- Structure and Properties of Gelatin Hydrogels Immersed in Ammonium Ferric Citrate Solutions

Xiaomin Wang, Congde Qiao†

, Qian Lu, Qinze Liu, Wenke Yang†

, Qian Lu, Qinze Liu, Wenke Yang†  , and Jinshui Yao

, and Jinshui YaoSchool of Materials Science and Engineering, Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy of Sciences), Jinan 250353, PR China

- 구연산 철 암모늄 용액에 침지된 젤라틴 하이드로젤의 구조 및 물성

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

In this study, gelatin hydrogels were soaked in ammonium ferric citrate (AFC) solutions, and the effect of AFC content on the structure and properties of the as-prepared composite hydrogels was investigated in detail. The spectral data confirmed the formation of Fe-O and Fe-N bonds between Fe3+ and the amide groups of gelatin, and the hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions between gelatin chains were strengthened. Structural analysis suggested that the crystallinity of gelatin hydrogels was increased due to an introduction of ammonium ions and citrate ions. The tensile strength of gelatin hydrogels underwent a significant enhancement with an increase of AFC content, due to the existence of multiple crosslinks including triple helices and Fe3+ in hydrogels. Meanwhile, the fracture toughness was also increased by soaking treatment. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) results suggested that the composite hydrogels showed good freezing resistance, attributed to the strongly hydrated ammonium ions and citrate ions. These observations demonstrate that the structure and properties of gelatin composite hydrogels could be regulated by varying the AFC content.

A strong gelatin hydrogels with good anti-freezing performance was fabricated by immersing protein hydrogels in ammonium ferric citrate (AFC) solutions. Moreover, the structure-property relationship of immersed gelatin hydrogels was studied based on the Hofmeister effect and multivalent ionic cross-linking effect. The observations demonstrate that the structure and properties of protein composite hydrogels could be regulated by varying the AFC content.

Keywords: gelatin, composite hydrogels, freezing resistance, hydrogen bonds

The work was financially supported by the Natural Science Funds of Shandong Province (No. ZR2023ME152), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22578236).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Gelatin has good biocompatibility and biodegradability. In addition, this protein possesses excellent gelling properties, which is closely associated with its widespread application. However, the gelatin hydrogels have inherent disadvantages such as low mechanical strength, insufficient thermal stability, and poor anti-freezing properties,1-3 which greatly limit their applications in areas of tissue engineering and biosensors. Thus the modification of gelatin hydrogels is urgent to meet the application requirements, especially in low-temperature conditions.4

The methods to enhance the tensile strength of gelatin hydrogels are mainly divided into chemical methods and physical methods. Among them, chemical crosslinking is an effective approach for the strengthening of gelatin hydrogels.5-7 Nonetheless, the potential toxicity of residual cross-linking reagents may restrict their applications in biological and medical fields. In addition, the mechanical strength of gelatin hydrogels can be enhanced through blending with other components. For example, the introduction of k-carrageenan, linear poly(methyl methacrylate), graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets, and carbon nanotubes into the matrix could reinforce gelatin hydrogels.8-11 Moreover, it has been demonstrated that a double-network (DN) structure can endow the hydrogel with simultaneously enhanced strength and toughness based on multiple energy dissipation mechanisms.12-14 Several gelatin-based DN hydrogels have been reported in previous literature, mainly including gelatin/sodium alginate,15 gelatin/chitosan,16 gelatin/glycyrrhizic acid,17 gelatin/polyacrylamide,18 and gelatin/pHEAA19 double-network hydrogels. However, these approaches usually involve cumbersome experimental steps or complex chemical reactions. Furthermore, some of these enhanced hydrogels are generally not biocompatible or biodegradable, and may carry potential side effects during use.

Recently, a simple yet effective immersion method has been widely applied to enhance the mechanical strength of gelatin hydrogels.1,20-24 For instance, the immersion of pure gelatin hydrogels in (NH4)2SO4 solutions could obtain strong and tough hydrogels with a tensile strength of 3 MPa and an elongation at break of 500%, respectively.1 Similar results were observed in gelatin-based DN hydrogel systems.4,25 In addition, the soaking treatment of gelatin hydrogels with sodium citrate (Na3Cit) solutions resulted in a significant enhancement of both tensile strength and toughness.20,23 In these studies, the strengthening of immersed gelatin hydrogels is generally associated with the Hofmeister effect.20 A recent study found that the Hofmeister effect could be used to enhance effectively the mechanical strength of polyisocyanide hydrogels without changing their microstructure.26 Although it is generally accepted that the kosmotropic ions can significantly improve the mechanical strength of gelatin hydrogels, the strengthening mechanism is still controversial. Some authors attributed it to the hydrophobic interactions between gelatin molecules,1 whereas others ascribed it to the electrostatic interactions between gelatin and kosmotropic ions.27 Therefore, the molecular mechanism behind this ion-specific effect remains unclear.28

In addition to the Hofmeister effect, ionic crosslinking can also effectively regulate the structure and properties of gelatin hydrogels. The mechanical properties of gelatin hydrogels could be improved significantly with multivalent metal ions. For instance, Wang et al.29 studied the immersion of gelatin hydrogels in FeCl3 solutions, and found that the compression strength and strain reached up to 65 MPa and 99%, respectively. In addition, a novel double-network hydrogel was obtained by the addition of Fe3+ into PVA/PA mixtures through metal coordination bonds as well as hydrogen bonding, and the mechanical strength of as-prepared hydrogels was significantly improved.30 Moreover, this strengthening phenomenon was also observed in a P(AM-AA)-Fe3+ physical hydrogel system.31

The freezing of water is generally hindered by the introduction of salts due to the ion hydration effect, resulting in an improved freezing resistance of hydrogels.32 For instance, Morelle et al.33 found that the immersion of SA/PAM double-network hydrogels in calcium chloride solutions could effectively improve their frost resistance, and their freezing temperature could reach as low as -57 ℃. This strategy has been used in the gelatin system to improve its anti-freezing performance. It was reported that the introduction of sodium chloride could endow gelatin/polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels with excellent flexibility at -20 ℃.34 Recently, it was reported that the freezing point of gelatin/polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels decreased to -46.3 ℃ with the addition of (NH4)2SO4.35

The introduction of kosmotropic ions inevitably affects the interactions between gelatin chains, such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, and further influences the structure as well as properties of the hydrogels. In addition, the strong coordination interactions between gelatin and multivalent metal ions can also cause changes in protein structure and properties. However, there is a lack of systematic studies on the influences of kosmotropic ions as well as multivalent ions on the structure-property relationship of gelatin hydrogels. Ammonium ferric citrate is highly soluble in water and can produce kosmotropic citrate and ammonium ions as well as multivalent ferric ions. Thus, a deep understanding of how these ions influence the structure and properties of gelatin hydrogels at the molecular level is of great importance.

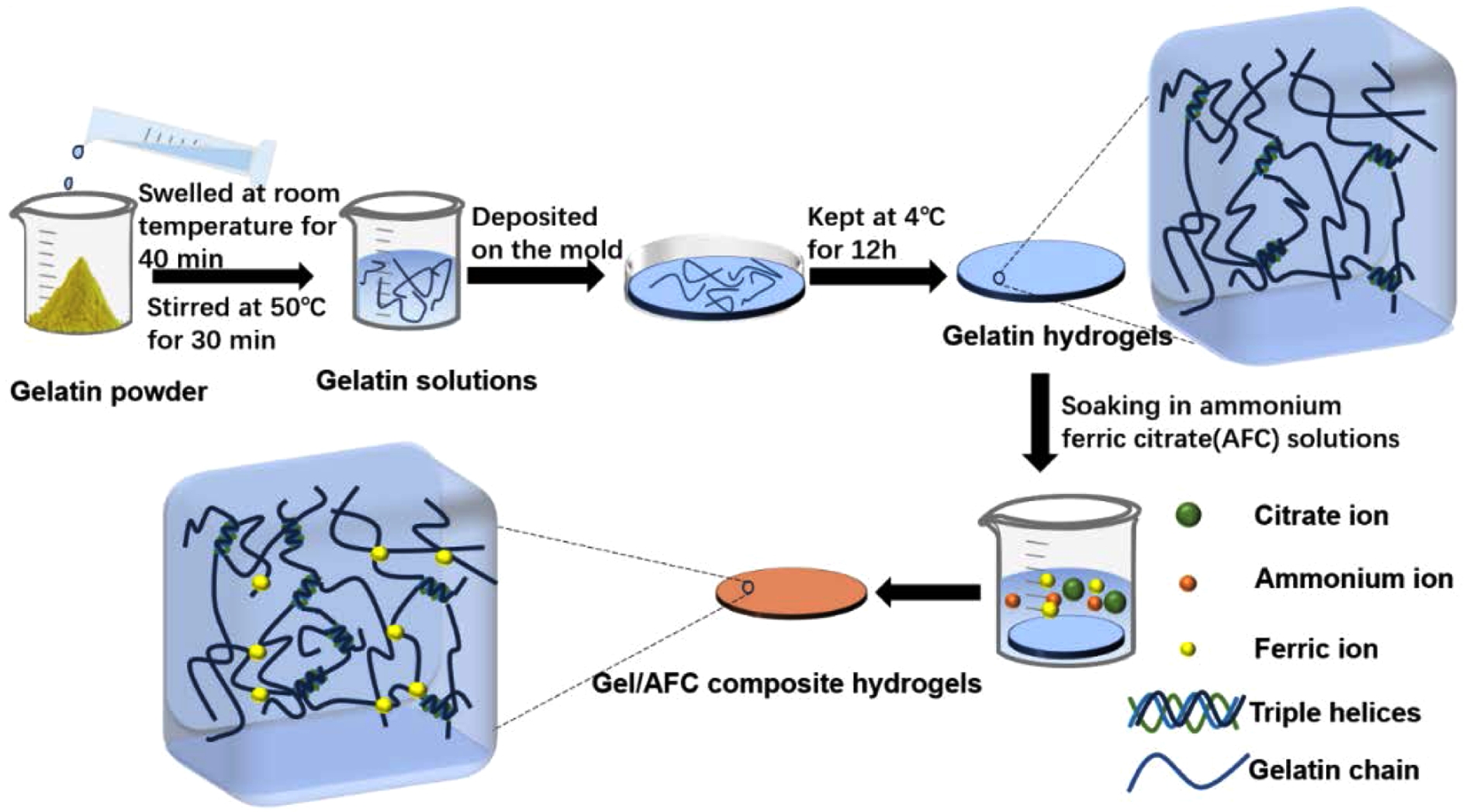

In this study, strong gelatin hydrogels with good anti-freezing performance were fabricated by immersing gelatin hydrogels in ammonium ferric citrate (AFC) solutions (Scheme 1). The effects of AFC content on the structure, mechanical properties, and freezing resistance of gelatin hydrogels were investigated in detail. In addition, the structure-property relationship of immersed gelatin hydrogels was studied based on the Hofmeister effect and multivalent ionic cross-linking effect. This work aims to reveal the strengthening mechanism of gelatin hydrogels at the molecular level, and to provide theoretical guidance for the design and development of gelatin-based hydrogel material with desirable performances.

