- Characterization and Washing of End-of-Life Vehicle-Derived Polyamide 6 Composites for Recycling Applications

Department of Polymer Engineering, Pukyong National University, 45 Yongso-ro, Nam-gu, Busan 48513, Korea

- 폐차 유래 폴리아미드 6 복합재의 재활용을 위한 특성 분석 및 세정

국립 부경대학교 고분자공학전공

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

As recycling plays a crucial role in environmental sustainability, we investigated the properties of polyamide (PA) 6 composites derived from end-of-life vehicles (ELV) and evaluated the effects of various cleaning agents and conditions. The primary objective of this work is to evaluate washing conditions that can effectively remove organic contaminants that adhere to ELV-derived PA6 composites during vehicle use. Prior to washing, the chemical composition and surface contaminants of the recycled ELV PA 6 composites were characterized using a range of analytical techniques. Following the cleaning process, total organic carbon (TOC) content was measured, and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) was also employed to assess the removal efficiency of volatile organic compounds under different cleaning conditions. The results indicate that cleaning with dishwasher detergent at 70°C under sonication is the most effective method. Furthermore, GC–MS analysis revealed a significant reduction in the concentrations of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) after washing. These findings suggest that appropriate cleaning treatments enhance material purity and contribute to improved recycling efficiency.

본 연구에서는 폐차(end-of-life vehicle, ELV)로부터 회수된 폴리아미드(PA) 6 복합재의 특성을 조사하고, 다양한 세정제와 조건의 영향을 평가하였다. 세정 전, 재활용 ELV PA 6 복합재의 화학 조성과 표면 오염물을 분석하였으며, 세정 후에는 총유기탄소(TOC) 함량 측정 및 기체 크로마토그래피–질량분석법(GC–MS)을 이용하여 세정 조건별 휘발성유기화합물(VOC) 제거 효율을 평가하였다. 그 결과, 70 °C에서 초음파 세정과 함께 식기세척기용 세제를 사용하는 방법이 가장 효과적인 것으로 나타났다. 또한, GC–MS 분석 결과 세정 후 휘발성유기화합물의 농도가 크게 감소하였다. 이러한 결과는 적절한 세정 처리가 재질의 순도를 향상시키고 재활용 효율 개선에 기여함을 시사한다.

Analysis of end-of-life vehicles (ELV)-derived polyamide (PA) 6 composites after washing under various conditions revealed that ultrasonic cleaning with dishwasher detergent at 70 ¡ÆC achieved the highest removal efficiency, significantly reducing organic content and improving material purity.

Keywords: end-of-life vehicles, recycling, polyamide 6, washing.

This work was supported by Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE) (No. RS-2024-00421052).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Plastics offer several advantages that make them essential components in modern automobile manufacturing, meeting the evolving demands of the automotive industry.1,2

First, plastics possess an excellent strength-to-weight ratio, enabling significant vehicle weight reduction, which in turn enhances fuel efficiency and reduces greenhouse gas emissions.3,4

Second, plastics provide high design flexibility, facilitating the production of complex and customized shapes while lowering manufacturing complexity and associated costs. Third, the use of recycled plastics contributes to environmental sustainability due to their applicability in various automotive components, including both interior and engine compartment parts.5

Automotive plastics are widely used in components such as bumpers, dashboards, door panels, seats, battery housings, and engine compartments. They include polypropylene, polycarbonate, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, polyamide (PA), polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride, etc. In particular, PA is a semi-crystalline engineering thermoplastic widely used in the automotive, where it is subjected to mechanical stress and high temperatures.6 PA is widely used in airbags, engine protectors, bodywork and internal components, fasteners (bolts, bushes, threads) and in the manufacture of high performance components, helping to reduce vehicle weight and consequently decrease fuel consumption.7 The automotive sector accounts for 35% of PA consumption. Approximately 1.6 million cars are scrapped each year, and each of these end-of-life vehicles (ELV) contains approximately 175 kg of various plastic resins. Recycling rates for the plastics used in ELVs are low because there are few end markets for these materials.8

Recent studies have identified mechanical recycling as the most economically, environmentally, and technologically viable method for automotive plastic recovery.9-12

Effective decontamination is an important step in the plastic recycling process, ensuring both material quality and process efficiency. In this study, we investigated the washing processes for recycled PA6 composites from ELV. As a first step, the degree of contamination of as-received ELV-derived PA6 composites were studied. Subsequently, the ELV-derived PA6 composites were washed with different washing agents under diverse environments. To evaluate the cleaning efficiency, total organic carbon (TOC) measurements were conducted, and the results indicated that cleaning with dishwasher detergents (DD) made the most effective and reasonable result. Also, gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is used to detect the presence of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). It was found that cleaning with the dishwasher through bath sonication at 70 ℃ was most effective. The GC-MS also revealed that the such cleaning also significantly reduced the emissions of VOCs.

Materials. The shredded ELV-derived PA6 composites were supplied from Dowon Chemical. The shredded PA6 composites originated from the cylinder blocks of engines and contaminated with various lubricants and oil residues. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH; >99.0% purity) was purchased from Duksan Pure Chemical Co., Ltd. Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB; >98.0% purity) were supplied by Han Lab Co., Ltd. DD were purchased from Frosch Co., Ltd. Multi-purpose detergent (MD) was purchased from Pigeon Co., Ltd.

