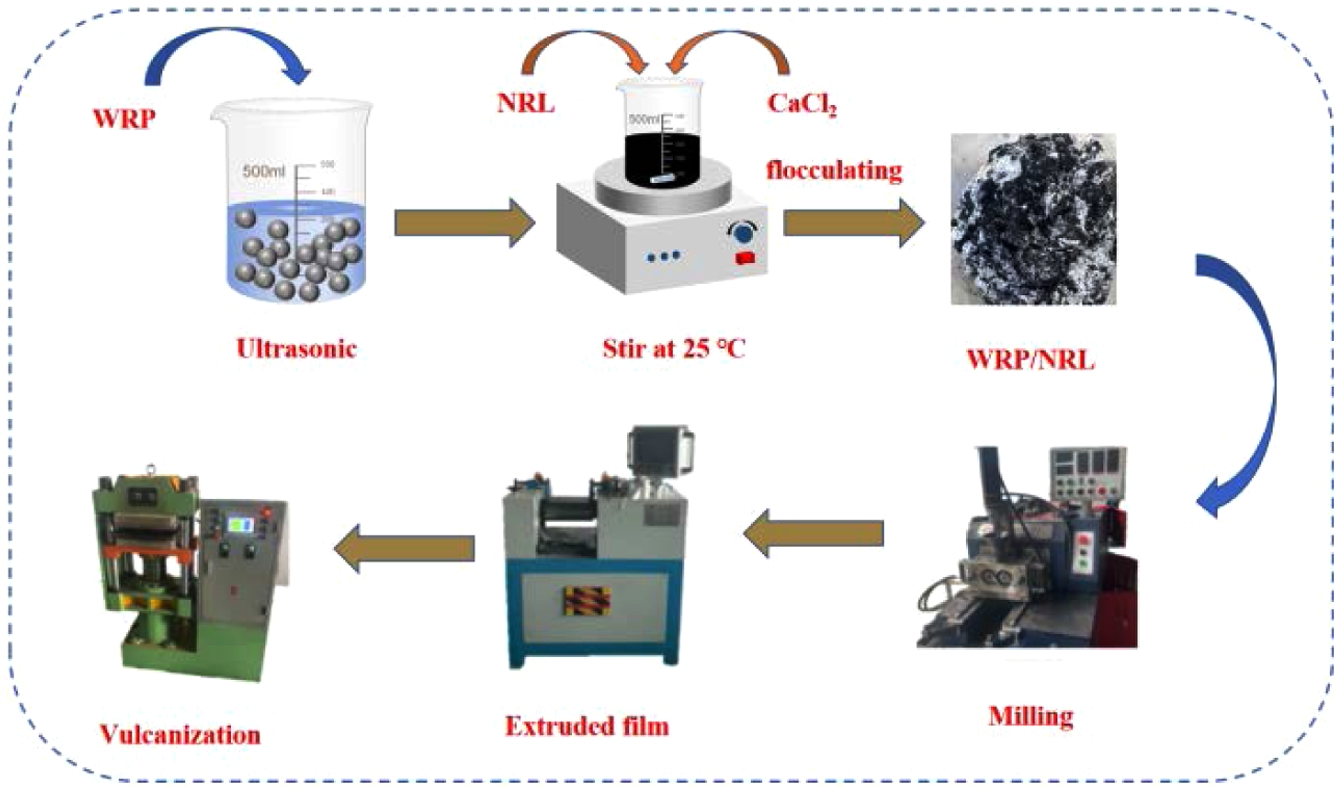

Mechanical Properties of NRL/WRP Composites. All experiments in this study were conducted with multiple independent replicates to ensure the reproducibility and reliability of the results. The error bars depicted in the figures clearly reflect the dispersion of data across multiple replicate tests. Furthermore, we rigorously selected multiple representative samples for testing in strict accordance with national standards to guarantee the comprehensiveness and stability of the experimental results. All analyses in the paper are based on the averages of multiple independent experiments.