Scheme 1. Schematic illustration of the preparation of gelatin/AFC composite hydrogels.

Materials. Gelatin (type B, ~220 Bloom) and ammonium ferric citrate (AFC) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (China), and were used without further purification. In addition, ultrapure water (17.44 MΩ) was obtained from an ultra-pure water system (Sichuan ULUPURE Ultrapure Technology Co., Ltd, China).

Preparation of Gelatin Hydrogels. First, a 10 wt% gelatin solution was prepared as follows: a certain amount of gelatin powder was dispersed in ultra-pure water, and swelled at room temperature (RT) for 40 min, subsequently, it was stirred at 50 ℃ for 30 min, and then a transparent gelatin solution was obtained. Second, this gelatin solution was deposited onto a Teflon mold, and kept at 4 ℃ for 12 h to form the original gelatin hydrogels.

Preparation of Gelatin/ammonium Ferric Citrate (AFC) Composite Hydrogels. The gelatin/ammonium ferric citratecomposite hydrogels were fabricated by the soaking method. Briefly, a series of ammonium ferric citrate solutions with different concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 g/mL could be obtained by dissolving a certain amount of AFC in ultra-pure water. Then the original gelatin hydrogel was soaked in AFC solutions at various concentrations (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 g/mL), afterwards, the immersed hydrogels were taken out, rinsed with ultra-pure water to remove surface residues and the gelatin/AFC hydrogels were formed. For convenience, the gelatin/AFC hydrogels are denoted as Gel/AFC-x, where Gel represents gelatin, AFC is ammonium ferric citrate, and x stands for the AFC concentration.

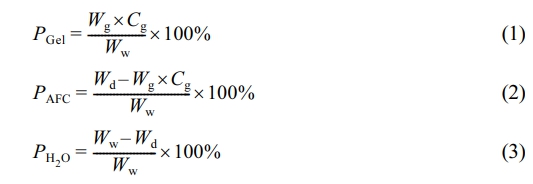

Characterization. The Composition of Gel/AFC-x Hydrogels: The gelatin content (PGel), AFC content (PAFC), and water content (PH2O) of Gel/AFC-x hydrogels were determined by Equations (1), (2) and (3), respectively, where Wg was the mass of pure gelatin hydrogel, Cg was the gelatin concentration (10 wt%). In addition, Ww and Wd were the masses of immersed hydrogels and corresponding dry gels (kept in a vacuum oven for 48 h at 60 ℃), respectively.

Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy. The ATR-FTIR experiments were conducted on a Nicolet iS20 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, USA). The FTIR spectra were collected in a wavenumber region of 400-4000 cm-1 at a resolution of 4 cm-1 during 16 scans.

Anti-freezing Experiments: All the hydrogel samples were stored in refrigerators at -22 ℃, and kept for 48h. Subsequently, the anti-freezing properties of hydrogels were examined by visual analysis as well as manual deformation.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): The XPS experiment was carried on an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (ESCALAB250Xi, USA) to explore the chemical composition of the gel samples. Prior to the XPS experiment, the gelatin/AFC hydrogels were freeze-dried and the dry gel samples were used for the XPS experiment.

X-ray Diffraction (XRD): To explore the microstructure of the hydrogel samples, XRD experiments were performed on a SmartLab SE X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Co., Ltd, Japan), equipped with a multi-channel detector via utilizing a Cu Kα1 (λ = 0.1542 nm) monochromatic X-ray beam. All hydrogel samples were characterized in the 2θ range of 5~50° with a scanning rate of 20°/min.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): The DSC experiment was carried out with a Q2000 DSC (TA Instrument, USA). The hydrogel sample with a mass of approximately 5~10 mg was hermetically sealed in an aluminum pan. The sample was first equilibrated at 10 ℃ and then heated to 50 ℃ with a rate of 10 ℃/min. Moreover, the low-temperature DSC experiment was performed to characterize the anti-freezing properties of hydrogel samples. Briefly, the hydrogel sample was first equilibrated at -80 ℃, and then heated to 40 ℃ with a rate of 5 ℃/min. Each sample was tested at least three times.

Tensile Testing: The tensile experiment of the hydrogel samples was carried out on a WDL-005 electronic universal testing machine (New Century Experimental Instrument Co., Ltd., Jinan, China). Briefly, the hydrogel sample was cut into rectangular strips with a length of 40 mm and a width of 5 mm. The experiment was conducted with a constant tensile rate of 50 mm/min. Each hydrogel sample was tested at least five times.

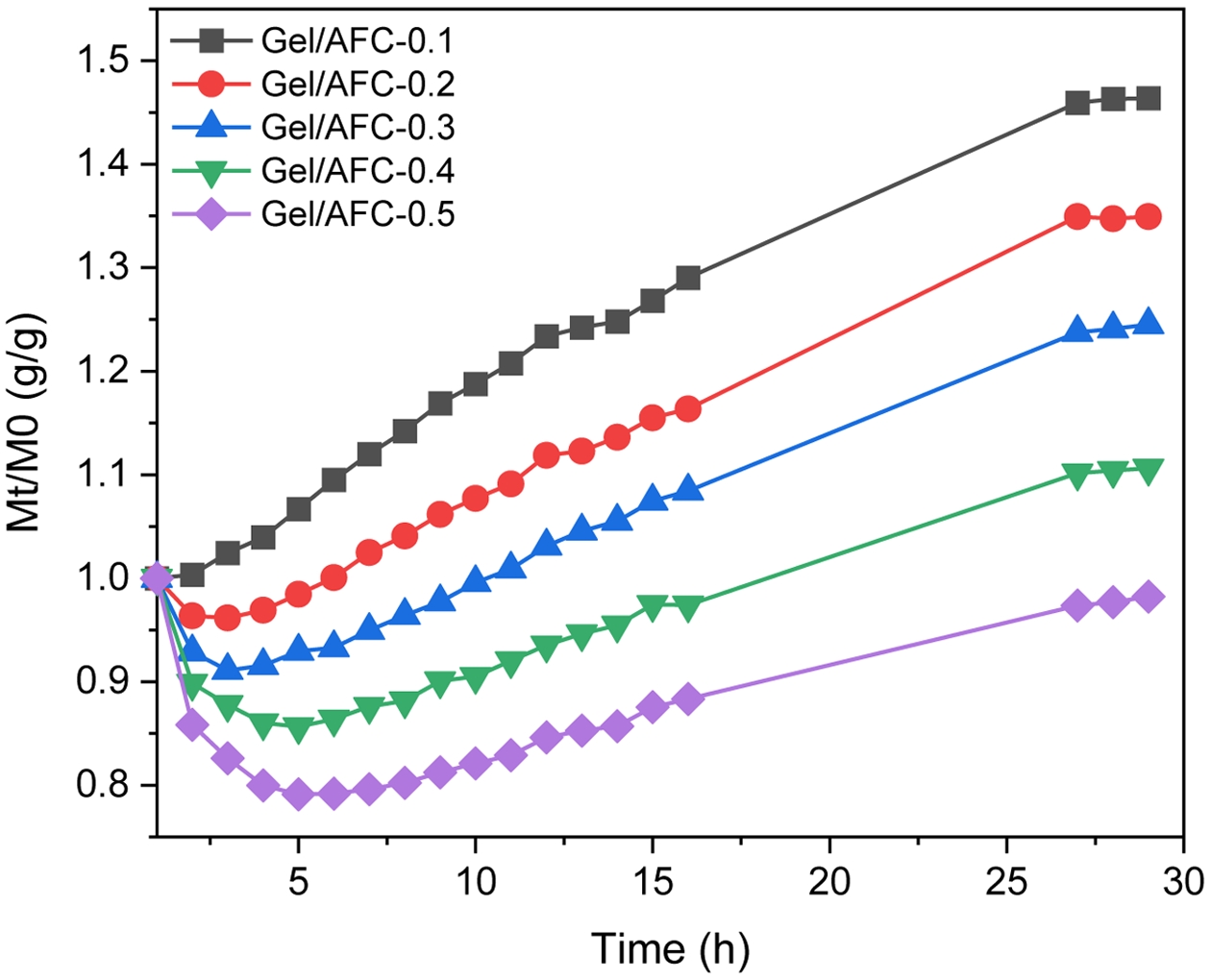

The Composition of Gel/AFC-x Composite Hydrogels. The dependence of hydrogel weight on immersion time in AFC solutions at different concentrations is displayed in Figure 1. It is seen that the weight of all composite hydrogels is nearly invariable at around 26 hours, indicating that the diffusions of salt ions in soaking solutions and water molecules in hydrogels tend to equilibrium. Moreover, the relative weight of immersed hydrogels gradually decreased with an increase in AFC concentration. For example, the hydrogel sample swelled in a 0.1 g/mL AFC solution, and its weight was increased by about 45%, which was raised by only about 10% in a 0.4 g/mL AFC solution. When the hydrogel was soaked in a 0.5 g/mL AFC solution, its weight decreased by about 5%, suggesting that the hydrogel dehydrated and shrank. The dehydration of gelatin hydrogels was observed in K3Cit solution with high concentration.20 The swelling and deswelling of the gelatin hydrogels may be related to different osmotic pressures of gelatin hydrogels and the AFC solutions. A similar observation was reported for the immersion of gelatin hydrogels in a deep eutectic solvent (DES).36 Interestingly, except for Gel/AFC-0.1 hydrogel, other hydrogel samples underwent an initial shrink and then a swelling at the early immersion stage. This may be associated with the different diffusion rates of water molecules and salt ions. Similar results were also observed for the Ca-alginate/PAAm hydrogels immersed in a glycerol solution.37