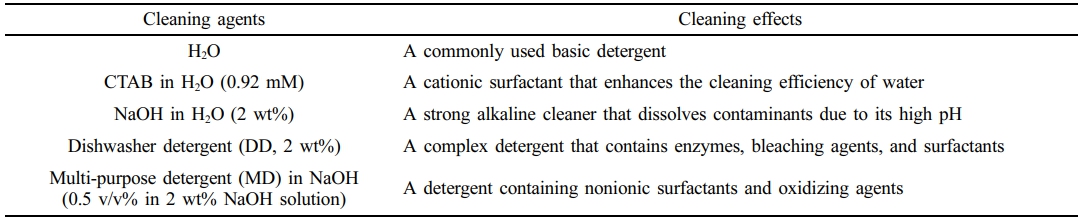

Washing Procedures. A shredded PA6 composite of 3.00 ± 0.10 g was placed in a 250 mL beaker, and 100 mL of a cleaning agents (Table 1) preheated to 25 or 70 ℃ was added and washed through either overhead stirring or bath sonication. The speed of the overhead stirrer was around 200 rpm while the bath sonication was conducted under 40 kHz. The washing was conducted at two different temperatures: 25 and 70 ℃. 25 ℃was selected as the low-energy baseline cleaning condition at room temperature, while 70 ℃ was chosen as the high-temperature condition commonly used in aqueous cleaning processes to enhance cleaning power. In aqueous and commercial detergent systems, 70 ℃ is near the upper limit of the practical temperature range and is commonly used for high temperature washing. Increasing the temperature decreases the viscosity and surface tension of the washing solution and oil/lubricant residues, which reduces the adhesion of hydrophobic contaminants to surfaces. This facilitates emulsification and dispersion by surfactants, as well as accelerating diffusion and mass transfer at the solid–liquid interface. For these reasons, 70 ℃ is a practical high-temperature washing condition that maximizes the benefit of temperature-enhanced detergency without causing thermal damage to the PA6 matrix.

The cleaning agents used in this work include distilled water, CTAB in a water solution, NaOH in water solution, DD in water solution (2 wt%), and MD in NaOH. The specific concentrations and information of each agent are summarized at Table 1. After the 30 min of washing step, the cleaning agents were collected and used for TOC analysis. The residual plastics were rinsed twice with 100 mL distilled water at 25 ℃ to eliminate the remaining chemicals. The rinsed plastics were then dried at room temperature for 48 hours and used for GC-MS.13

Characterizations. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) (TESCAN/MIRA3 LMH) was utilized to investigate the surfaces of the ELV-derived PA6 composites. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (JASCO/FT-4100) was used to evaluate the ELV-derived PA6 composites over a range of wave number from 500 to 4000 cm-1. The thermal stability of the samples was investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (TA Instruments / Discovery TGA 55. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) (Rigaku/ZSX-PrimusIV) and was used to characterize the PA6 composites.

The variation of the amount of TOC in the cleaning agents was analyzed (Shimadzu/TOC-L). The TOC content of the cleaning agents was measured before and after the washing process. An increase in TOC after washing indicates the transfer of organic oil residues from the composite surface into the cleaning agent. Therefore, a significant increase in TOC reflects a higher cleaning efficiency of the corresponding agent.

GC–MS equipped with an automatic thermal desorber (PerkinElmer, ATD650) was used to evaluate the presence and removal efficiency of surface VOCs. The headspace solid phase microextraction experiments were conducted using a vial with a volume of 240 mL, and each sample weighed approximately 5 g. The equilibration process was carried out at 120 ℃ for 60 minutes. After equilibration, the extraction was performed at room temperature for 5 minutes. GC–MS analysis was conducted under a nitrogen carrier gas flow rate of 1 mL/min, and the injection volume was set to 1 µL. The mass spectrometer was operated in full scan mode, covering a mass-to-charge range from 50 to 650.14,15