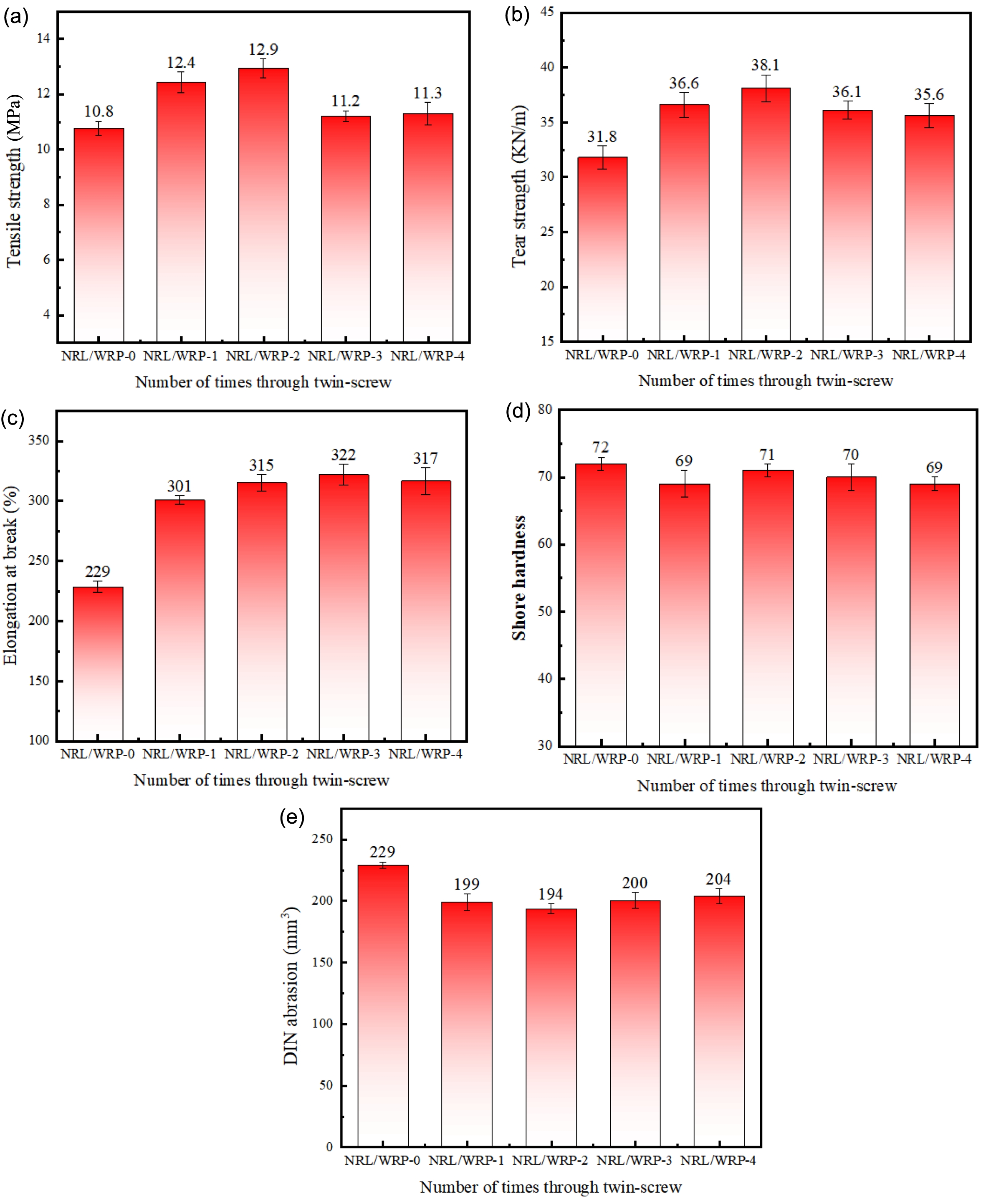

Figures 3(a), (b) and (c) show a significant improvement in the mechanical properties of rubber composite materials treated twice by a twin-screw extruder: Compared with the rubber material made from rubber powder without twin-screw, tensile strength increased by 19.44%, tear strength increased by 19.81%, and elongation at break increased by 37.55%. This improvement is mainly attributed to the degradation and surface activation effect of WRP by twin-screw extruder under high temperature and high shear. This treatment enhances the interfacial bonding between WRP and natural NR matrix. Following a twin-screw treatment, the WRP experiences bond-breaking desulfurization, leading to an augmentation in the quantity of polysulfide, disulfide, and monosulfide bonds within the vulcanized rubber, which in turn enhances its mechanical properties.19-21 However, compared with vulcanized rubber treated with twin-screw for three or four times, excessive high heat and high shear may cause strong degradation and surface activation of WRP, which to some extent destroys the main chain of rubber molecules and leads to a decrease in performance.22,23 However, after bond breaking desulfurization regeneration, the sulfur bond structure inside the vulcanized rubber is still improved. These two opposing effects interact with each other, ultimately improving the mechanical properties of the rubber material compared to untreated WRP.

In Figure 3(d), it can be observed that if the experimental results show that the hardness values of the WRP after desulfurization and regeneration by the twin-screw extruder are not significantly different at different extrusion times, all around 71, this indicates that the effect of extrusion times on hardness is not significant in this experiment. This is because the hardness of the rubber material mainly depends on the comprehensive effect of factors such as the vulcanization system, rubber formula, and processing technology, which can affect the degree of cross-linking and network structure of rubber molecular chains, thereby affecting the hardness of the rubber material. In this experiment, the same rubber formula, vulcanization system, and processing technology were used, and only the WRP in the formula was subjected to twin-screw regeneration. The effect on hardness was not significant, so the final change in hardness was not significant.

From Figure 3(e), it can be seen that compared to not regenerating through the screw, after two rounds of screw regeneration, the wear of the rubber material decreased by 15.28% and the wear resistance was improved. This indicates that compared to the WRP that has not been regenerated by twin-screw, the high heat and high shear of the extruder have a degradation and surface activation effect on the WRP, enhancing the interfacial bonding force between the WRP and the NR matrix. This leads to an increase in the internal polysulfide bonds, disulfide bonds, and monosulfate bonds of the vulcanized rubber material obtained after bond breaking desulfurization regeneration of the WRP by twin-screw. Therefore, the wear resistance of the obtained vulcanized rubber is improved. When passing through the screw multiple times, the screw extrusion causes damage to the main chain of rubber molecules.24-26 However, at the same time, the sulfurized rubber material obtained after bond breaking desulfurization regeneration has an increase in multiple sulfur bonds, disulfide bonds, and single sulfur bonds inside. Combining the two effects, the wear of the rubber material is increased, which partially improves its performance compared to the material without screw treatment.

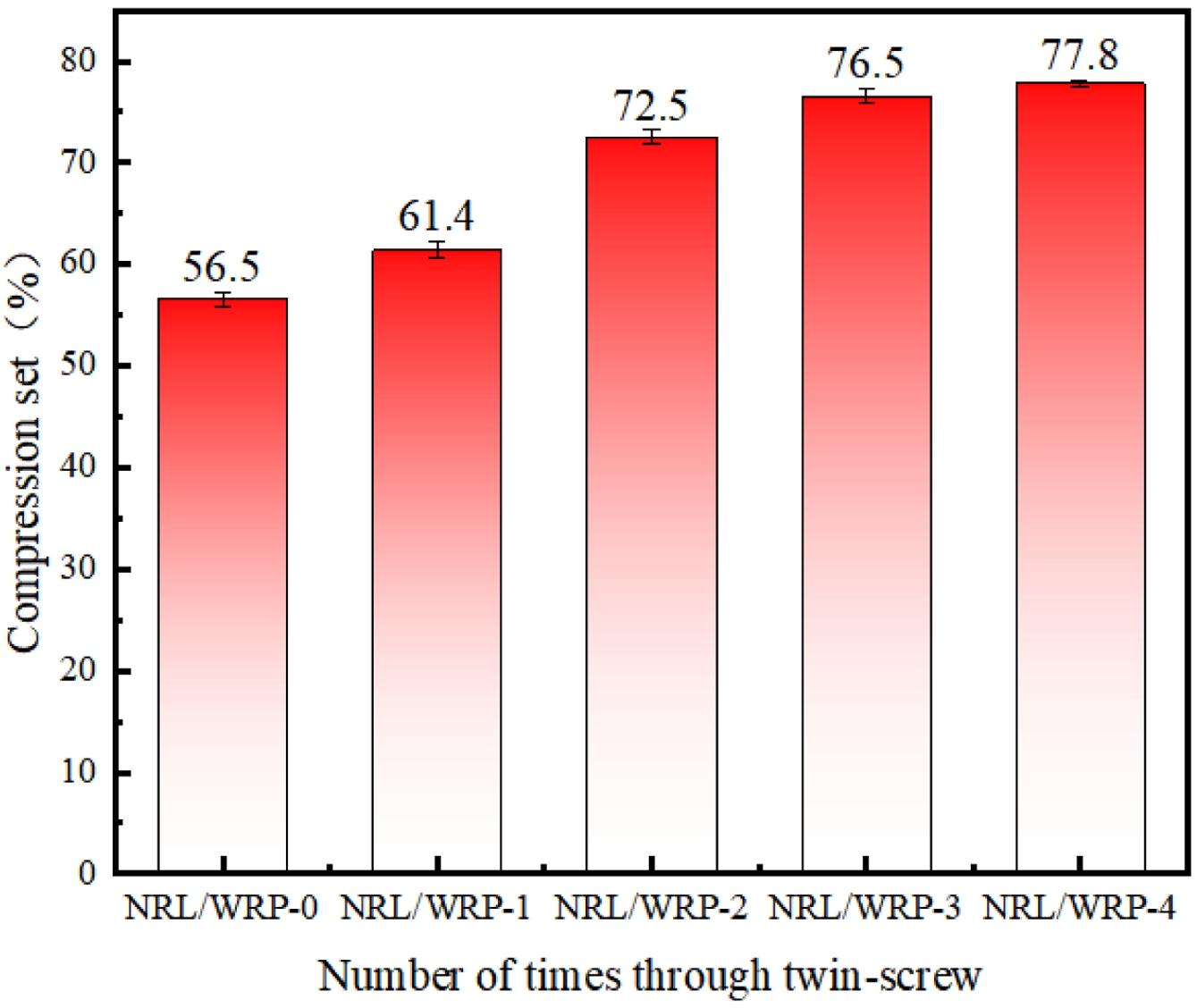

Compression permanent deformation test of NRL/WRP composite materials

. Figure 4 demonstrates that the compression permanent deformation of the rubber material increases with the number of screw passes. This trend is attributed to the increased likelihood of molecular chain breakage or degradation within the rubber matrix under the conditions of high temperature and shear that accompany multiple twin-screw extrusions. As the molecular chains degrade, their length shortens and their elasticity diminishes, which hinders the chains' ability to revert to their original state after being compressed, thereby amplifying the degree of permanent compression deformation.27 During the extrusion process, some sulfurized cross-linking bonds, such as polysulfides, may be compromised, leading to a reduction in cross-link density and a consequent decline in the rubber's elastic resilience. Additionally, excessive extrusion can induce secondary cross-linking or chain entanglement, creating uneven or rigid cross-linking networks. These cross-linked structures can restrict the flexibility of the molecular chains, impeding their recovery from compression. With each additional screw pass, the number of polysulfide bonds increases, making them more susceptible to breaking and forming new cross-linking bonds under compression. This dynamic results in significant compression and permanent deformation of the rubber material. In essence, the balance between the degradation of existing cross-links and the formation of new ones plays a critical role in determining the rubber’s resistance to permanent deformation.28