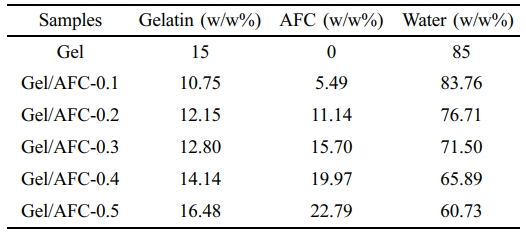

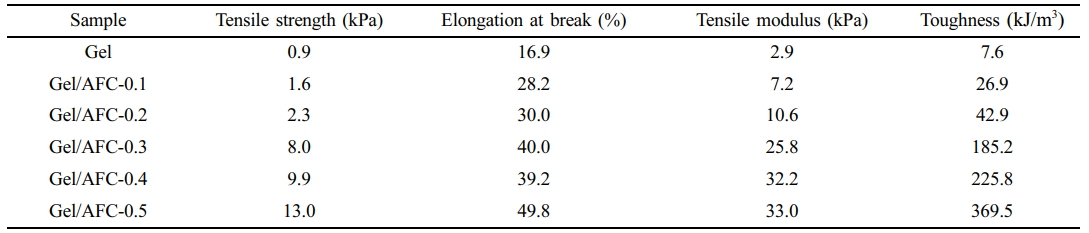

The component content of Gel/AFC-x hydrogels is displayed in Table 1. With an increase in the concentration of immersion solutions, the AFC content of hydrogels increased continuously and the gelatin content showed a similar change. On the contrary, the water content decreased with an increase of AFC solution concentration. This may be due to the absorption and swelling of the AFC solution. Similar results have been observed in the immersion of gelatin hydrogels in K3Cit solutions.20

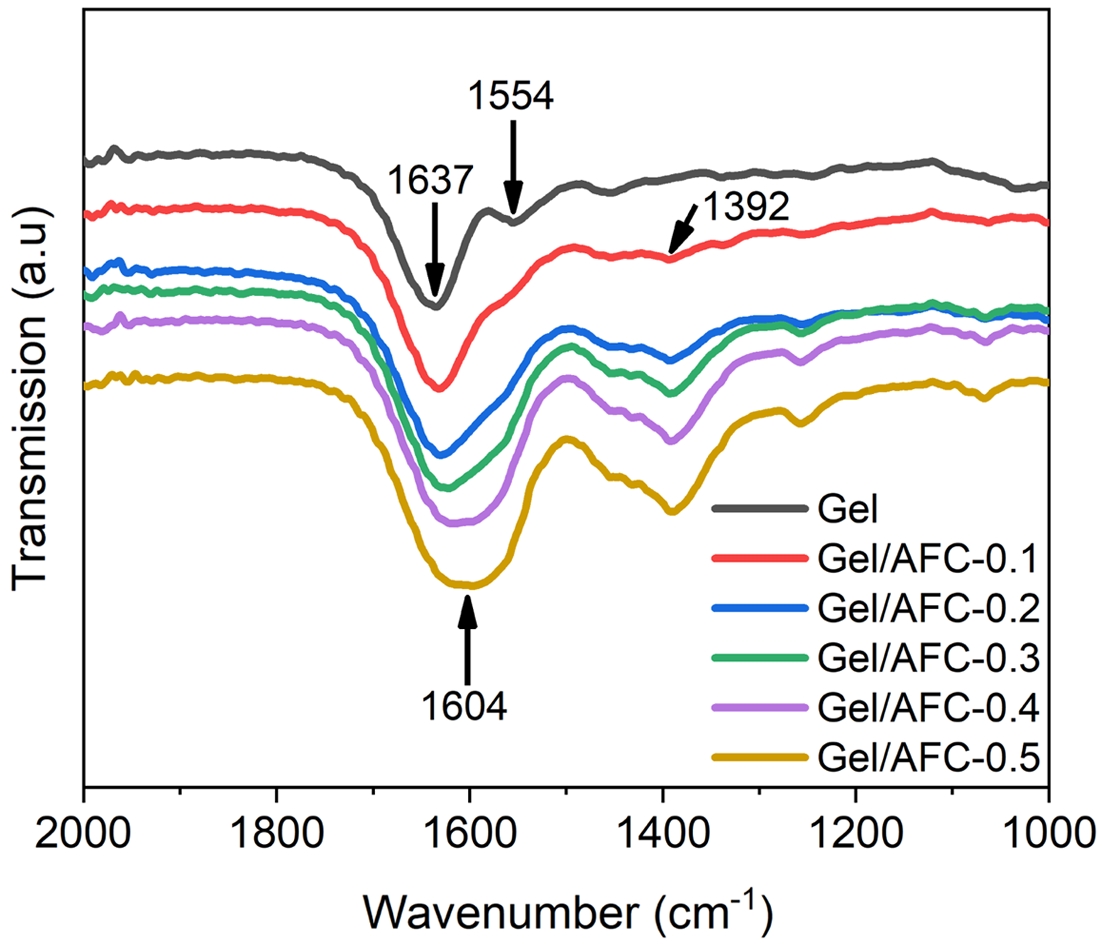

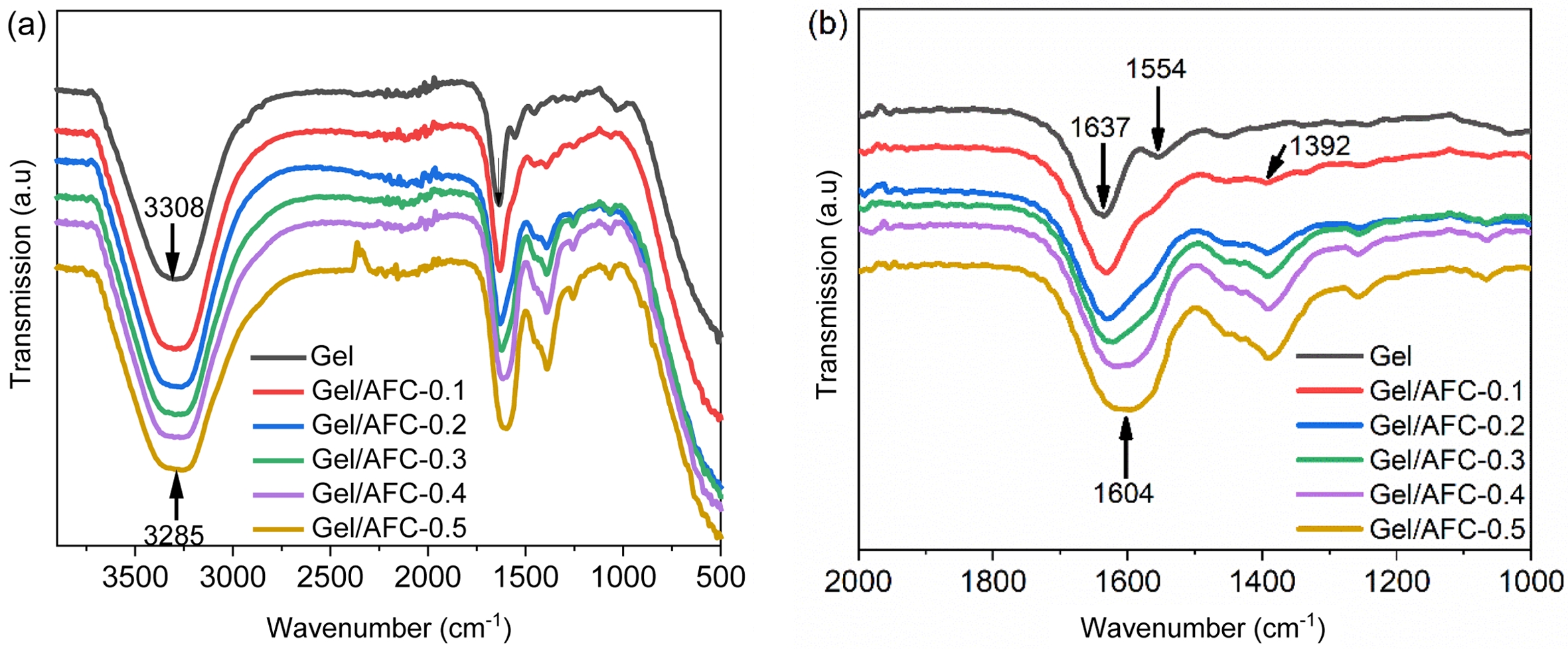

Molecular Interactions in Gel/AFC-x Composite Hydrogels. The FTIR spectra of gelatin and immersed hydrogels are shown in Figure 2. It can be seen that three main characteristic peaks locate at 3308 cm-1, 1637 cm-1, and 1554 cm-1 in the gelatin hydrogel. The broad characteristic peak that appeared at 3308 cm-1 was associated with the stretching vibration overlap of -NH and -OH groups, suggesting the existence of a large number of hydrogen bonds in the gelatin hydrogel. In addition, the characteristic absorption peak at 1637 cm-1 belonged to the amide I band, corresponding to the stretching vibration of C=O in gelatin, while the characteristic absorption peak at 1554 cm-1 was assigned to the amide II band, attributing to the bending vibration of N-H groups.