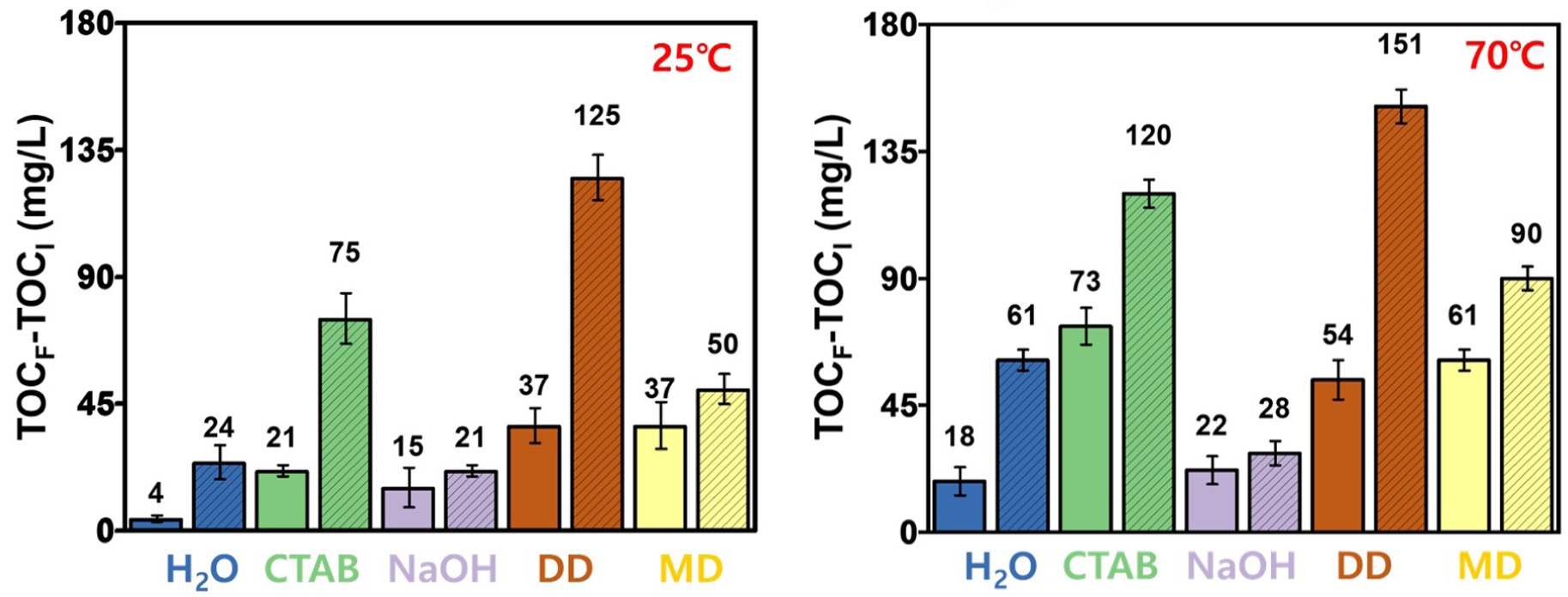

Material Characterizations. The FTIR spectra of the ELV-derived PA6 composites before and after washing are shown in Figure 1(a). Several characteristic peaks of PA6 were observed, including the amide I band at 1540 cm-1 and the amide II/CH₂ asymmetric stretching at 1635 cm-1. A broad absorption band around 3300–3400 cm-1 corresponds to N–H stretching vibrations, and peaks between 2800–3000 cm-1 are assigned to C–H stretching modes. Additional peaks at 689 cm-1 and 575 cm-1 are attributed to C–C deformation and O=C–N bending, respectively, while the region around 1000–1100 cm-1 corresponds to Si–O–Si and Si–OH stretching, indicating the presence of silicon dioxide (SiO₂) derived from glass fibers. Notably, when comparing the spectra before and after washing, peaks in the 2800–3000 cm-1 region (C–H stretch) and around 1100 cm-1 (C–O stretch)—highlighted in blue in the figure—showed a decrease in intensity, which can be attributed to the removal of oil-based contaminants and hydrocarbon residues from the surface of the composites. In contrast, peaks in the red-highlighted regions, such as the N–H stretching band at 3300 cm-1 and the C=O stretching band near 1600 cm-1, increased in intensity after washing. This indicates that the elimination of surface oil layers allowed the intrinsic molecular vibrations of the PA6 matrix to become more detectable. These spectral changes clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of the washing process in removing hydrocarbon contaminants and revealing the underlying PA6 structure.

The XRF spectrum in Figure 1(b) revealed the presence of several inorganic elements originating from fillers and additives. The dominant elements were calcium (Ca) and silicon (Si), where Ca may be derived from calcium carbonate or calcium oxide as a filler or as part of the glass fiber formulation, while Si corresponds primarily to silicon dioxide from the glass fiber. Additional elements such as bromine (Br), aluminum (Al), and sulfur were also detected. The presence of Br is likely associated with brominated flame retardants, and Al may originate from aluminum oxide, commonly used in glass fiber. Sulfur is likely introduced via sulfur-containing heat stabilizers or antioxidants. Importantly, no hazardous heavy metals were detected in the sample.