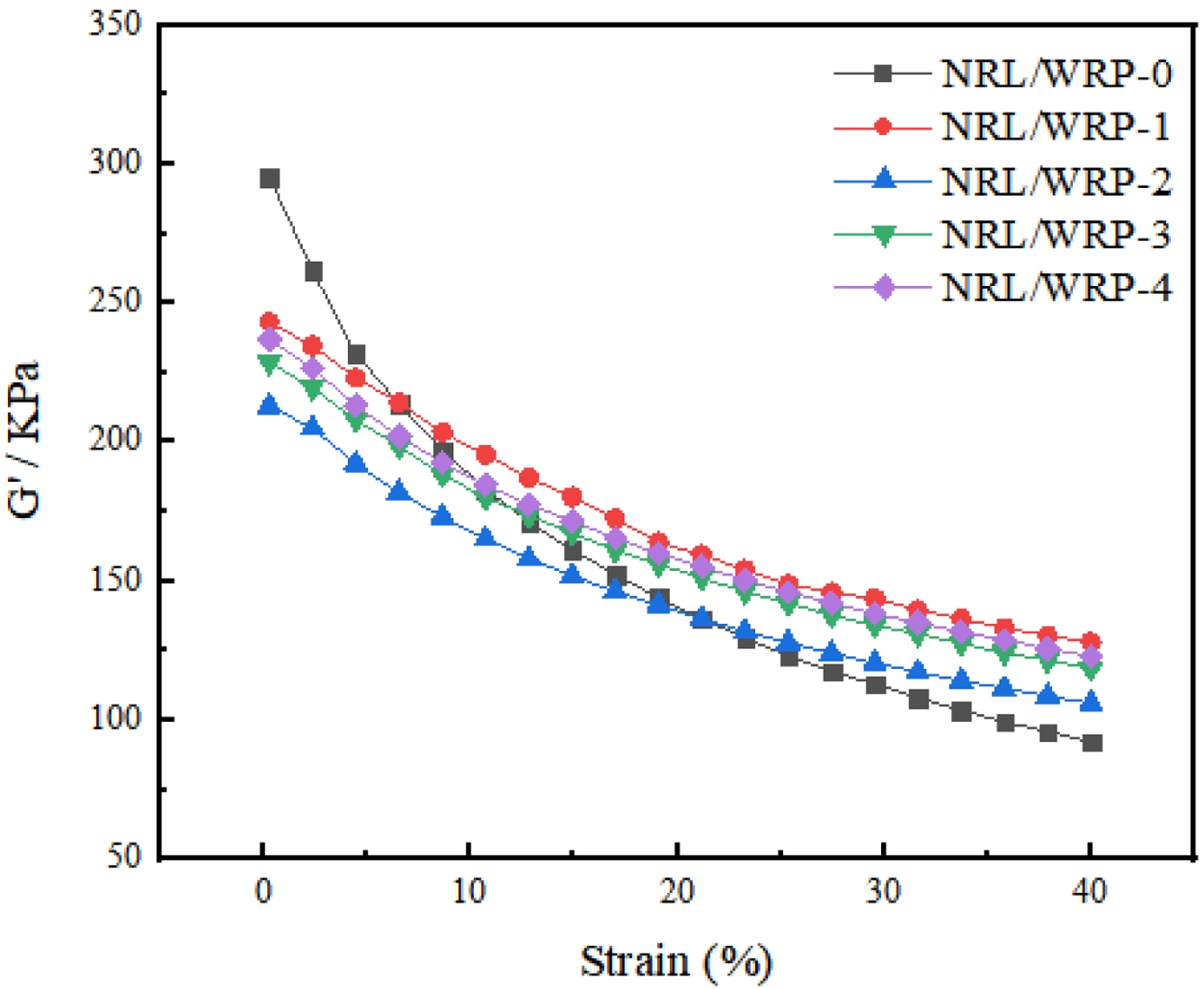

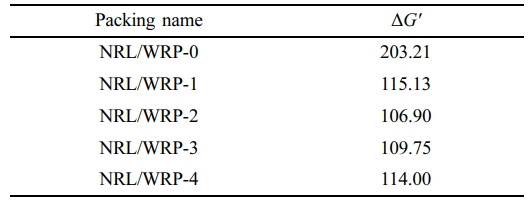

Processing Performance Analysis (RPA) of NRL/WRP Composites. The Rubber Process Analyzer (RPA) for the storage modulus stress curve of composite materials exhibits significant behavior within the strain range of 0-40%. Throughout the entire range, the storage modulus (G') gradually decreases, mainly due to the damage of the filler network structure. This phenomenon is called the Payne effect and is a characteristic of rubber composite materials under strain loading. The modulus difference (ΔG') is used to measure the magnitude of the Payne effect, filler dispersion, and network structure, and is calculated by subtracting the minimum value from the maximum G' value on each curve. Generally speaking, the smaller the ΔG' value, the better the material dispersibility.29 As shown in Table 3 and Figure 5, the ΔG' values of samples NRL/WRP-0 to NRL/WRP-4 are 203.21, 115.13, 106.90, 109.75, and 114.00, respectively. Among them, the NRL/WRP composite material without twin-screw regeneration has the highest ΔG' value, indicating the largest Payne effect and the worst dispersion of fillers in the rubber matrix; The Δ G' value of the rubber material modified by twin-screw surface decreases, and the ΔG' values for 1-4 times are all around 110, indicating a decrease in the Payne effect and better dispersion of the filler in the rubber matrix. Among them, the NRL/WRP composite material that has undergone two twin-screw regeneration processes has the smallest ΔG' value, indicating the best dispersion and performance. This indicates that the modified composite material exhibits excellent mechanical properties and filler dispersion during strain loading.