After the hydrogels were immersed in ammonium iron citrate solutions, the characteristic absorption peak at 3308 cm-1 broadened slightly and shifted gradually towards lower wavenumbers with the increasing of AFC concentration. For instance, this absorption peak shifted to 3285 cm-1 for the Gel/AFC-0.5 hydrogel. The red shift of this absorption peak suggests that the hydrogen bonding is enhanced by immersion of the hydrogels.38 A similar observation was reported for the immersed gelatin hydrogels in DES solutions.36 Moreover, the amide I band at 1637 cm-1 was broadened significantly and showed an apparent red shift with increasing AFC content, which shifted to low wavenumbers of 1604 cm-1 for the Gel/AFC-0.5 hydrogel. In general, the strong hydration of citrate and ammonium ions enhances the dehydration of the gelatin chains, and promotes the occurrence of hydrogen bonding between gelatin chains, leading to a red shift and broadening of the amide I band. Meanwhile, the amide II band at 1554 cm-1 moved gradually to higher wavenumbers and its intensity decreased until it disappeared with the increasing of AFC content. This may be due to the coordination of ferric ions with the amide groups on the gelatin chains. It was reported that Fe–N and Fe–O coordination bonds could be formed between 2,6-pyridine dicarboxamide and Fe3+.39 Furthermore, this metal-ligand interaction could result in a red shift of the amide I band and a blue-shift of amide II band in the diamide pyridine/Fe3+ complex.40

Noteworthy, all the composite hydrogels showed an obvious absorption peak at 1392 cm-1, attributing to the bending vibration of C-H groups and the symmetric deformation vibration of -CH3 groups.20 Additionally, the intensity of this peak gradually increases with an increase in AFC content. This result strongly suggests an enhancement of hydrophobic interactions between gelatin chains, which is induced by the dehydration of gelatin molecules due to the strong hydration of citrate and ammonium ions. Similar observations have been reported previously by other researchers for gelatin-based hydrogels with the incorporation of strongly hydrated ions.1,21,23,24

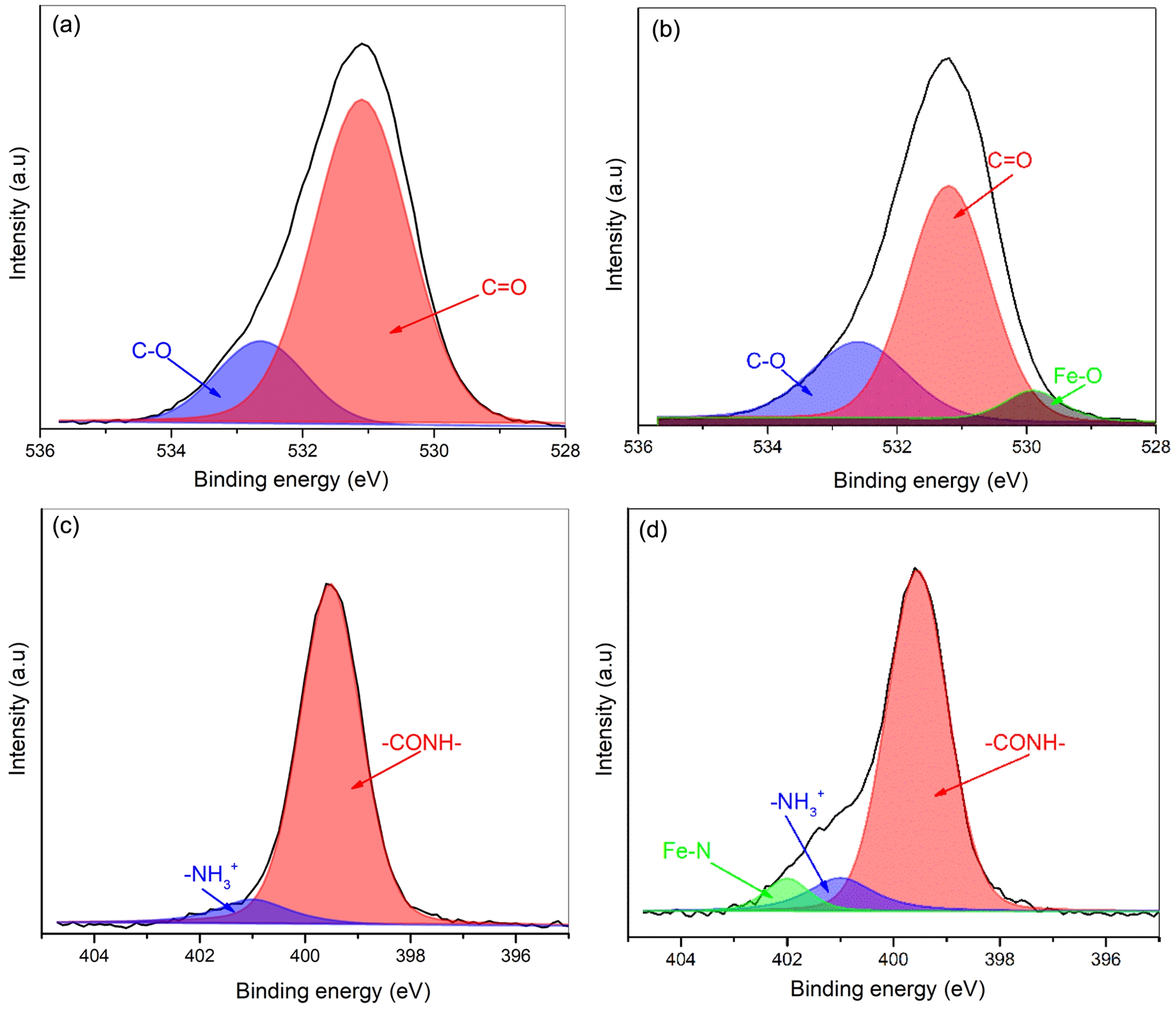

XPS Analysis. To further exploit the interaction of gelatin with AFC, XPS experiments were conducted, and the results were shown in Figure 3. In this study the 1s orbitals of the O and N elements of gelatin were mainly investigated. For pristine gelatin films (Figure 3(a)), two characteristic signals of O 1s appeared at 532.8 eV and 531.1 eV, which could be attributed to C-O and C=O, respectively.41 After the gelatin hydrogel was immersed in ammonium iron citrate solutions, a new peak at 529.9 eV appeared for composite films (Figure 3(b)), which could be assigned to the Fe-O bonds.42 This observation indicates that the ferric ions were coordinated with the oxygen of the amide groups in protein. Noteworthy, in this work the carboxyl groups on the backbone of gelatin should not be ionized due to the pH of sample solutions below the isoelectric point (IEP) of protein. Meanwhile, the amino groups of gelatin were protonated to -NH3+, which is confirmed by the characteristic peak of N 1s appeared at 401.2 eV in pristine gelatin films (Figure 3(c)). Another peak of N 1s at 399.7 eV was attributed to -CONH.43 After the gelatin hydrogel was treated with ammonium iron citrate solutions, a new signal at 402.1 eV appeared in the composite film (Figure 3(d)), which could be assigned to Fe-N bonds. These results strongly suggested that the nitrogen, as well as oxygen of the amide groups in gelatin could coordinate with ferric ions. A similar observation has previously been made by Li et.al that the Fe(III)–N and Fe(III)–O bonds were formed in Fe(III)-2,6-pyridine dicarboxamide coordination complex.39