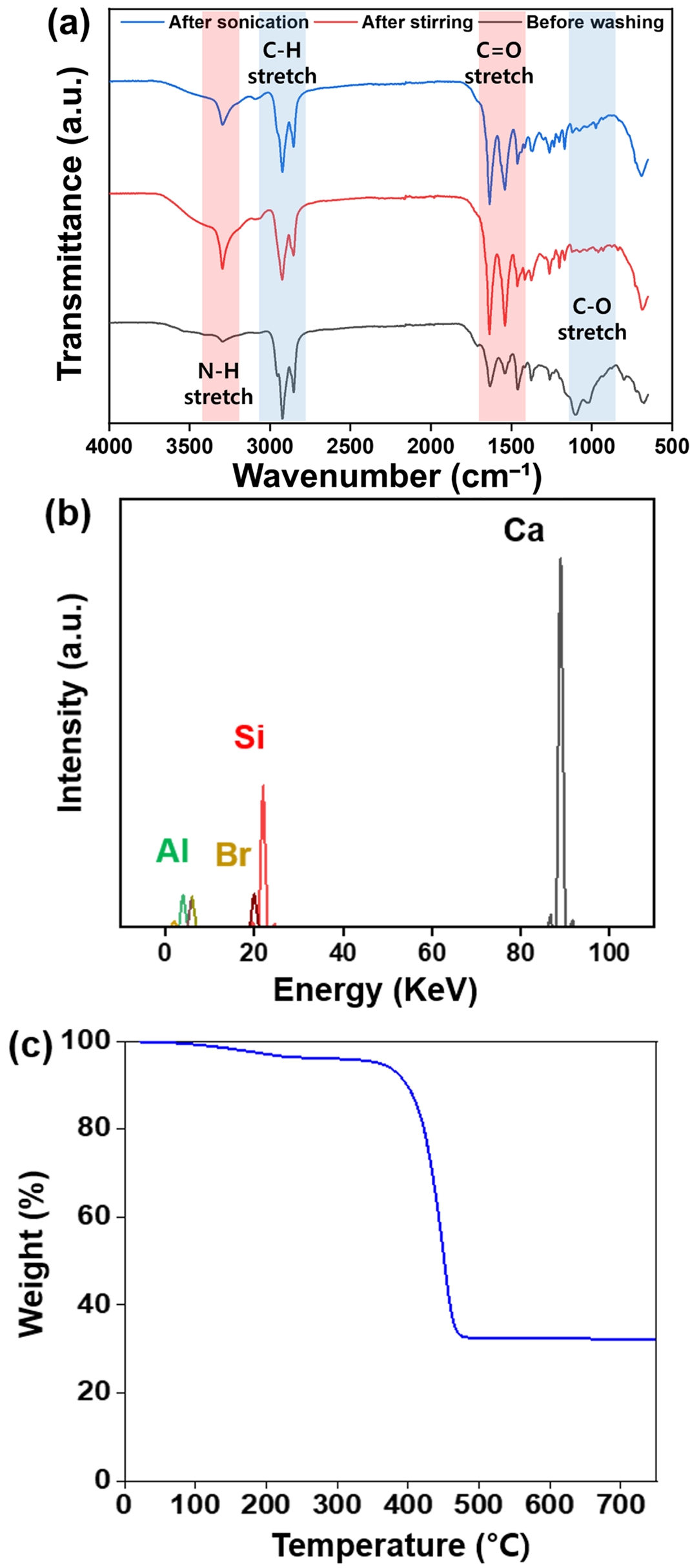

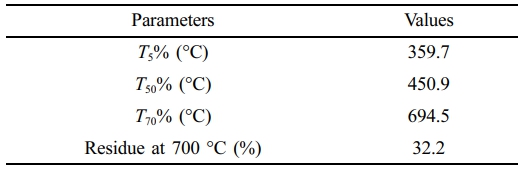

The TGA results in Figure 1(c) showed a residual weight of approximately 32.2% at 700 ℃, indicating the proportion of inorganic fillers in the composite. Relevant thermal parameters derived from the TGA curve are summarized in Table 2. In addition, SEM images of the ELV-derived PA6 composite in Figure 2 confirmed that the glass fibers were uniformly dispersed throughout the polymer matrix. The fracture surface and surface morphology revealed well-integrated fiber–matrix interfacial structures and effective embedding of glass fibers within the PA6 phase.