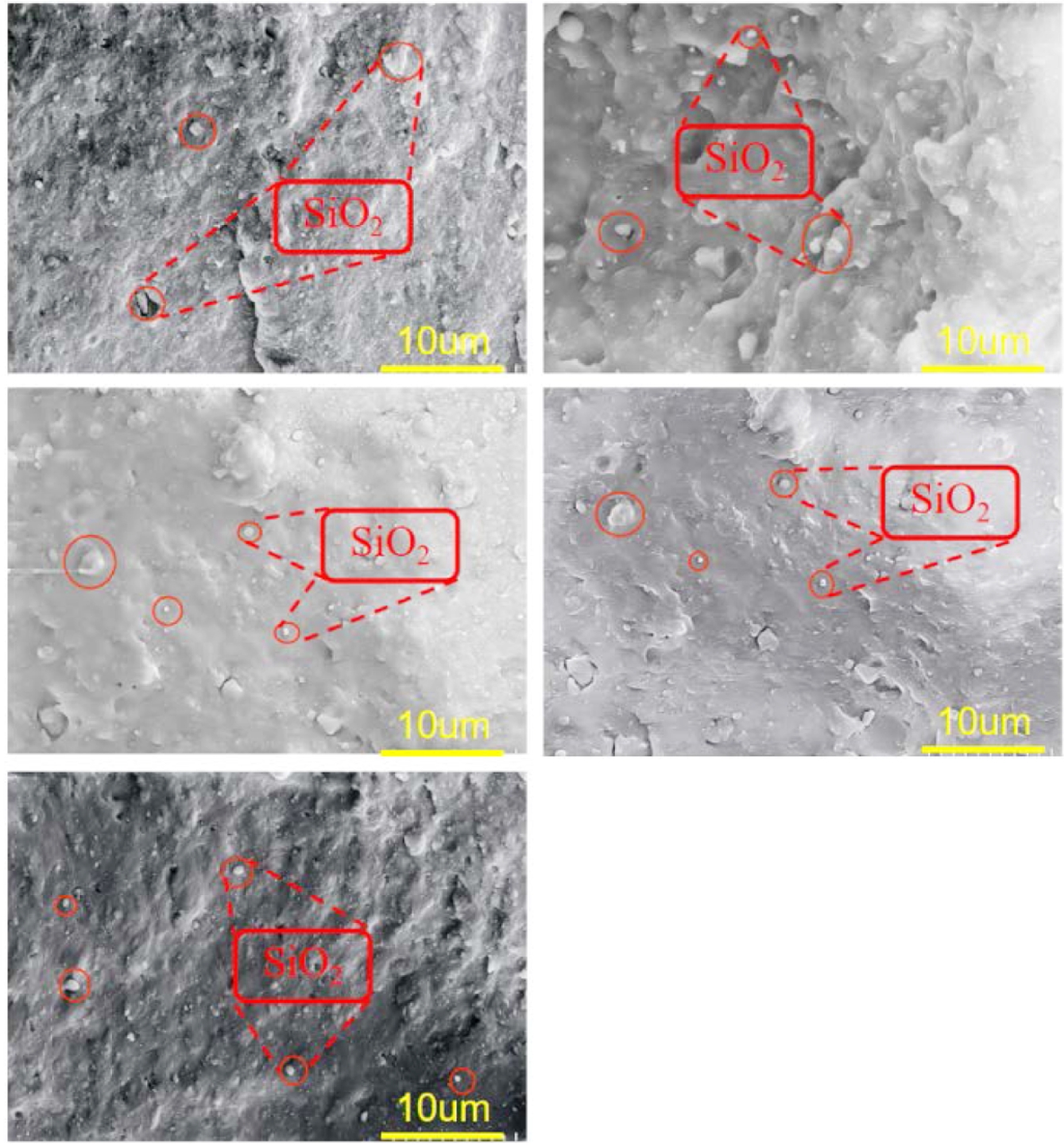

SEM of NRL/WRP Composites. The SEM image shown in Figure 6 provides insights into the microstructure of modified WRP and natural rubber composites.30 It is worth noting that the cross-section of the rubber sample in Figure 6(a) and (b) appears very rough, as shown by the red circle, with white carbon black clearly scattered on the surface, indicating uneven distribution of fillers. In contrast, the cross-section of the rubber sample in Figure 6(c) and (d) is smooth, with only a very small amount of white carbon black exposed. This indicates that the dispersion of the filler is more uniform. Although the cross-section of the adhesive in Figure 6(e) is relatively rough, there are fewer exposed fillers compared to 6(a) and (b).

These observations indicate that when rubber materials undergo 2-3 twin-screw modifications, the cross-section after fracture becomes smoother, and the filler (SiO2) tends to not aggregate, forming a continuous and uniform matrix. This means that compared to the samples in 6(a), (b), (e), the surface regeneration of WRP leads to the filling material (SiO2). Molecular chains can move more freely, forming a more uniform texture during the vulcanization process. However, after 4 cycles of twin-screw regeneration, excessive shear force can damage the original matrix, causing some fillers to re-aggregate and resulting in a decrease in filler dispersion. This indicates that although surface regeneration of WRP is beneficial, it is not necessarily better to regenerate more times. On the contrary, the optimal balance must be achieved to ensure the best dispersion and uniformity of the filler in the rubber matrix.

The numbers a in the figure is NRL/WRP-0; The numbers b in the figure is NRL/WRP-1; The numbers c in the figure is NRL/WRP-2; The numbers d in the figure is NRL/WRP-3; The numbers e in the figure is NRL/WRP-4.

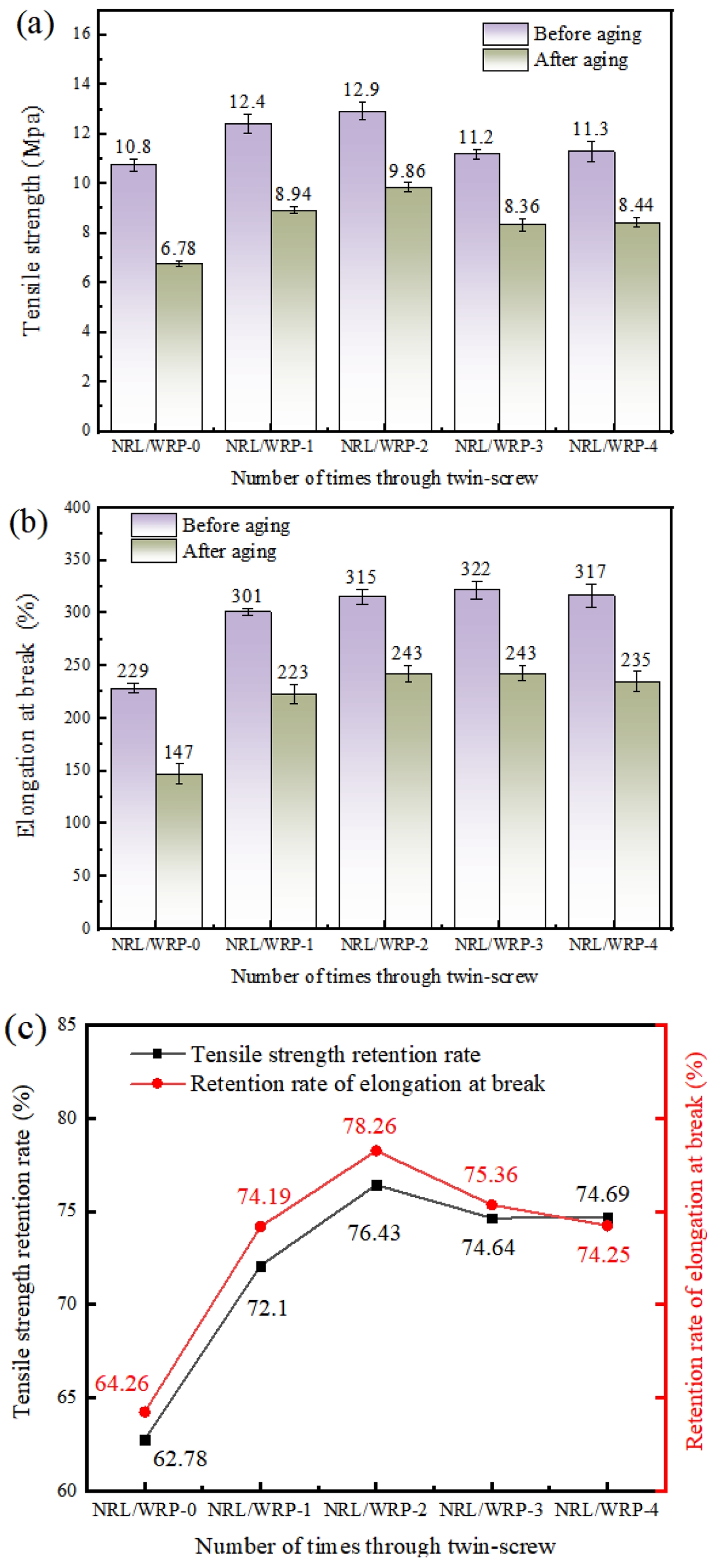

Aging Resistance of NRL/WRP Composites. Aging in rubber products is characterized by a decline in performance over time due to prolonged use. Microscopically, this deterioration is attributed to chemical reactions that occur within the rubber molecules and their associated compounds. The rate of aging performance change is quantified as the percentage difference in performance between aged and unaged rubber samples, relative to the initial performance value.31