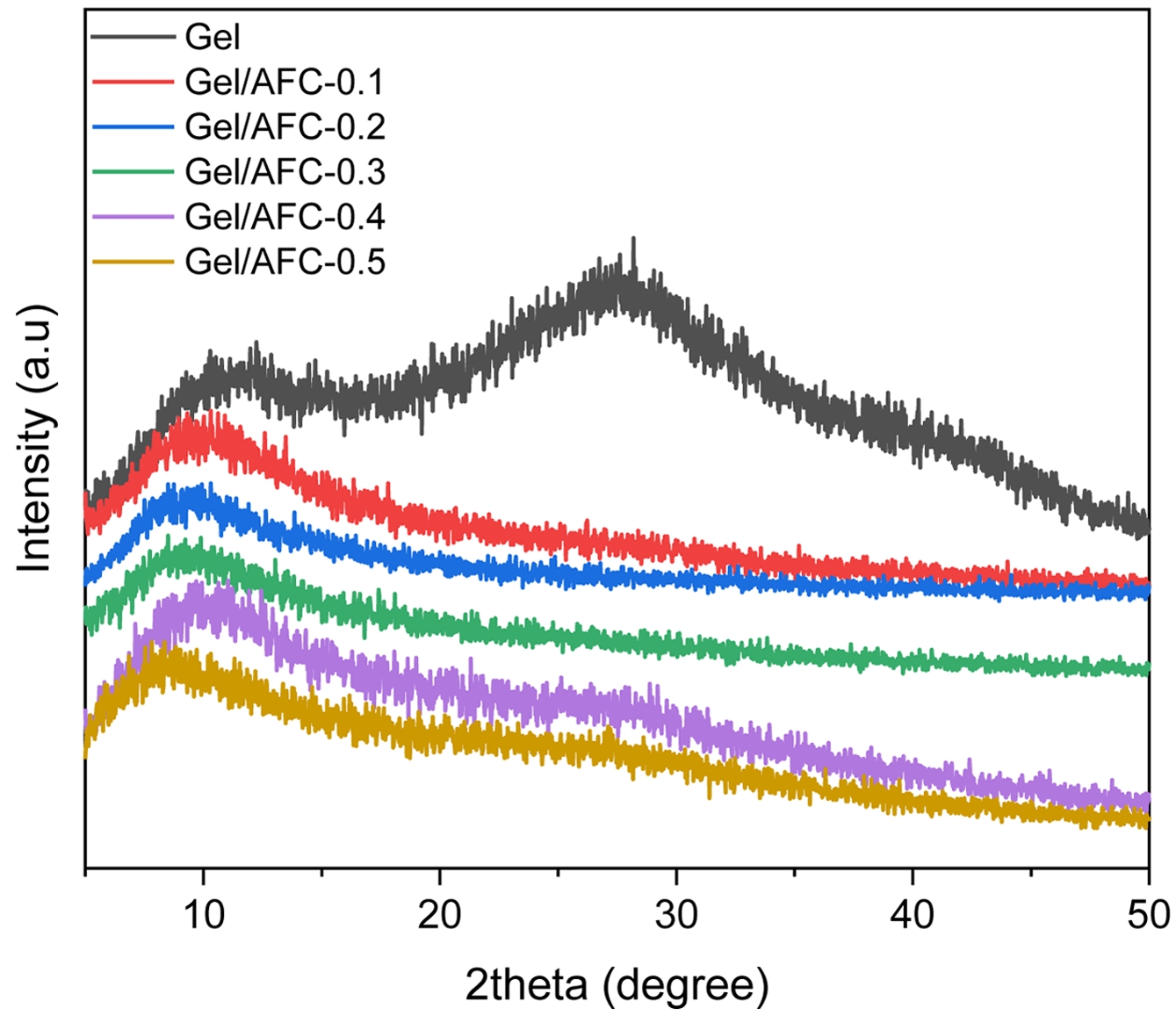

Structure of Gel/AFC-x Composite Hydrogels. To explore the influence of salt concentration on the microstructure of Gel/AFC-x composite hydrogels, a wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) experiment was conducted and the result was displayed in Figure 4. It can be observed that two broad peaks appear at 2θ = 11° and 27° for pristine gelatin hydrogels. The former can be attributed to the ordered triple helix structure, while the latter is related to the random coils of protein molecules.36 In general, the broad diffraction peak at 2θ = 11° indicates a low periodicity in the lateral stack of the triple helices in the hydrogels. This can be explained by the fact that a large number of water molecules existing in the hydrogels can penetrate into the triple helices, causing them to move away from each other and reducing the crystallinity of gelatin hydrogels.

After the hydrogels were soaked in ammonium iron citrate solutions, the broad diffraction peak at 2θ= 11° slightly narrowed and moved gradually to lower angles with increasing AFC content. For instance, this diffraction peak became sharper and moved to low angles of 2θ = 8° for the Gel/AFC-0.5 hydrogel, indicating an enhanced crystallinity of hydrogels. This may be due to the strong hydration of citrate and ammonium ions, which cause the dehydration of gelatin chains. As a result, the gelatin molecules move closer to each other and induce the formation of triple helices, resulting in an increase in the crystallinity of gelatin hydrogels. Similar results were reported for gelatin hydrogels immersed in K3Cit solutions.20

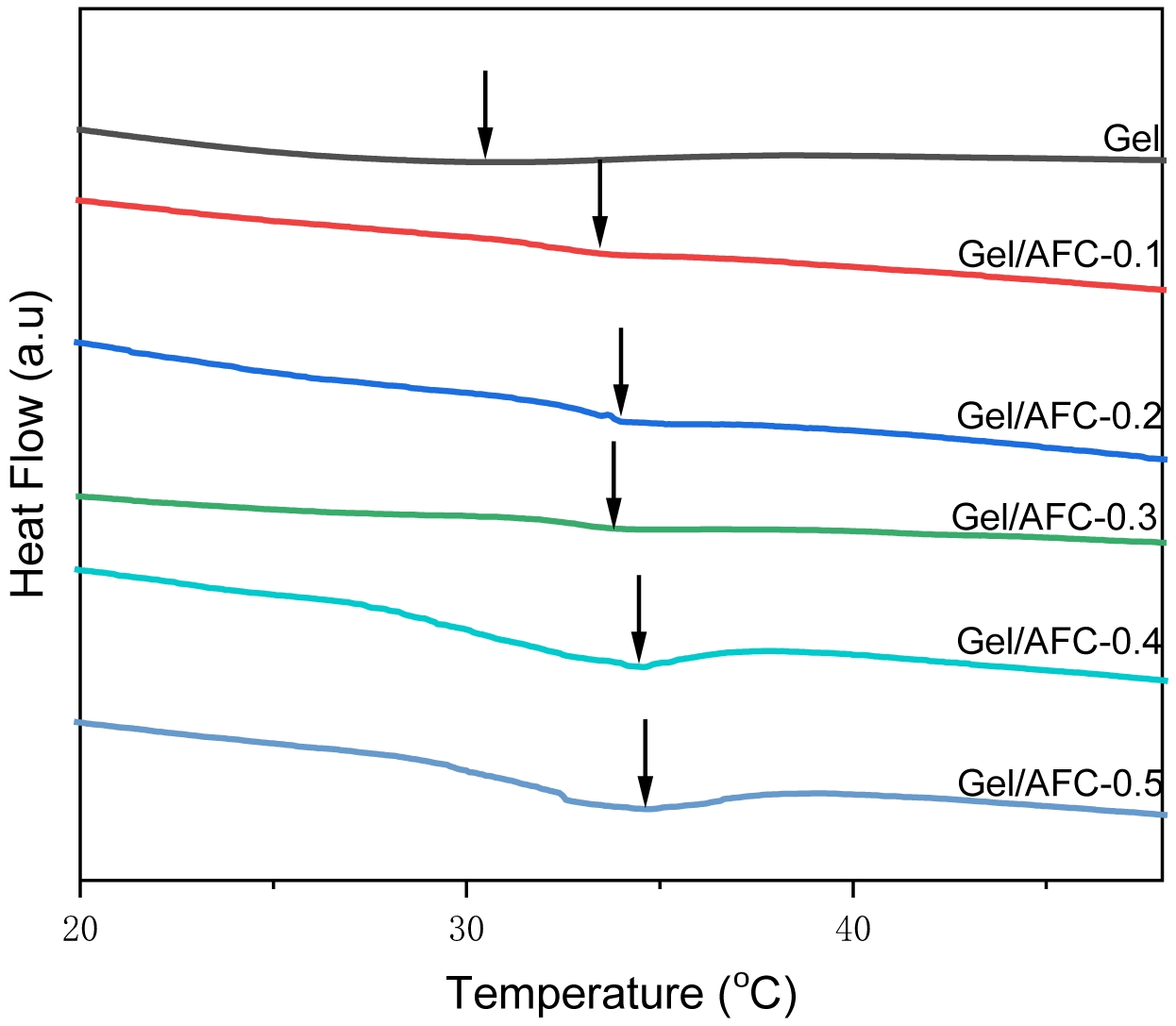

To further confirm the helix structural changes in the gelatin hydrogels immersed in ammonium iron citrate solutions, the melting behaviors of composite hydrogels were investigated with DSC (Figure 5). It can be seen that an endothermal peak appears around 30 ℃ in pristine gelatin hydrogel, which corresponds to the melting temperature (Tm) of the gelatin hydrogel. After soaking in AFC solutions, the melting transition temperature (Tm) of composite hydrogels is improved. With an increase of AFC content, the Tm is increased to 33.44, 33.98, 33.78, 34.41, and 34.65 ℃ for the Gel/AFC-0.1, Gel/AFC-0.2, Gel/AFC-0.3, Gel/AFC-0.4, and Gel/AFC-0.5, respectively. In addition, their melting enthalpies are also increased with AFC content. In general, the Tm of gelatin hydrogels depends on the length of triple helices, while their melting enthalpies are closely related to the helix content.44 This result indicates that the introduction of citrate and ammonium ions facilitates the growth of triple helices due to their strong hydration characters, and hence causes an increase of Tm of hydrogels. Meanwhile, the dehydration of gelatin molecules induces the bundling of gelatin chains and the formation of triple helices. A similar observation was reported for gelatin hydrogels soaked in K3Cit solutions.20 Noteworthy, the broadening of the melting peaks of composite hydrogels was mainly due to the length distribution of triple helices.45