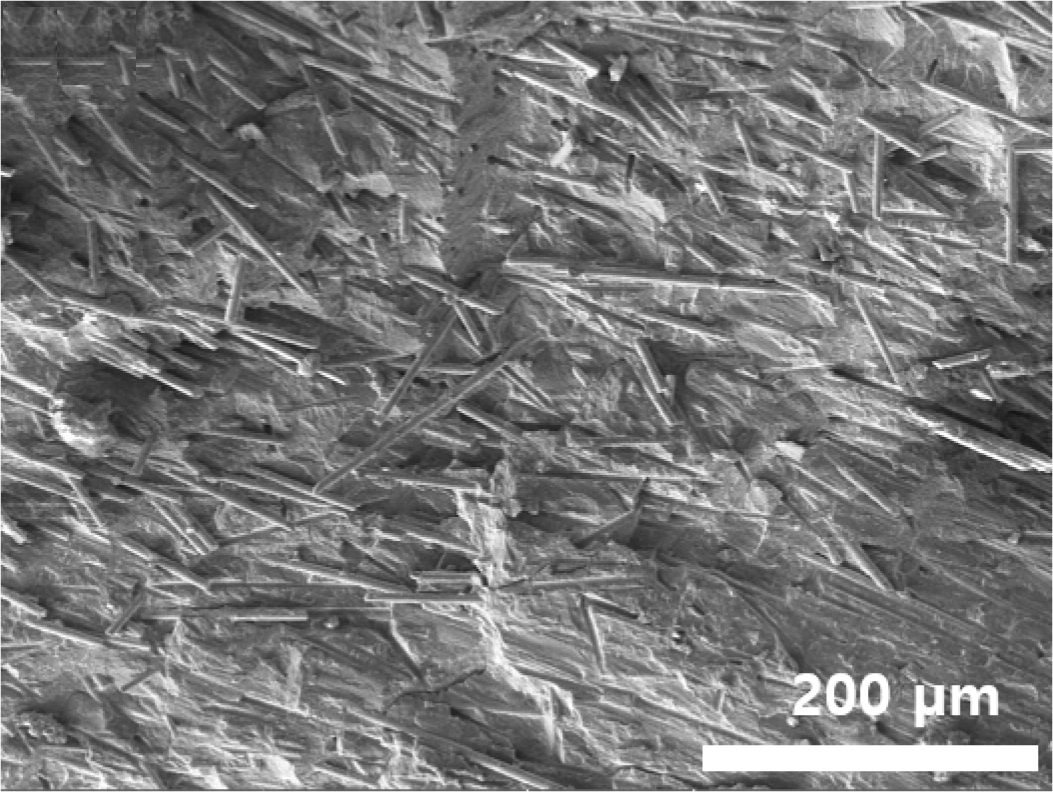

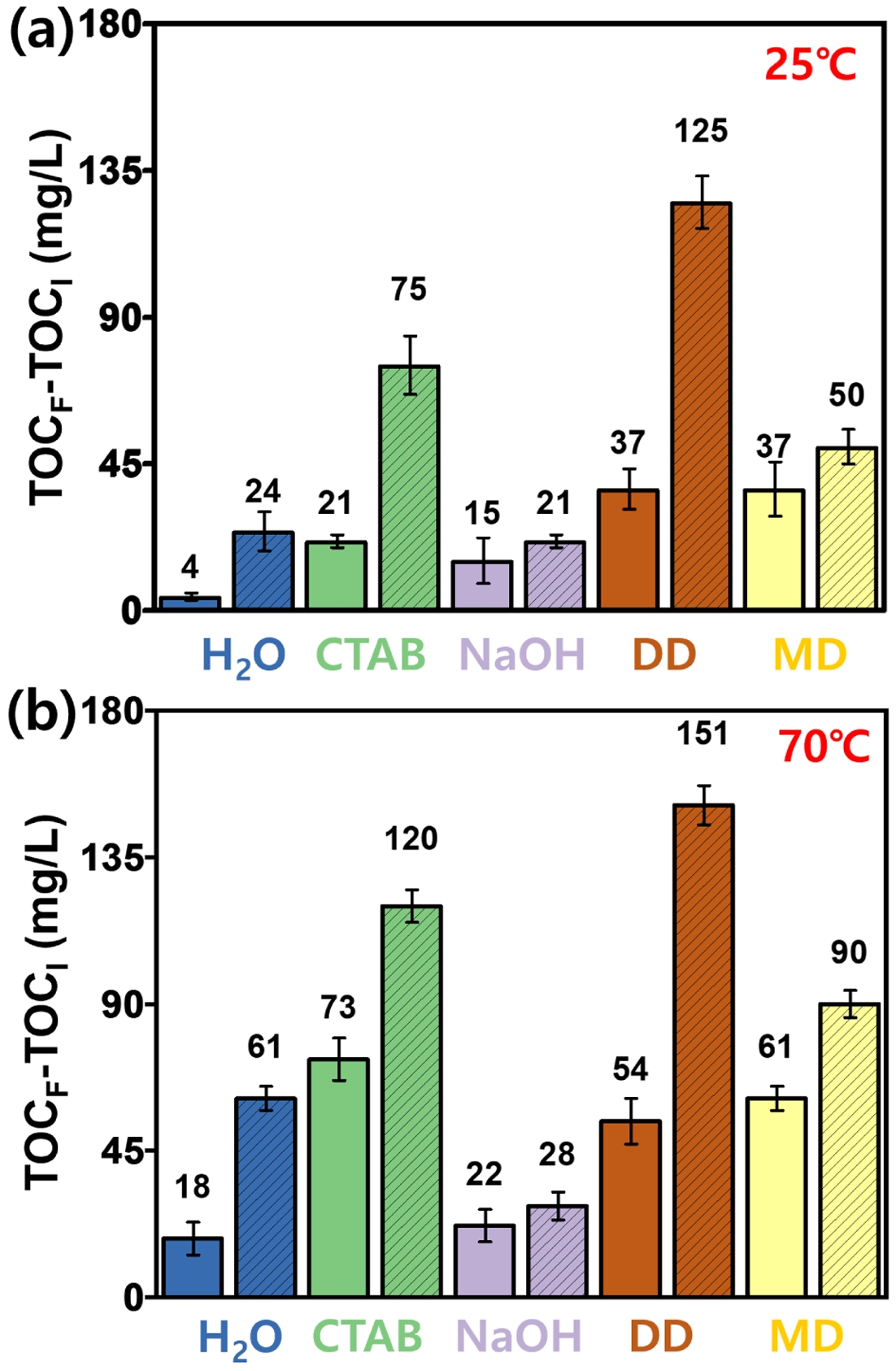

TOC. All washing experiments and TOC analyses were performed at least five times under identical conditions. The results of the TOC-based cleaning efficiency under different conditions are presented in Figure 3. At 25 ℃, cleaning with bath sonication was generally more effective than overhead stirring. Among the five tested cleaning agents, the DD dissolved in NaOH solution exhibited the highest TOC increase, followed by CTAB. For instance, under bath sonication, TOC increased by 125 mg/L with DD and by 75 mg/L with CTAB, indicating strong removal of organic contaminants. The performance of both agents was notably enhanced under sonication conditions.

When the washing temperature was raised to 70 ℃, the cleaning efficiency of all agents improved, with DD and CTAB maintaining their superior performance.16 Across both temperature conditions (25 ℃ and 70 ℃), the bath sonication consistently outperformed overhead stirring. This can be attributed to acoustic cavitation, which produces intense physical agitation, including microstreaming and shock waves. These effects facilitate mechanical detachment, enhanced dissolution, and surface activation, leading to the efficient removal of fine particles, adhered residues, and oil contaminants. Moreover, sonication allows access to micropores and irregular surface features, which are less reachable by mechanical stirring.