From the data in Figure 7(c), it can be seen that the tensile strength retention rate and elongation at break retention rate of the rubber material produced by twin-screw are improved compared to those without twin-screw. This is because the original WRP retains a higher cross-linking density and tight molecular chain structure, which makes it more susceptible to external factors (such as heat, oxygen, light, etc.) during aging, leading to a decrease in performance. Indicating that twin-screw modification of WRP can improve its aging resistance. In the comparison of rubber materials with added WRP, the tensile retention rate of the rubber material with added WRP first increases and then decreases with the increase of the number of passes through the twin-screw. When passing through the twin-screw twice, the tensile strength retention and fracture elongation retention of the rubber composite material reach their maximum values, reaching 76.43% and 78.26%, respectively. From Figures 7(a) and (b), it can be seen that the tensile strength of the composite material reaches 9.86Mpa, and the elongation at break reaches 243%. This is because the mechanical shear and thermal effects of the extruder have destroyed some of the cross-linking bonds, reducing the cross-linking density. The degree of freedom of molecular chain is increased, the elasticity and ductility of rubber are improved, and the anti-aging ability is enhanced. After three and four cycles, both the tensile retention rate and the elongation at break retention rate slightly decreased. This is because excessive extrusion times may lead to excessive breakage of the WRP molecular chain, and may introduce new crosslinking reactions (such as thermal oxidation crosslinking), resulting in a slight decrease in aging performance.

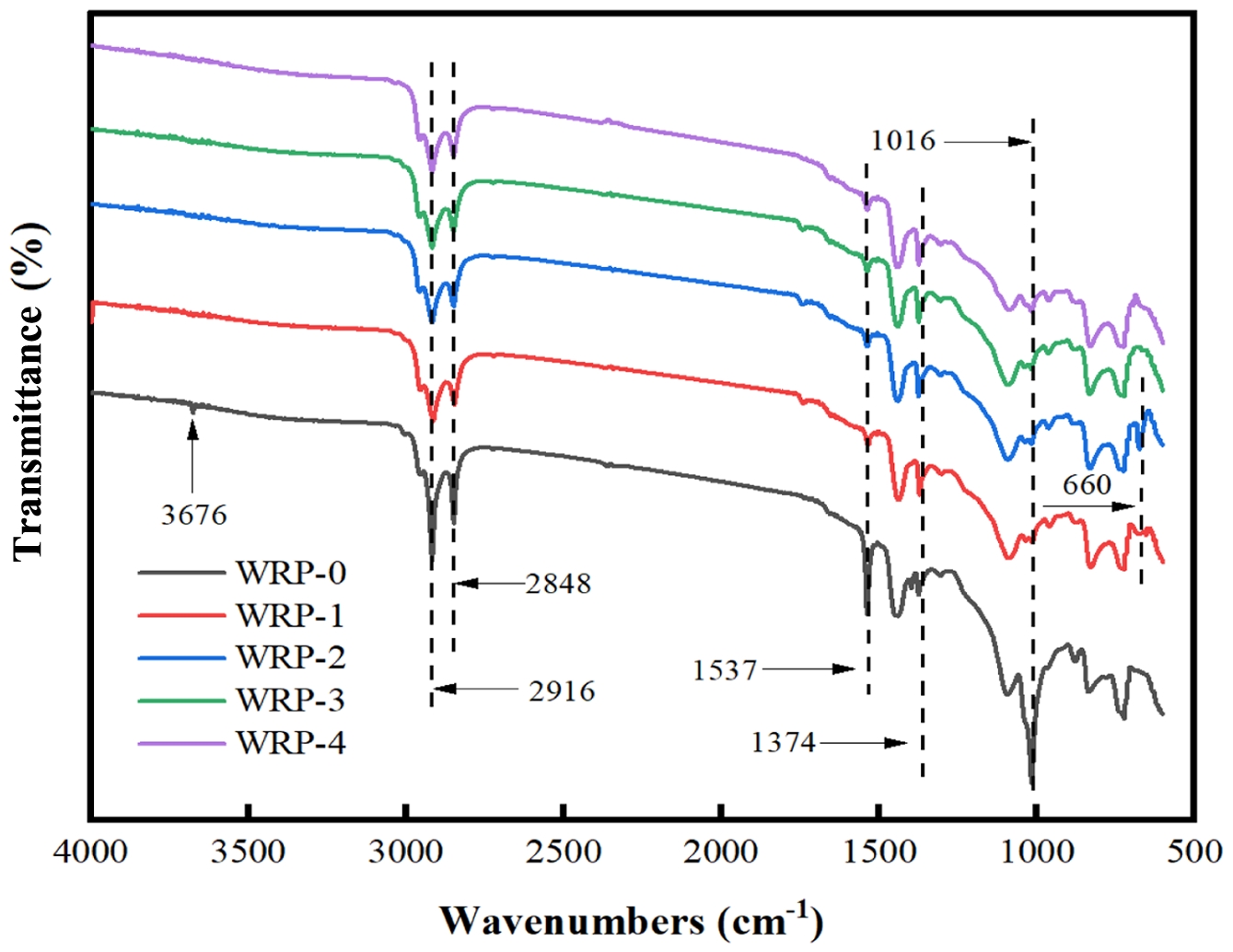

Analysis of Twin-Screw Extruded WRP. As shown in Figure 8, only WRP-0 exhibits a very weak peak at 3676 cm-1. This is attributed to other impurities (such as certain oxides) present in the original rubber powder, resulting in a faint absorption peak. At 2916 cm-1 and 2848 cm-1, all five rubber powder samples exhibit identical absorption peaks.32

These correspond to the absorption vibration peaks of saturated hydrocarbon bonds (C-H), arising from the stretching vibrations of C-H bonds. Simultaneously, absorption peaks at 2916 cm-1 and 2848 cm-1 gradually weakened with increasing cycles of desulfurization regeneration in the twin-screw extruder. This attenuation resulted from damage to the rubber molecule backbone, diminishing absorption of C-H related peaks. At 1537 cm-1, absorption peaks are present in all five rubber powder samples.33 However, as the number of desulfurization and regeneration cycles in the twin-screw extruder increases, this peak gradually weakens. This is related to the destruction of C=C (carbon-carbon double bonds). In waste rubber, C=C primarily originates from unsaturated double bonds in the rubber backbone. This indicates that during the twin-screw extruder desulfurization process, both the vulcanized cross-linked network and unsaturated double bonds are damaged, leading to the weakening of the C=C vibration peak. That is, while desulfurizing the rubber powder, the molecular backbone of the rubber is also disrupted, resulting in weakened absorption of both C=C and C-H related peaks. Concurrently, at 1374 cm-1, the absorption peak gradually intensifies with increasing desulfurization cycles in the twin-screw extruder.34 This enhancement stems from the symmetric stretching vibration of -CH3 (methyl) groups, indicating a relative increase in -CH3 content and a reduction in long-chain structures. This occurs because, during desulfurization, partial breakage of S-S bonds or C-C backbone chains in the WRP leads to increased branching or the formation of small-molecule alkanes, thereby enhancing the peak at 1374 cm-1. This trend aligns with the simultaneous weakening of peaks at 2916 cm-1 and 2848 cm-1 (C-H stretching vibrations).