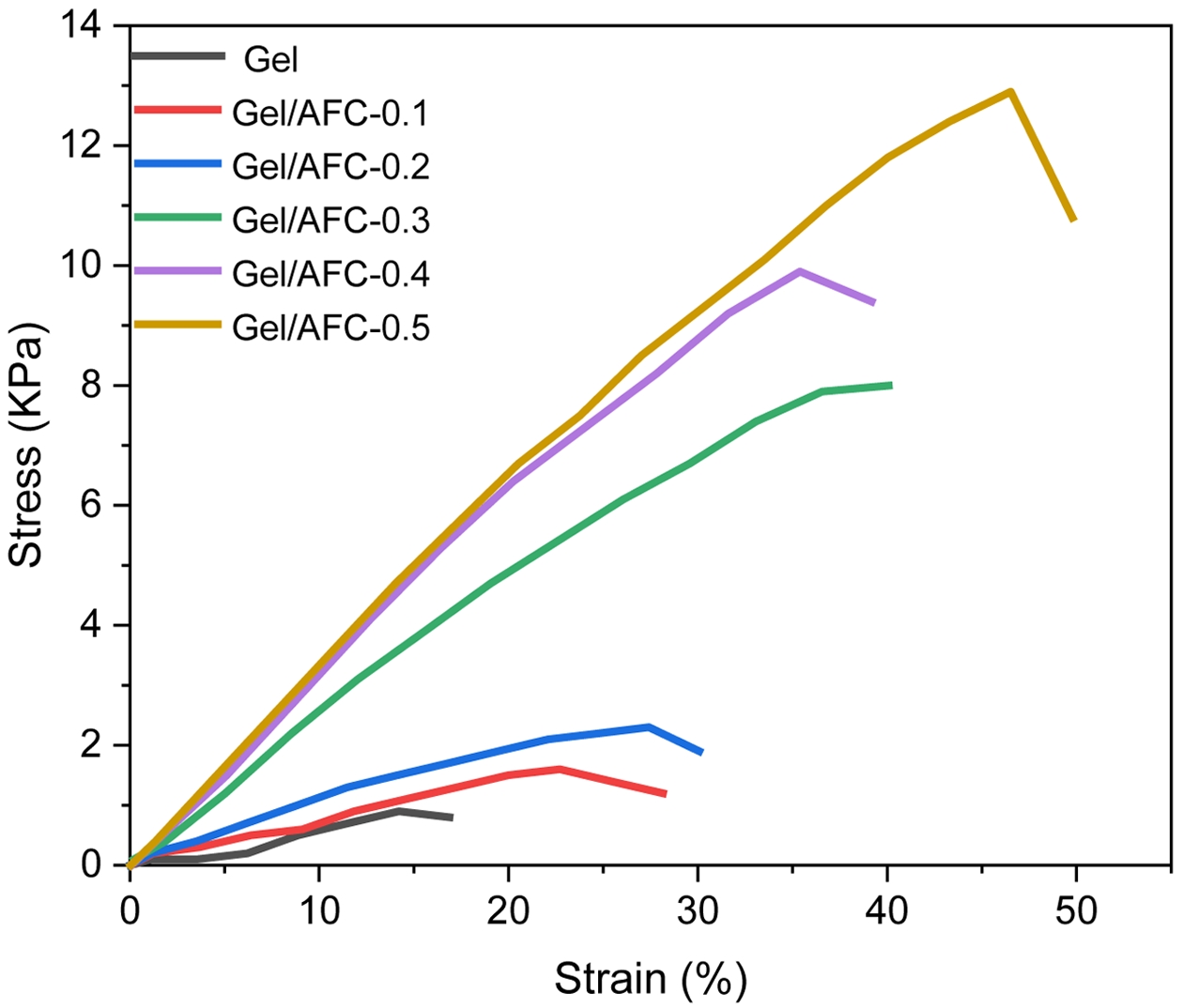

Mechanical Properties of Gel/AFC-x Composite Hydrogels. The stress-strain curves of gelatin and Gel/AFC-x composite hydrogels are shown in Figure 6, and the results are illustrated in Table 2. It is seen that the pristine gelatin hydrogel has low strength (~1 KPa) and poor toughness (~16.9%), due to the low helix content of gelatin, and these triple helices act as physical crosslinks in the gels. After the gelatin hydrogel was immersed in ammonium iron citrate solutions, the mechanical properties of the hydrogels were significantly enhanced. Furthermore, both the mechanical strength and elongation at break were simultaneously improved with an increase in AFC content. For example, the tensile strength and elongation at break are increased up to 13 KPa and 49.8%, respectively, for the Gel/AFC-0.5 composite hydrogel. Compared with pristine gelatin hydrogel, its strength and toughness are increased by approximately 12 times and twice, respectively. This significant enhancement of mechanical strength can be explained by the fact that the strong hydration effects of citrate and ammonium ions promote the formation of helix structure. The strength of gelatin hydrogels is directly related to the content of triple helices, which act as physical crosslinks in the gels. In addition, the sheer decrease in water fraction (Table 1) also contributes in the rise in tensile strength. Therefore, the strength of the hydrogels is significantly increased by soaking treatment. Similar results were reported by other researchers for gelatin hydrogels immersed in the Hofmeister series of salt solutions.1,20-23

It should be noted that the mechanical strength of Gel/AFC composite hydrogels was much lower than those of immersed gelatin hydrogels via Fe3+ or ammonium salt treatments. For instance, Wang et al. reported the compression strength of gelatin hydrogel treated with 0.5 M Fe3+ solution reached up to 65 MPa.29 In addition, the gelatin hydrogels soaked in 30 wt% (NH4)2SO4 solution possessed a high tensile strength of 4.0 MPa.1 These discrepancies in strength may be due to different gelatin concentration, salt concentration and testing mode.

In addition to triple helices, the ferric ions also function as crosslinks between the gelatin chains due to the coordination of Fe3+ with gelatin, resulting in enhanced mechanical strength of hydrogels. This interchain metal-ligand interaction has been previously investigated in relation to its influence on the mechanical properties of protein-based hydrogels.29,46 Moreover, an increase in the triple-helix content could improve the toughness of the gelatin hydrogels.47 Thus the elongation at break of composite hydrogels also increases with an increase in AFC content. In addition, both the tensile modulus and toughness increased with an increase in AFC content. These observations indicate that both the strength and toughness of hydrogels can be simultaneously enhanced by soaking treatment.

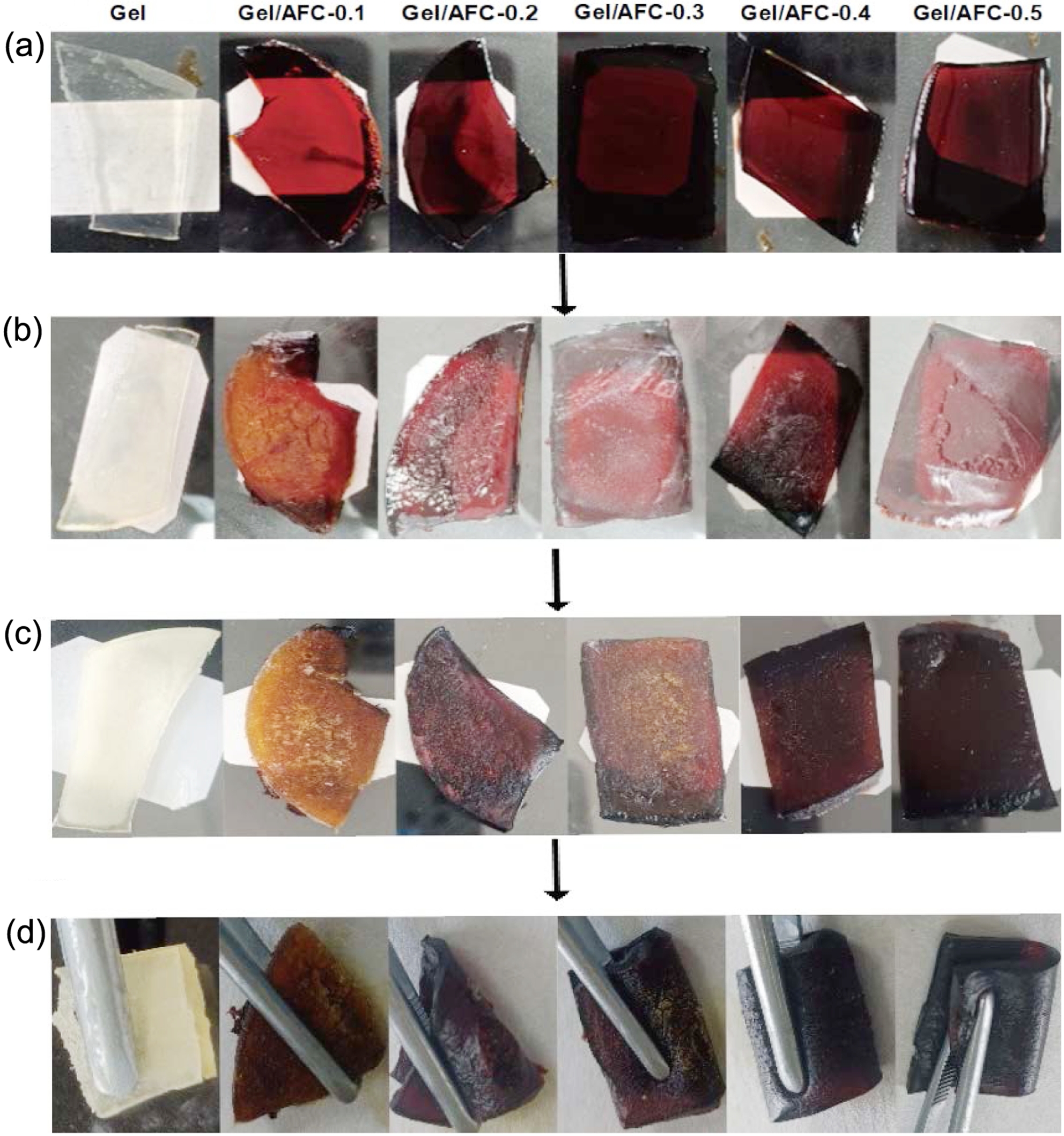

Anti-freezing Performances of Gel/AFC-x Composite Hydrogels. The freezing resistance of Gel/AFC-x composite hydrogels was studied, and the result was displayed in Figure 7. It is observed that all hydrogels are transparent and elastic at room temperature (Figure 7(a)). After being stored at -22 ℃ for 1 hour, the pristine gelatin hydrogel (Gel) could easily turn into white solid, and the frozen hydrogel became hard, brittle, and prone to be broken by bending. Additionally, the Gel/AFC-0.1 and Gel/AFC-0.2 composite hydrogels also froze with reduced transparency. However, no apparent freezing phenomenon occurred in the Gel/AFC-0.3, Gel/AFC-0.4, and Gel/AFC-0.5 composite hydrogels, which maintained good transparency (Figure 7(b)). When the hydrogels were stored at -22 ℃ for 48 hours, only the Gel/AFC-0.5 composite hydrogel did not freeze and still retained good flexibility, and other hydrogels were frozen and susceptible to bending and breaking (Figure 7(c) and 7(d)). These observations reveal that the introduction of ammonium iron citrate can enhance the freezing resistance of gelatin hydrogels.