This study included DD as a relevant washing agent because ELV-derived PA6 composites are primarily contaminated by oil- and lubricant-based residues. These residues are similar to the greasy oils that dishwasher detergents are designed to remove. The excellent cleaning efficiency of the DD can be attributed to its complex multi-component formulation. DD typically contains a mixture of nonionic and anionic surfactants, builders, dispersants, and sometimes enzymes. The surfactants contribute to emulsification of hydrophobic contaminants, while builders—such as phosphates or citrates—soften the water by chelating calcium and magnesium ions, thereby enhancing surfactant performance. Dispersants prevent re-deposition by stabilizing detached particles in the solution. This cleaning mechanism is not unique to the DD used in this study and similar behavior would be expected with other multi-component detergents with comparable compositions. However, in this study, DD was selected as a representative example of a multi-component alkaline detergent, considering that the primary contaminants on ELV-derived PA6 composites are oil-based residues such as engine oil and lubricants.

Although enzymes primarily target food-based residues, their presence may assist in breaking down some organic components. The combined action of these ingredients leads to synergistic effects, whereby surfactants reduce interfacial tension, builders optimize the chemical environment, and dispersants ensure long-lasting cleaning stability. As a result, DD demonstrated a cleaning performance comparable to, or even exceeding, that of single-component surfactants like CTAB under certain conditions.17

In addition to DD, the superior cleaning performance of CTAB can be attributed to several mechanisms working in concert. At concentrations at or above its critical micelle concentration, CTAB forms micelles with hydrophobic cores capable of encapsulating oil molecules, allowing these contaminants to be stably dispersed in the aqueous phase.18

Additionally, CTAB significantly reduces the interfacial tension between oil and water, which promotes the breakup of large oil droplets into finer emulsified particles and thus enhances the cleaning efficiency.19

Furthermore, as a cationic surfactant, CTAB possesses a positive charge and can electrostatically interact with negatively charged oil particles, which helps to stabilize them in suspension and prevent re-deposition onto the surface.20

In contrast, NaOH alone showed relatively low cleaning performance. This is because engine oils and lubricants are highly hydrophobic and non-polar, whereas NaOH is a polar compound with limited ability to solubilize or emulsify such substances. Moreover, NaOH lacks surfactant properties and does not significantly reduce interfacial tension or promote oil dispersion. Although effective in removing polar contaminants such as proteins or organic acids, its overall cleaning efficiency is limited by poor solubility for hydrophobic residues and the absence of mechanical release mechanisms.

However, the combination of NaOH with multi-purpose detergents containing surfactants resulted in a synergistic improvement in cleaning performance. For example, at 25 ℃, the TOC increase using NaOH alone was 15 mg/L, which rose to 37 with mechanical stirring when used in combination with a multi-purpose detergent. At 70 ℃, the TOC further increased from 22 to 61 mg/L under the same combinations, clearly demonstrating the enhanced effect of temperature and surfactant-assisted formulations.21,22