Additionally, at 1016 cm-1, the absorption peak diminishes with increasing cycles of desulfurization regeneration in the twin-screw extruder.35 This reflects the breaking of Si-O crosslinks, consistent with the weakening trend at 1537 cm-1 (C=C vibration), indicating disruption of the rubber's crosslinked network. Furthermore, at 660 cm-1, no C-S bond was detected in WRP. A faint C-S-related peak appeared in powder after one twin-screw modification cycle, while the peak intensity significantly increased in powder after two twin-screw modification cycles. This indicates that moderate mechanical shearing and thermal treatment break polysulfide bonds in rubber powder to an appropriate extent, generating a suitable amount of active R-S radicals. During the third and fourth extrusion processes, no peak is visible at 660 cm-1, suggesting that active R-S radicals have been destroyed by excessive mechanical and thermal action,36

leading to high concentrations of radicals or partial radical self-association, which form stable, inactive molecules.

Simultaneously, it can be observed that the rubber powder regenerated via twin-screw extrusion (WRP-1, WRP-2, WRP-3, WRP-4) exhibits FTIR spectra similar to the original rubber powder (WRP-0), indicating no introduction of new substances or formation of new chemical bonds during this process.

Mechanism Explanation of NRL/WRP Composite Materials. During the screw extrusion process, the breaking of polysulfide bonds to form free radicals is a key reaction that directly affects the performance of the vulcanization stage.The following explains why the bonding performance between WRP extruded by screw once and natural rubber is better than that of WRP extruded by screw twice, from the two stages of extrusion and vulcanization.

As shown in Figure 9: During the screw extrusion process, the WRP is subjected to the combined effects of mechanical shear, high temperature, and friction, resulting in the breakage of polysulfide bonds (- S-S -)37 and the generation of sulfur free radicals (R-S).38 These free radicals have high reactivity and are important active substances involved in crosslinking reactions during the subsequent sulfurization stage.

In the first extrusion process, the mechanical shearing and heat treatment effects of the twin-screw were not fully utilized and only partially utilized; Resulting in suboptimal performance of the adhesive material; During the two extrusion processes, moderate mechanical shear and heat treatment break the polysulfide bonds in the WRP to an appropriate degree, generating an appropriate amount of active free radicals. In the subsequent vulcanization stage, these free radicals can effectively crosslink with molecules in natural rubber.39 During the 3rd and 4th extrusion processes, repeated mechanical and thermal actions lead to excessive breakage of polysulfide bonds in WRP, resulting in high concentrations of free radicals or partial free radicals self associating to form stable inactive molecules (such as peroxides or cyclic disulfides), reducing the total activity of free radicals and weakening the cross-linking effect in subsequent vulcanization stages.40

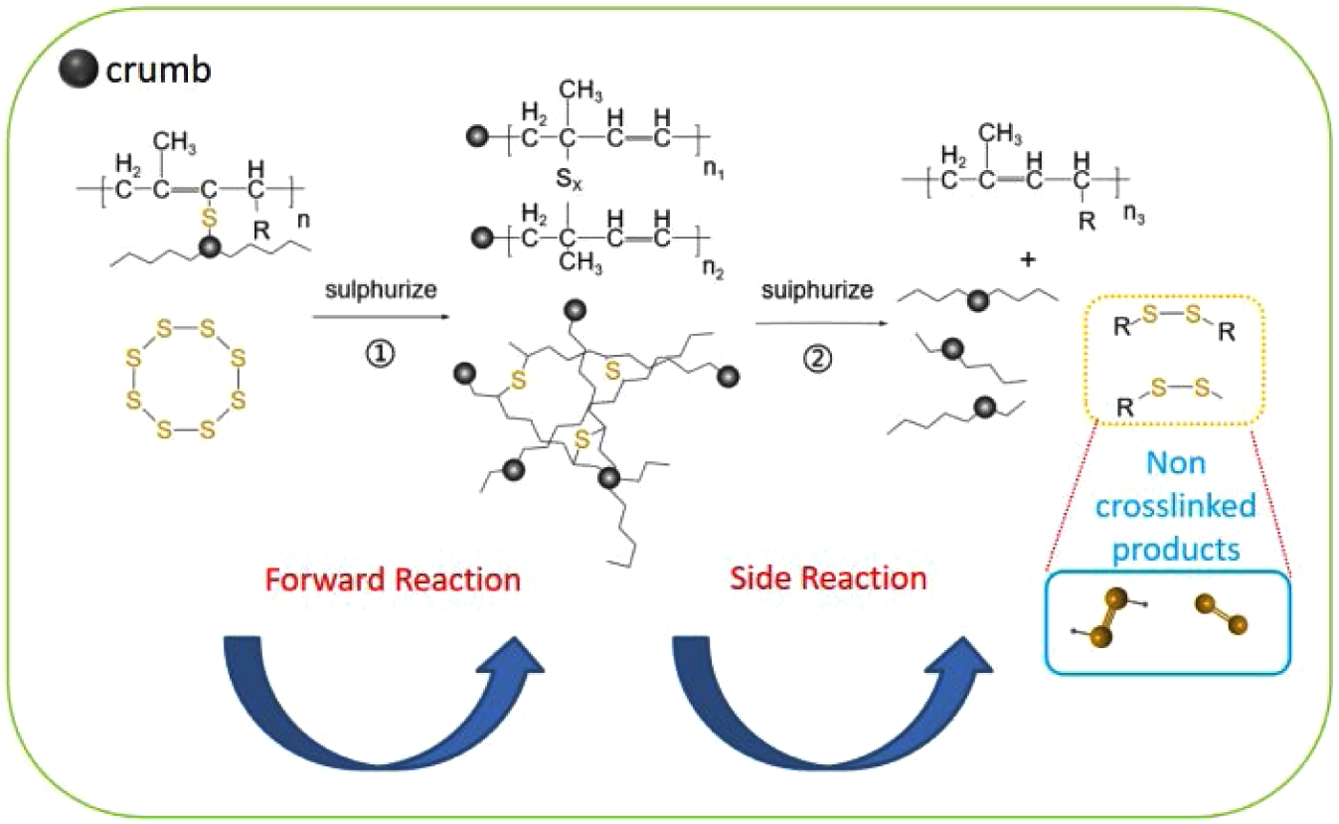

As shown in Figure 10: Double bond reaction between free radicals and natural rubber: Sulfur free radicals (R-S) can undergo addition reactions with carbon double bonds (C=C) on the molecular chain of natural rubber, forming new chemical bonds (C-S bonds). These cross-linking points significantly enhance the bonding performance between rubber powder and natural rubber. The extruded rubber powder provides an appropriate amount of highly active free radicals, which can fully participate in the reaction and form more chemical cross-linking points. Due to excessive processing, the number of active free radicals in the rubber powder extruded 3-4 times decreases or partially loses activity, resulting in a decrease in crosslink density and weakened adhesive performance.