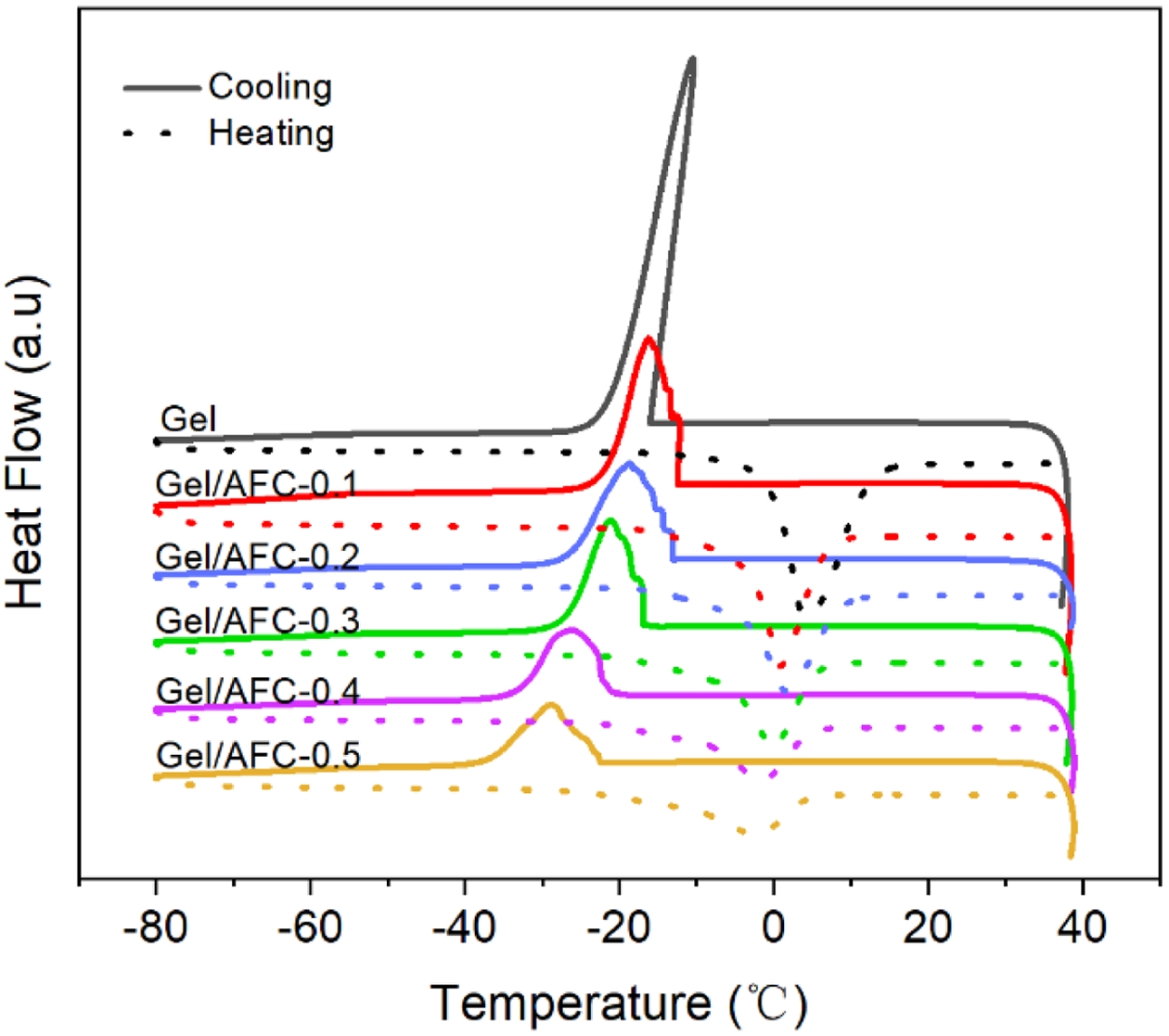

To further evaluate the anti-freezing performances of hydrogels, DSC experiments were carried out and the result was displayed in Figure 8. It is observed that a significant exothermic peak appeared at -10.52 ℃ for the pristine gelatin hydrogel, which is caused by the freezing transition of water molecules existed in the hydrogels. After soaking in AFC solutions, this exothermic peak moved to low temperatures and the freezing point decreased gradually with an increase in AFC content. For instance, the freezing temperature decreased from -16.85 ℃ for Gel/AFC-0.1 to -29.85 ℃ for Gel/AFC-0.5. This result indicates that the introduction of ammonium iron citrate endows hydrogels with good frost resistance. It can be explained by the fact that the introduction of strongly hydrated ions (citrate and ammonium ions) destroys the hydrogen bonds between water molecules. As a result, the formation of ice crystals is hampered, resulting in a decrease in the freezing point. This enhancement of frost resistance has been reported previously by Qin et al.23 for the gelatin hydrogels soaked in sodium citrate solutions. Noteworthy, the freezing-transition peak broadened and weakened with an increase in AFC content. The former was attributed to the obstruction of ice crystal formation owing to the destruction of hydrogen bonds between water molecules, while the latter is associated with a reduction of water content due to the dehydration of gelatin molecules. A similar result was observed for the gelatin-DES hydrogel system.36

|

Figure 1 The dependence of hydrogel weight on immersion time in AFC solutions at different concentrations (Mt: the weight of hydrogels at t time, M0: initial weight of hydrogels) |

|

Figure 2 FTIR spectra: (a) enlarged spectra; (b) gelatin and immersed hydrogels |

|

Figure 3 The high-resolution XPS spectra: (a) O 1s; (c) N 1s in gelatin films; (b) O 1s; (d) N 1s in Gel/AFC-0.5 films. |

|

Figure 4 WAXD Spectra of Gelatin and Immersed Hydrogels. |

|

Figure 5 DSC thermograms of gelatin and immersed hydrogels. |

|

Figure 6 Stress−strain curves of gelatin and immersed hydrogels. |

|

Figure 7 (a) The appearances of hydrogels stored at room temperature; (b) -22 ℃ for 1 h; (c) -22 ℃ for 48 h; (d) photographs of hydrogels stored at -22 ℃ for 48 h under the fold. |

|

Figure 8 DSC thermograms of gelatin and immersed hydrogels. |

Gelatin/ammonium ferric citrate (AFC) composite hydrogels were successfully fabricated using a simple soaking technique. The introduction of ammonium ion and citrate ion promoted the dehydration of gelatin chains, and the hydrogen bonding, as well as hydrophobic interactions between gelatin molecules were enhanced, leading to the formation of a helix structure. Consequently, the crystallinity of gelatin hydrogels was increased, endowing hydrogels with simultaneously enhanced strength and toughness. Furthermore, the ferric ions could crosslink gelatin chains through the coordination of Fe3+ with N and O on the amide groups in gelatin, which also contributed to the mechanical strength of hydrogels. Moreover, the thermal stability and freeze resistance of the gelatin hydrogels were significantly improved. It is noteworthy that the introduction of Fe³⁺ may create cytotoxicity concerns that cannot be overlooked.

- 1. He, Q.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Hofmeister Effect-Assisted One Step Fabrication of Ductile and Strong Gelatin Hydrogels. Adv. Func. Mater. 2018, 28, 1705069.

-

- 2. Wang, X. J.; Qiao, C. D.; Jiang, S.; Liu, L. B.; Yao, J. S. Wang, X. Hofmeister Effect in Gelatin-based Hydrogels with Shape Memory Properties. Colloid. Surface. B 2022, 217, 112674.

-

- 3. Qin, Z. H.; Dong, D. Y.; Yao, M. M.; Yu, Q. Y.; Sun, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, H. T.; Yao, F. L.; Li, J. J. Freezing-Tolerant Supramolecular Organohydrogel with High Toughness, Thermoplasticity, and Healable and Adhesive Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21184-21193.

-

- 4. Jiang, L. B.; Su, D. H.; Ding, S. L.; Zhang, Q. C.; Li, Z. F.; Chen, F. C.; Ding, W.; Zhang, S. T.; Dong, J. Salt-assisted Toughening of Protein Hydrogel with Controlled Degradation for Bone Regeneration. Adv. Func. Mater. 2019, 29, 1901314.

-

- 5. Hellio, D.; Djabourov, M.; Physically and Chemically Crosslinked Gelatin Gels. Macromol. Symp. 2006, 241, 23-27.

-

- 6. Van Den Bulcke, A. I.; Bogdanov, B.; De Rooze, N.; Schacht, E. H.; Cornelissen, M.; Berghmans, H. Structural and Rheological Properties of Methacrylamide Modified Gelatin Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2000, 1, 31-38.

-

- 7. Balakrishnan, B.; Mohanty, M.; Umashankar, P. R.; Jayakrishnan, A. Evaluation of An In Situ Forming Hydrogel Wound Dressing Based on Oxidized Alginate and Gelatin. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 6335-6342.

-

- 8. Derkach, S. R.; Voron'ko, N. G.; Kuchina, Y. A.; Kolotova, D. S.; Gordeeva, A. M.; Faizullin, D. A.; Gusev, Y. A.; Zuev, Y. F.; Makshakova, O. N. Molecular Structure and Properties of κ-carrageenan-gelatin Gels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 197, 66-74.

-

- 9. Zhang, H. J.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Han, Q.; You, X. Developing Super Tough Gelatin-based Hydrogels by Incorporating Linear Poly(methacrylic acid) to Facilitate Sacrificial Hydrogen Bonding. Soft. Matter. 2020, 16, 4723-4727.

-

- 10. Wan, C.; Frydrych, M.; Chen, B. Strong and Bioactive Gelatin-graphene Oxide Nanocomposites. Soft. Matter. 2011, 7, 6159-6166.

-

- 11. Li, H.; Wang, D. Q.; Liu, B. L.; Gao, L. Z. Synthesis of a Novel Gelatin-carbon Nanotubes Hybrid Hydrogel. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2004, 33, 85-88.

-

- 12. Gong, J. P.; Katsuyama, Y.; Kurokawa, T.; Osada, Y. Double-network Hydrogels with Extremely High Mechanical Strength. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 1155-1158.

-

- 13. Gong, J. P. Why are Double Network Hydrogels so Tough?. Soft. Matter. 2010, 6, 2583-2590.

-

- 14. Wang, Z. J.; Jiang, J. L.; Mu, Q. F.; Maeda, S.; Nakajima, T.; Gong, J. P. Azo-Crosslinked Double-Network Hydrogels Enabling Highly Efficient Mechanoradical Generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 3154-3161.