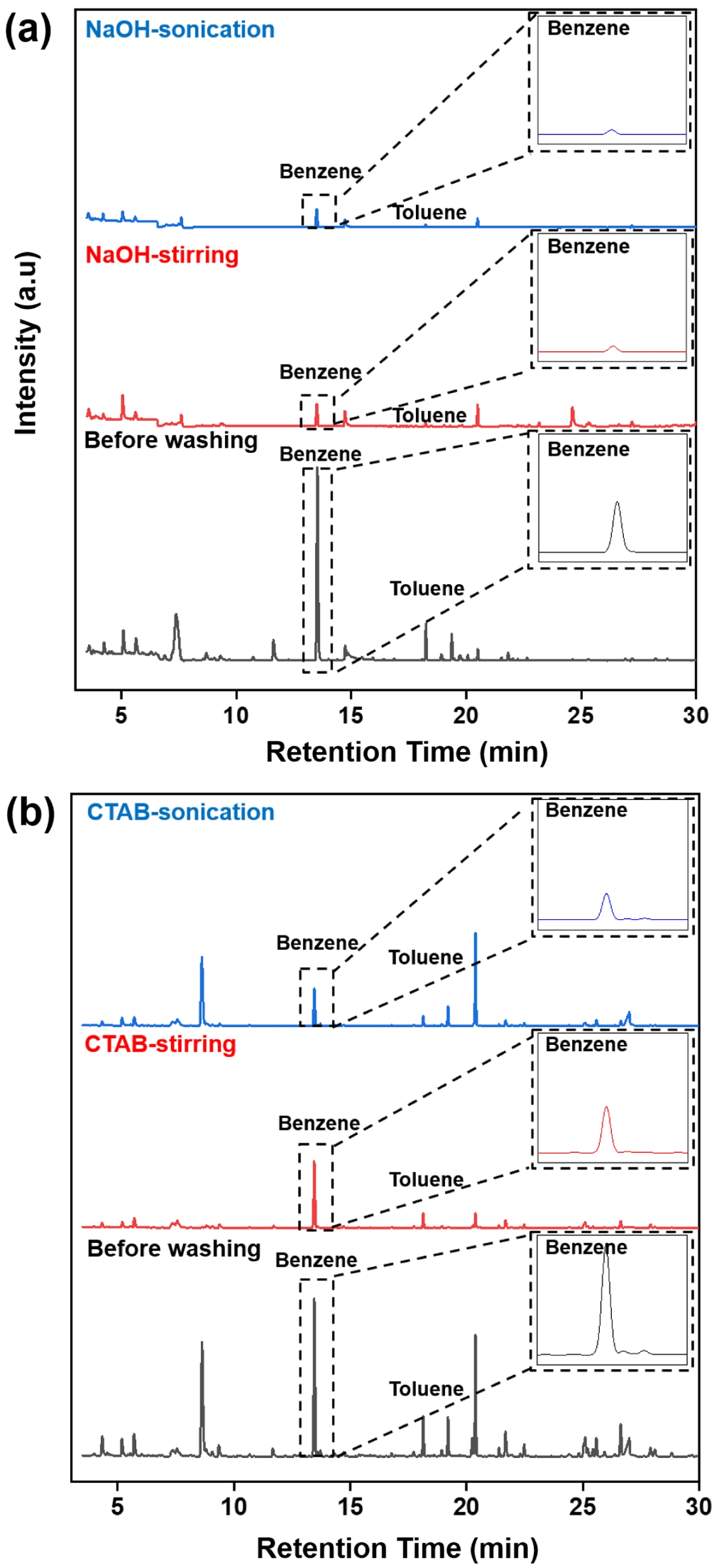

GC-MS. GC–MS analysis was selectively conducted for two representative washing agents: CTAB, which demonstrated relatively high TOC removal efficiency among single-component surfactants, and NaOH, which showed the lowest. This selection aimed to compare the VOC removal performance of agents with contrasting TOC cleaning efficiencies. Since benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes (BTEX) are commonly used as indicators of VOCs, our GC–MS analysis focused on these compounds. The results showed that the signal intensities of all BTEX components were substantially reduced after the washing process, with benzene—initially exhibiting the highest intensity—showing a particularly notable decrease.

Consistent with the TOC results, cleaning by sonication demonstrated greater VOC removal efficiency than stirring. As shown in Figure 4, the intensity of the benzene signal visibly decreased after CTAB-based washing, with further reduction observed when sonication was applied. Similar trends were seen for toluene, ethylbenzene, m, p-xylene, and o-xylene, all of which showed reduced signal intensities after washing, and more pronounced reductions under sonication conditions.

The superior VOC removal by CTAB can be attributed to its surfactant properties. As a cationic surfactant, CTAB reduces the interfacial tension between hydrophobic residues and water, enabling micelle formation that encapsulates volatile organic compounds and disperses them into the aqueous phase. Sonication further enhances this effect by promoting micelle–contaminant interaction through cavitation and agitation.

Interestingly, even NaOH, despite its relatively low TOC removal efficiency, also exhibited notable effectiveness in reducing BTEX signals. This may be explained by the difference in removal mechanisms between high-molecular-weight oil residues TOC and low-molecular-weight VOCs. VOCs, being more volatile and less strongly bound to the polymer matrix, are more easily desorbed from the surface under alkaline conditions. The elevated pH provided by NaOH may destabilize weak interactions such as van der Waals forces or hydrogen bonding between VOC molecules and the substrate. Additionally, NaOH may partially hydrolyze or saponify surface-bound oily contaminants, enhancing the release of adsorbed volatiles. When combined with sonication-induced cavitation, this desorption process becomes even more effective, resulting in substantial VOC reduction. These findings highlight that while CTAB and NaOH operate through different mechanisms, both can effectively remove surface VOCs, particularly when assisted by sonication.

|

Figure 1 (a) FTIR; (b) XRF; (c) TGA of the ELV-derived PA6 composites. |

|

Figure 2 Cross-sectional SEM image of the ELV-derived PA6 composites used in this study. |

|

Figure 3 TOC analysis of the ELV-derived PA6 composites after washing with different cleaning agents at two temperatures: (a) 25 ℃; (b) 70 ℃. The hatched bars represent the samples washed using bath sonication while the solid bars indicate washing with overhead stirring. |

|

Figure 4 GC-MS chromatograms of ELV-derived PA6 composites after washing with (a) NaOH; (b) CTAB. |

|

Table 2 Initial Decomposition Temperature (T5%), the 50% Decomposition Temperature (T50%), 70% Decomposition Temperature (T70%), and the Amount of Residues at 700 °C for the PA6 Composites |

This study investigated the cleaning performance of various washing agents and methods for PA6 composites derived from ELVs to enhance their recyclability. Through a combination of surface characterization techniques including FTIR, SEM, XRF, and TGA, the chemical composition and contaminant distribution of the unwashed composites were examined. Cleaning experiments under different conditions revealed that DD was the most effective agent for removing total organic residues, especially when used at 70 ℃ with sonication. In contrast, NaOH showed relatively low TOC removal, but GC–MS analysis revealed that it was still effective in reducing VOCs, particularly BTEX compounds, when combined with sonication. This difference is attributed to distinct removal mechanisms: CTAB removes both heavy and volatile residues through micelle-assisted solubilization, while NaOH promotes VOC desorption via pH-driven surface destabilization. These findings highlight that tailored washing protocols not only enhance material purity but also reduce volatile emissions, providing a practical and scalable route for improving the quality and environmental performance of recycled thermoplastics recovered from ELVs.

- 1. Slama, M. Ben; Chatti, S.; Chaabene, A.; Ghozia, K.; Touati, H. Z. Design for Additive Manufacturing of Plastic Injection Tool Inserts with Maintenance and Economic Considerations: An Automotive Study Case. J. Manuf. Process 2023, 102, 765-779.

-

- 2. Sateesh, N.; Subbiah, R.; Nookaraju, B. C.; Siva Nagaraju, D. Achieving Safety and Weight Reduction in Automobiles with the Application of Composite Material. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 4469-4472.