Self association side reaction of free radicals: During the vulcanization stage, high concentrations of free radicals may undergo self association, generating non crosslinked products that cannot participate in the crosslinking reaction with natural rubber. Instead, these products competitively consume free radicals, reducing the actual crosslinking efficiency.

Decay of free radicals: Free radicals generated during 3-4 squeezing processes may be oxidized in heat treatment or air after squeezing, producing stable carboxyl, hydroxyl, or other inactive groups. Although these functional groups can improve physical adhesion, they cannot participate in crosslinking during the vulcanization stage, further weakening the adhesive properties of rubber powder.

In summary, the adhesive performance between the WRP extruded by the second screw and natural rubber is better than that of the WRP extruded by the first and third screw, mainly because the generation and activity of free radicals reach a relatively optimal equilibrium point in the second extrusion. Both non extrusion and excessive extrusion can lead to an imbalance of free radical activity, affecting the final vulcanization effect.

|

Figure 3 Mechanical properties of NRL/WRP composites: (a) tensile strength; (b) tear strength; (c) elongation at break; (d) shore hardness; (e) DIN abrasion. |

|

Figure 4 Compression set of NRL/WRP composites. |

|

Figure 5 G' curves of NRL/WRP composites. |

|

Figure 6 SEM of composites with different preprocessing methods. |

|

Figure 7 Aging performance of NRL/WRP composites: (a) tensile aging chart; (b) elongation at break aging chart; (c) tensile strength and elongation at break retention rate. |

|

Figure 8 FTIR analysis of twin-screw extruded WRP. |

|

Figure 9 Extrusion process of rubber powder. |

|

Figure 10 Sulfurization process of composite materials. |

Based on the above research results, we can conclude that compared with vulcanized rubber without twin-screw, the vulcanized rubber material obtained by surface modification with two screws through bond breaking and desulfurization regeneration of WRP has increased internal multi sulfur bonds, disulfide bonds, and single sulfur bonds, resulting in more free radicals and improved crosslinking degree. The tensile properties of NR/RRP composite materials increased by 19.44%, the tear strength increased by 19.81%, and the elongation at break increased by 37.55%. This indicates that secondary screw extrusion can effectively improve the dispersibility and interfacial bonding of WRP in natural latex matrix, thereby enhancing the overall mechanical properties of rubber. From an industrial perspective, industrialization can be achieved by grading and screening WRP, dynamically collecting key data during processing through real-time quality monitoring, feedback systems, and online monitoring equipment, feeding this data back to the production line, and optimizing compound formulations by adding appropriate amounts of stabilizers to enhance compatibility between WRP and natural latex.

- 1. Chen, B. H.; Zheng, D. H.; Xu, R. N.; Leng, S.; Han, L. L.; Zhang, Q. Q.; Liu, N.; Dai, C. N.; Wu, B.; Yu, G. Q.; Cheng, J., Disposal Methods for Used Passenger Car Tires: One of the Fastest Growing Solid Wastes in China. Green Energy & Environment 2022, 7, 1298-1309.

-

- 2. Wang, S. J.; Cheng, M. Q.; Xie, M.; Yang, Y. Y.; Liu, T. T.; Zhou, T.; Cen, Q. H.; Liu, Z. W.; Li, B., From Waste to Energy: Comprehensive Understanding of the Thermal-chemical Utilization Techniques for Waste Tire Recycling. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 115354.

-

- 3. Ahmed, K. Z.; Faizan, M., Comprehensive Characterization of Waste Tire Rubber Powder. J. Institution of Engineers (India): Series E 2024, 105, 11-20.

-

- 4. Ding, G. X.; Yang, J. N.; Duan, W. H., Modification and Application of Waste Rubber Powder. Asian J. Chem. 2013, 25, 5790-5792.

-

- 5. Liu, H. L.; Wang, X. P.; Jia, D. M., Recycling of Waste Rubber Powder by Mechano-chemical Modification. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 118786.

-

- 6. Liu, J. L.; Liu, P.; Zhang, X. K.; Lu, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M., Fabrication of Magnetic Rubber Composites by Recycling Waste Rubber Powders via a Microwave-assisted in situ Surface Modification and Semi-devulcanization Process. Chem. Eng J. 2016, 295, 73-79.

-

- 7. Lee, S. H.; Hwang, S. H.; Kontopoulou, M.; Sridhar, V.; Zhang, Z. X.; Xu, D.; Kim, J. K., The Effect of Physical Treatments of Waste Rubber Powder on the Mechanical Properties of the Revulcanizate. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 112, 3048-3056.

-

- 8. Guo, L.; Liu, G. X.; Bai, L. C.; Hao, K. F.; Zhao, J. Y.; Liu, K. X.; Jian, X. A.; Chai, H. L.; Liu, F. M.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H. C., Enhancing Interface Adhesion Between Waterjet-produced Rubber Powders and Natural Rubber by Wet-mixing Method. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55555.

-

- 9. Phumnok, E.; Khongprom, P.; Ratanawilai, S., Preparation of Natural Rubber Composites with High Silica Contents Using a Wet Mixing Process. Acs Omega 2022, 7, 8364-8376.

-

- 10. Dhenge, R. M.; Cartwright, J. J.; Doughty, D. G.; Hounslow, M. J.; Salman, A. D., Twin Screw Wet Granulation: Effect of Powder Feed Rate. Adv. Powder Technol. 2011, 22, 162-166.

-

- 11. Formela, K.; Cysewska, M.; Haponiuk, J., The Influence of Screw Configuration and Screw Speed of co-rotating Twin Screw Extruder on the Properties of Products Obtained by Thermomechanical Reclaiming of Ground Tire Rubber. Polimery 2014, 59, 170-177.

-

- 12. Lakhiar, M. T.; Kong, S. Y.; Bai, Y.; Susilawati, S.; Zahidi, I.; Paul, S. C.; Raghunandan, M. E., Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Concrete Incorporating Silica Fume and Waste Rubber Powder. Polymers 2022, 14, 4858.

-

- 13. Hao, K. F.; Wang, W. C.; Guo, X. R.; Liu, F. M.; Xu, Y.; Guo, S. Y.; Bai, L. C.; Liu, G. X.; Liu, M. M.; Guo, L.; Liu, H. C., High-value Recycling of Waste Tire Rubber Powder by Wet Mixing Method. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 135592.

-

- 14. Candau, N.; Leblanc, R.; Maspoch, M. L., A Comparison of the Mechanical Behaviour of Natural Rubber-based Blends Using Waste Rubber Particles Obtained by Cryogrinding and High-shear Mixing. Express Polym. Lett. 2023, 17, 1135-1153.

-

- 15. Kaliyappan, P.; Dhananchezian, M., Investigate the Effect of Ground Tyre Rubber as a Reinforcement Filler in Natural Rubber Hybrid Composites. Soft Materials 2023, 21, 129-148.