-

- 15. Samp, M. A.; Iovanac, N. C.; Nolte, A. J. Sodium Alginate Toughening of Gelatin Hydrogels. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 3, 3176-3182.

-

- 16. Ren, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Li, M.; Yang, W. Double Network Gelatin/chitosan Hydrogel Effective Removal of Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. J. Polym. Environ. 2022,30, 2007-2021.

-

- 17. Sun, J. S.; Sun, M. Y.; Zang, J. C.; Zhang, T.; Lv, C. Y.; Zhao, G. H. Highly Stretchable, Transparent, and Adhesive Double-Network Hydrogel Dressings Tailored with Fish Gelatin and Glycyrrhizic Acid for Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 42304-42316.

-

- 18. Yan, X. Q.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, L.; Chen, H.; Wei, D. D.; Chen, F.; Tang, Z. Q.; Yang, J.; Zheng, J. High Strength and Self-healable Gelatin/polyacrylamide Double Network Hydrogels. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 7683-7691.

-

- 19. Tang, L.; Zhang, D.; Gong, L.; Zhang, Y. X.; Xie, S. W.; Ren, B. Q.; Liu, Y. L.; Yang, F. Y.; Zhou, G. Y.; Chang, Y.; Tang, J. X.; Zheng, J. Double-Network Physical Cross-Linking Strategy To Promote Bulk Mechanical and Surface Adhesive Properties of Hydrogels. Macromolecules 2019,52, 9512-9525.

-

- 20. Wang, X. J.; Qiao, C. D.; Jiang, S.; Liu, L. B.; Yao, J. S. Strengthening Gelatin Hydrogels Using the Hofmeister Effect. Soft. Matter. 2021,17, 1558-1565.

-

- 21. Chen, H. R.; Shi, P. J.; Fan, F. J.; Chen, H.; Wu, C.; Xu, X. B.; Wang, Z. Y.; Du, M. Hofmeister Effect-assisted One Step Fabrication of Fish Gelatin Hydrogels. LWT 2020,121, 108973.

-

- 22. Liu, C.; Zhang, H. J.; You, X.; Cui, K.; Wang, X. Electrically Conductive Tough Gelatin Hydrogel. Adv. Electron. Mater 2020, 6, 2000040.

-

- 23. Qin, Z. H.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H. T.; Yu, Q. Y.; Wang, X. Y.; He, S. S.; Yao, F. L.; Li, J. J. A Transparent, Ultrastretchable and Fully Recyclable Gelatin Organohydrogel Based Electronic Sensor with Broad Operating Temperature. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020,8, 4447-4456.

-

- 24. Sun, X.; Yao, F. L.; Wang, C. Y.; Qin, Z. H.; Zhang, H. T.; Yu, Q. Y.; Zhang, H.; Dong, X. R.; Wei, Y. P.; Li, J. J. Ionically Conductive Hydrogel with Fast Self-Recovery and Low Residual Strain as Strain and Pressure Sensors. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2020, 41, 2000185.

-

- 25. Chen, F.; Yang, K. X.; Zhao, D. L.; Yang, H. Y. Thermal- and Salt-activated Shape Memory Hydrogels Based on a Gelatin/polyacrylamide Double Network. RSC. Adv. 2019, 9, 18619-18626.

-

- 26. Jaspers, M.; Rowan, A. E.; Kouwer, P. H. J. Tuning Hydrogel Mechanics Using the Hofmeister Effect. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015,25, 6503-6510.

-

- 27. Yu, D. S.; Yi, J.; Zhu S. H.; Tang, Y. H.; Huang, Y. Y.; Lin, D.; Lin, Y. H.; Hofmeister Effect-Assisted Facile One-Pot Fabrication of Double Network Organohydrogels with Exceptional Multi-Functions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2307566.

-

- 28. Luo, B.; Cai, C. C.; Liu, T.; Meng X. J.; Zhuang, X. L.; Liu, Y. H.; Gao, C.; Chi, M. C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. L.; Bai, Y. Y.; Wang, S. F.; Nie. S. X. Multiscale Structural Nanocellulosic Triboelectric Aerogels Induced by Hofmeister Effect. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023,33, 2306810.

-

- 29. Wang, J. R.; Fan, X. L.; Liu, H.; Tang, K. Y. Self-assembly and Metal Ions-assisted One Step Fabrication of Recoverable Gelatin Hydrogel with High Mechanical Strength. Polym-Plast. Tech. Mat. 2020, 59, 1899-1909.

-

- 30. Lin, J. H.; Du, X. S. Self-healable and Redox Active Hydrogel Obtained via Incorporation of Ferric Ion for Supercapacitor Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137244.

-

- 31. Zheng, S. Y.; Ding, H.; Qian, J.; Yin, J.; Wu, Z. L.; Song, Y. H.; Zheng, Q. Metal Coordination Complexes Mediated Physical Hydrogels with High Toughness, Stick–slip Tearing Behavior, and Good Processability. Macromolecules 2016,49, 9637-9646.

-

- 32. Zhang, H. M.; Xue, K.; Shao, C. Y.; Hao, S. W.; Yang, J. Recent Progress in Bioinspired Design Strategies for Freeze Resistant Hydrogel Platforms toward Flexible Electronics. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 10316-10347.

-

- 33. Morelle, X. P.; Illeperuma, W. R.; Tian, K.; Bai, R. B.; Suo, Z. G.; Vlassak, J. J. Highly Stretchable and Tough Hydrogels below Water Freezing Temperature. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1801541.

-

- 34. Chen, H.; Ren, X.; Gao, G. Skin-inspired Gels with Toughness, Antifreezing, Conductivity, and Remoldability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 28336-28344.

-

- 35. Sang, M.; Wang, J. J.; Zuo, D. Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H. W.; Li, H. J.; Eutectogel with (NH4)2SO4-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent for Ammonium-Ion Supercapacitors. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 2455-2464.

-

- 36. Liu, R. P.; Qiao, C. D.; Liu, Q. Z.; Liu, L. B.; Yao, J. S. Fabrication and Properties of Anti-freezing Gelatin Hydrogels Based on a Deep Eutectic Solvent. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023,5, 4546-4553.

-

- 37. Chen, F.; Zhou, D.; Wang, J. H.; Li, T. Z.; Zhou, X. H.; Gan, T. S.; Handschuh-Wang, S.; Zhou, X. C. Rational Fabrication of Anti-Freezing, Non-Drying Tough Organohydrogels by One-Pot Solvent Displacement. Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 6678-6681.

-

- 38. Hashim, D. M.; Che Man, Y. C.; Norakasha, R.; Shuhaimi, M.; Salmah, Y.; Syahariza, Z. A. Potential use of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy for Differentiation of Bovine and Porcine Gelatins. Food. Chem. 2010,118, 856-860.

-

- 39. Li, C. H.; Wang, C.; Keplinger, C.; Zuo, J. L.; Jin, L. H.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, P.; Cao, Y.; Lissel, F.; Linder, C.; You, X. Z.; Bao, Z. N. A Highly Stretchable Autonomous Self-healing Elastomer. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 618-624.

-

- 40. Wang, Z. H.; Xie, C.; Yu, C. J.; Fei, G. X.; Wang, Z. H.; Xia, H. S. A Facile Strategy for Self-Healing Polyurethanes Containing Multiple Metal-Ligand Bonds. Macromol. Rapid. Commun. 2018,39, 1700678.

-

- 41. Yu, P.; Li, Y. Y.; Sun, H.; Ke, X.; Xing, J. Q.; Zhao, Y. R.; Xu, X. Y.; Qin, M.; Xie, J.; Li, J. S. Cartilage-Inspired Hydrogel with Mechanical Adaptability, Controllable Lubrication, and Inflammation Regulation Abilities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022,14, 27360-27370.

-

- 42. Tan, Q. W.; Li, P.; Han, K.; Liu, Z. W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; He, D. L.; An, F. Q.; Qin, M. L.; Qu, X. H. Chemically Bubbled Hollow FexO Nanospheres Anchored on 3D N-doped Few-layer Graphene Architecture as a Performance-enhanced Anode Material For Potassium-ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 744-754.

-

- 43. Xue, Y. R.; Liu, C.; Ma, Z. Y.; Zhu, C. Y.; Wu, J.; Liang, H. Q.; Yang, H. C.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Z. K. Harmonic Amide Bond Density as a Gamechanger for Deciphering the Crosslinking Puzzle of Polyamide. Nat. Commun. 2024,15, 1539.

-

- 44. Gornall, J. L.; Terentjev, E. M. Helix-coil Transition of Gelatin: Helical Morphologyand Stability. Soft. Matter. 2008, 4, 544-549.

-

- 45. Pezron, I.; Djabourov, M.; Bosio, L.; Leblond, J. X-ray Diffraction of Gelatin Fibers in the Dry and Swollen States. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 1990, 28, 1823-1839.

-

- 46. Ovando-Roblero, A.; Meza-Gordillo, R.; Castañeda-Valbuena, D.; Castañó-González, J. H.; Ruiz-Valdiviezo, V. M.; Gutiérrez-Santiago, R.; Grajales-Lagunes, A. Metal-chelated Biomaterial From Collagen Extracted From Pleco Skin (Pterygoplichthys pardalis). SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 321.

-

- 47. Bigi, A.; Panzavolta, S.; Rubini, K. Relationship Between Triple-helix Content and Mechanical Properties of Gelatin Films. Biomaterials 2004,25, 5675-5680.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2026; 50(1): 49-59

Published online Jan 25, 2026

- 10.7317/pk.2026.50.1.49

- Received on Jun 10, 2025

- Revised on Sep 15, 2025

- Accepted on Oct 14, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Congde Qiao, Wenke Yang

-

School of Materials Science and Engineering, Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy of Sciences), Jinan 250353, PR China

- E-mail: cdqiao@qlu.edu.cn, yangwen_ke@126.com

- ORCID:

0000-0002-7969-4206, 0000-0001-9323-9982

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.