-

- 3. Castro, D. M.; Silv Parreiras, F. A Review on Multi-Criteria Decision-Making for Energy Efficiency in Automotive Engineering. Appl. Comput. Informatics 2018, 17, 53-78.

-

- 4. Kawajiri, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Sakamoto, K. Lightweight Materials Equal Lightweight Greenhouse Gas Emissions?: A Historical Analysis of Greenhouse Gases of Vehicle Material Substitution. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 253, 119805.

-

- 5. Abedsoltan, H. Applications of Plastics in the Automotive Industry: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2024, 64, 929-950.

-

- 6. Chauhan, V.; Kärki, T.; Varis, J. Review of Natural Fiber-Reinforced Engineering Plastic Composites, Their Applications in the Transportation Sector and Processing Techniques. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2022, 35, 1169-1209.

-

- 7. Wiese, M.; Thiede, S.; Herrmann, C. Rapid Manufacturing of Automotive Polymer Series Parts: A Systematic Review of Processes, Materials and Challenges. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101582.

-

- 8. Steve, F. The road to auto plastic recovery: recommendations for recycling plastics from end-of-life vehicles, Recycling Product News, August 4, 2022. http://www.recyclingproductnews.com/article/38978.

- 9. Jubinville, D.; Esmizadeh, E.; Saikrishnan, S.; Tzoganakis, C.; Mekonnen, T. A Comprehensive Review of Global Production and Recycling Methods of Polyolefin (PO) Based Products and Their Post-Recycling Applications. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2020, 25, e00188.

-

- 10. OECD. Global Plastics Outlook; Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options: Paris, 2022.

-

- 11. Jin, H.; Yu, J.; Okubo, K. Life Cycle Assessment on Automotive Bumper: Scenario Analysis Based on End-of-Life Vehicle Recycling System in Japan. Waste Manag. Res. 2022, 40, 765-774.

-

- 12. Miller, L.; Soulliere, K.; Sawyer-Beaulieu, S.; Tseng, S.; Tam, E. Challenges and Alternatives to Plastics Recycling in the Automotive Sector. Materials (Basel) 2014, 7, 5883-5902.

-

- 13. Roosen, M.; Harinck, L.; Ügdüler, S.; De Somer, T.; Hucks, A. G.; Belé, T. G. A.; Buettner, A.; Ragaert, K.; Van Geem, K. M.; Dumoulin, A.; De Meester, S. Deodorization of Post-Consumer Plastic Waste Fractions: A Comparison of Different Washing Media. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 812, 152467.

-

- 14. Dutra, C.; Pezo, D.; Freire, M. T. de A.; Nerín, C.; Reyes, F. G. R. Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds in Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate and High-Density Polyethylene by Headspace Solid Phase Microextraction Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry to Evaluate the Efficiency of Recycling Processes. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 1319-1330.

-

- 15. Lattuati-Derieux, A.; Egasse, C.; Thao-Heu, S.; Balcar, N.; Barabant, G.; Lavédrine, B. What Do Plastics Emit? HS-SPME-GC/MS Analyses of New Standard Plastics and Plastic Objects in Museum Collections. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 238-247.

-

- 16. Gorny, S.; Bichler, S.; Stamminger, R.; Seifert, M.; Kessler, A.; Wrubbel, N. Effects of Relevant Detergent Components on the Cleaning Performance in Low Temperature Electric Household Dishwashing. Tenside Surf. Deterg. 2016, 53, 478-486.

-

- 17. Mindivan, A. F. Effect of Crystalline Form (γ) of Polyamide 6 / Graphene Nanoplatelets (PA 6/GN) Nanocomposites on Its Structural and Thermal Properties. Mech. Technol. Mater. 2016, 10, 56-59.

- 18. Jiang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Fei, J.; Qin, Z.; Yin, X.; Sun, H.; Sun, Y. Transport of Different Microplastics in Porous Media: Effect of the Adhesion of Surfactants on Microplastics. Water Res. 2022, 215, 118262.

-

- 19. Fainerman, V. B.; Aksenenko, E. V.; Kovalchuk, V. I.; Mucic, N.; Javadi, A.; Liggieri, L.; Ravera, F.; Loglio, G.; Makievski, A. V.; Schneck, E.; Miller, R. New View of the Adsorption of Surfactants at Water/Alkane Interfaces – Competitive and Cooperative Effects of Surfactant and Alkane Molecules. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 279, 102143.

-

- 20. Nahid, H. Liquids and a Commercial Anionic Surfactant In Demulsifying Crude Oil In Water Emulsion. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Northern British Columbia, BC, December 2022.

-

- 21. Zhang, H.; Dong, M.; Zhao, S. Experimental Study of the Interaction between NaOH, Surfactant, and Polymer in Reducing Court Heavy Oil/Brine Interfacial Tension. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 3644-3650.

-

- 22. Lichinga, K. N.; Luanda, A.; Sahini, M. G. A Novel Alkali-Surfactant for Optimization of Filtercake Removal in Oil-Gas Well. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2022, 12, 2121-2134.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2026; 50(1): 144-150

Published online Jan 25, 2026

- 10.7317/pk.2026.50.1.144

- Received on Aug 12, 2025

- Revised on Dec 16, 2025

- Accepted on Dec 16, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Yun-Seok Jun

-

Department of Polymer Engineering, Pukyong National University, 45 Yongso-ro, Nam-gu, Busan 48513, Korea

- E-mail: ysjun@pknu.ac.kr

- ORCID:

0000-0002-6488-6213

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.