-

- 16. Innes, J. R.; Shriky, B.; Allan, S.; Wang, X.; Hebda, M.; Coates, P.; Whiteside, B.; Benkreira, H.; Caton-Rose, P.; Lu, C. H.; Wang, Q.; Kelly, A., Effect of Solid-state Shear Milled Natural Rubber Particle Size on the Processing and Dynamic Vulcanization of Recycled Waste Into Thermoplastic Vulcanizates. Sustainable Mater. Technologies 2022, 32, e00424.

-

- 17. Poovaneshvaran, S.; Hasan, M. R. M.; Jaya, R. P., Impacts of Recycled Crumb Rubber Powder and Natural Rubber Latex on the Modified Asphalt Rheological Behaviour, Bonding, and Resistance to Shear. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 234, 117357.

-

- 18. Vahdatbin, M.; Hajikarimi, P.; Fini, E. H., Devulcanization of Waste Tire Rubber via Microwave and Biological Methods: A Review. Polymers 2025, 17, 285.

-

- 19. Hassim, D.; Abraham, F.; Summerscales, J.; Brown, P., The Effect of Interface Morphology in Waste Tyre Rubber Powder Filled Elastomeric Matrices on the Tear and Abrasion Resistance. Express Polym. Lett. 2019, 13, 248-260.

-

- 20. Ren, T.; Song, P.; Yang, W.; Formela, K.; Wang, S. F., Reinforcing and Plasticizing Effects of Reclaimed Rubber on the Vulcanization and Properties of Natural Rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140.

-

- 21. Balasubramanian, M., Cure Modeling and Mechanical Properties of Counter Rotating Twin Screw Extruder Devulcanized Ground Rubber Tire-natural Rubber Blends. J. Polym. Res. 2009, 16, 133-141.

-

- 22. Sae-Oui, P.; Sirisinha, C.; Intiya, W.; Thaptong, P., Properties of Natural Rubber Filled with Ultrafine Carboxylic Acrylonitrile Butadiene Rubber Powder. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2011, 30, 183-190.

-

- 23. Shen, M.; Liu, J.; Xin, Z. X., Mechanical Properties of Rubber Sheets Produced by Direct Molding of Ground Rubber Tire Powder. J. Macromol. Sci. Part B: Phys. 2019, 58, 16-27.

-

- 24. Wang, J.; Zhang, K. Y.; Fei, G. X.; de Luna, M. S.; Lavorgna, M.; Xia, H. S., High Silica Content Graphene/Natural Rubber Composites Prepared by a Wet Compounding and Latex Mixing Process. Polymers 2020, 12, 2549.

-

- 25. Rezvani, M. H.; Sepahvand, S.; Ghofrani, M.; Fathi, L.; Ebrahimi, G., Development of Laminated Flooring Using Wood and Waste Tire Rubber Composites: A Study on Physical Mechanical Properties. Drvna Industrija 2024, 75, 107-119.

-

- 26. Wang, Z. F.; Yong, K.; Zhao, W.; Yi, C., Recycling Waste Tire Rubber by Water Jet Pulverization: Powder Characteristics and Reinforcing Performance in Natural Rubber Composites. J. Polym. Eng. 2018, 38, 51-62.

-

- 27. Sae-Oui, P.; Sirisinha, C.; Sa-nguanthammarong, P.; Thaptong, P., Properties and Recyclability of Thermoplastic Elastomer Prepared From Natural Rubber Powder (NRP) and High Density Polyethylene (HDPE). Polymer Testing 2010, 29, 346-351.

-

- 28. Kong, Y. R.; Chen, X. F.; Li, Z. X.; Li, G. X.; Huang, Y. J., Evolution of Crosslinking Structure in Vulcanized Natural Rubber During Thermal Aging in the Presence of a Constant Compressive Stress. Polym. Degradation and Stability 2023, 110513.

-

- 29. Nuinu, P.; Sirisinha, C.; Suchiva, K.; Daniel, P.; Phinyocheep, P., Improvement of Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of High Silica Filled Epoxide Functionalized Natural Rubber. J. Mater. Res. Technol. Jmr. T. 2023, 24, 2155-2168.

-

- 30. Kong, P. P.; Xu, G.; Fu, L. X.; Feng, H. X.; Chen, X. H., Chemical Structure of Rubber Powder on the Compatibility of Rubber Powder Asphalt. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 392, 131769.

-

- 31. Luo, M. C.; Liao, X. X.; Liao, S. Q.; Zhao, Y. F.; Fan, D.; Wang, L. Z., Waste Rubber Powder Modified by Both Microwave Treatment and Sol-gel Method and the Properties of Natural Rubber/modified Waste Rubber Powder Composites. Acta Polym. Sin. 2013, 7, 896-902.

-

- 32. Yu, L.; Liu, S. M.; Yang, W. W.; Liu, M. Y., Analysis of Mechanical Properties and Mechanism of Natural Rubber Waterstop After Aging in Low-Temperature Environment. Polymers 2021, 13, 2119.

-

- 33. Ikeda, Y.; Yasuda, Y.; Ohashi, T.; Yokohama, H.; Minoda, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Honma, T., Dinuclear Bridging Bidentate Zinc/Stearate Complex in Sulfur Cross-Linking of Rubber. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 462-475.

-

- 34. Intapun, J.; Rungruang, T.; Suchat, S.; Cherdchim, B.; Hiziroglu, S., The Characteristics of Natural Rubber Composites with Klason Lignin as a Green Reinforcing Filler: Thermal Stability, Mechanical and Dynamical Properties. Polymers 2021, 13, 1109.

-

- 35. Li, J. J.; Zhang, H. H.; Li, G. F.; Zhang, S. G.; Liu, Y.; Dong, K.; Zu, E. D.; Yu, L., Aging Mechanism Analysis of High Temperature Vulcanization Silicone Rubber Irradiated by Ultraviolet Radiation Based on Infrared Spectra. Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 2020, 40, 1063-1070.

- 36. Zhang, H. G.; Zhang, Y. P.; Chen, J.; Liu, W. C.; Wang, W. S., Effect of Desulfurization Process Variables on the Properties of Crumb Rubber Modified Asphalt. Polymers 2022, 14, 1365.

-

- 37. Kuzminskiĭ, A.; Lyubchanskaya, L., Processes Resulting from Thermal Rupture of the Sulfur Bonds in Vulcanizates. Rubber Chemistry and Technology 1956, 29, 530-533.

-

- 38. Zhang, X. Y.; Song, L. J.; Yu, R. B., The Property of a Novel Elastic Material Based on Modified Waste Rubber Powder (MWRP) by the Establishment of New Crosslinking Network. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 6929-6941.

-

- 39. Cataldo, F., Thermochemistry of Sulfur-Based Vulcanization and of Devulcanized and Recycled Natural Rubber Compounds. Int. J. Molecular Sci. 2023, 24, 2623.

-

- 40. Dellinger, B.; Lomnicki, S.; Khachatryan, L.; Maskos, Z.; Hall, R. W.; Adounkpe, J.; McFerrin, C.; Truong, H., Formation and Stabilization of Persistent Free Radicals. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2007, 31, 521-528.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2026; 50(1): 23-35

Published online Jan 25, 2026

- 10.7317/pk.2026.50.1.23

- Received on May 7, 2025

- Revised on Sep 14, 2025

- Accepted on Sep 29, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusion

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Huang, Yuan Jing* , and Guangyi Lin

-

College of Electromechanical Engineering, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, 266061, P. R. China

*Qingdao University of Science and Dongying, 257029, P. R. China - E-mail: qkgryjy@163.com, gylin666@163.com

- ORCID:

0009-0002-1249-221X, 0000-0001-8797-8607

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.