- Effect of Nanocellulose Surface Modification with Different Silane Coupling Agents on the Mechanical Properties of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composite

Ellana Nabilah Nur Averina Ansar, Ki-Se Kim*, PilHo Huh**,†

, and Seong Il Yoo†

, and Seong Il Yoo†

Department of Polymer Engineering, Pukyong National University, Busan 48513, Korea

*Department of Integrative Engineering for Hydrogen Safety, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, Korea

**Department of Polymer Science and Engineering, Pusan National University, Busan 46241, Korea.- 실란 커플링제를 활용한 나노셀룰로오스 표면개질이 열가소성 폴리우레탄 복합체의 기계적 물성에 미치는 영향

부경대학교 고분자공학과, *강원대학교 수소안전융합학과, **부산대학교 고분자공학과

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

Polymer composites have attracted widespread interest due to their versatile properties and broad applications across various industries, including biomedical, aerospace, electronics, and packaging. In this study, thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) composites were fabricated via a melt-mixing process with nanocellulose, a biomass-based nanofiller known for its sustainability and mechanical potential. To improve the compatibility between hydrophilic nanocellulose and hydrophobic TPU matrix, cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) were surface-modified with two different silane coupling agents: 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) and octyltriethoxysilane (OTES). Cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) were also utilized for comparison as a distinct type of nanocellulose. Mechanical test revealed that the incorporation of nanocellulose reduced the tensile strength and elongation at break of TPU composites. Nevertheless, stiffness was generally enhanced, particularly with surface-modified CNCs. These results highlight the importance of the surface chemistry of nanofillers in engineering the mechanical performance of TPU-based nanocomposites.

고분자 복합체는 생체의료, 항공우주, 전자, 포장 등 다양한 산업 분야에서 우수한 특성과 폭넓은 응용 가능성으로 인해 큰 관심을 받고 있다. 본 연구에서는 바이오매스 기반 나노필러인 나노셀룰로오스를 열가소성 폴리우레탄(TPU)과 용융 혼합하여 복합체를 제조하였다. 친수성 나노셀룰로오스와 소수성 TPU 매트릭스 간의 상용성을 개선하기 위해, CNC의 표면을 3-아미노프로필트라이에톡시실란(APTES)과 옥틸트라이에톡시실란(OTES)이라는 두 가지 실란 커플링제를 이용해 개질하였다. 또한, 비교를 위해 셀룰로오스 나노섬유(CNF)를 활용한 복합체도 함께 제조하였다. 기계적 물성 평가 결과, CNC의 도입은 TPU 복합체의 인장 강도와 파단 신율을 감소시켰으나, 표면 개질된 CNC를 사용한 경우 강성은 향상되는 경향을 보였다. 이러한 결과는 TPU 기반 나노복합재의 기계적 성능을 설계함에 있어 나노필러의 표면 화학이 중요한 역할을 한다는 것을 보여준다.

In this study, nanocellulose was surface-modified using various silane coupling agents to tailor the interfacial interactions between the polymer matrix and the filler. After confirming the success of the surface modification, the treated nanocellulose was incorporated into a thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) matrix via melt mixing. Our study exemplifies the importance of the surface chemical structures of nanofillers in engineering the mechanical performance of TPU-based nanocomposites.

Keywords: nanocellulose, thermoplastic polyurethane, composites, silane coupling agents.

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (RS-2024-00433823, Production technology development of bio polyamide66 advanced material product based on starch (sugar) byproducts for future transport internal & external components/modules) and Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program (20010807, Bio tackifier adhesive material with a biomass content of 50% or more) funded By the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

The use of biomass-derived nanofillers, including nanocellulose, chitin/chitosan nanomaterials, and lignin nanoparticles, for the mechanical reinforcement of polymers represents a promising sustainable strategy in polymer composite development. Unlike traditional inorganic fillers, which do not biodegrade in nature and contribute to long-term environmental issues, biomass-derived nanofillers offer an eco-friendly alternative.1 In this context, nanocellulose is particularly interesting due to its natural abundance, high mechanical strength, and low density.2 These characteristics, coupled with biodegradability and biocompatibility, make it an ideal choice for sustainable nanofillers to reinforce polymer composites. Cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) and cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) are two representative forms of nanocellulose, distinguished by their structural characteristics and physicochemical properties. CNCs are rod-shaped, crystalline particles typically produced through acid hydrolysis of cellulose sources.3 In contrast, the production of CNFs generally involves mechanical treatment such as high-shear refining or homogenization, resulting in a long fibrillar structures with alternating crystalline and amorphous regions.4-7

Both CNCs and CNFs possess abundant surface hydroxyl groups, enabling chemical modification and strong interfacial interactions with hydrophilic polymers. They have been homogeneously dispersed in hydrophilic polymer matrices such as poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO),8-12 poly(acrylic acid) (PAA),13,14 and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA).15-18 When combined with these polymers, nanocellulose significantly enhances the mechanical properties of the resulting composites through efficient load transfer and, in some cases, the formation of percolated networks. CNCs, with their high crystallinity and rod-like morphology, can effectively improve stiffness and dimensional stability, whereas CNFs, composed of long and flexible fibrils, can form interconnected networks that improve toughness. On the contrary, in hydrophobic polymers such as thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), the inherent incompatibility between nanocellulose and the hydrophobic polymer matrix, along with nanocellulose’s strong tendency to self-aggregate through hydrogen bonds, often leads to phase separation and weak interfacial bonding, reducing the mechanical properties of the composites.19,20

Surface modification techniques such as alkylation, acetylation, silane coupling reactions, or grafting with hydrophobic functional groups can be employed to address the compatibility between nanocellulose and hydrophobic polymers.21-25 Alkoxysilanes are typically used for surface modification to enhance dispersion and improve interfacial interaction between polymers and fillers.26 In this study, we modified the surface of nanocellulose using silane coupling agents and compared the mechanical reinforcement effect of the modified and unmodified nanocellulose (CNC and CNF) in TPU composites prepared via the melt-compounding method.

Materials. CNCs and CNFs were purchased from CelluForce (Canada) and Cellullose Lab Inc. (Canada), respectively. Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU, Elastollan 1185A) was obtained from BASF (Germany). (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES), octyltriethoxysilane (OTES), and acetic acid (> 99.5%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Ethanol 99.9% was supplied from Duksan Pure Chemicals (South Korea). All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

Surface Modification of Nanocellulose. The surface of CNC was modified as previously described in the literature with a minor modification.27 First, the silane agents (5 wt%) were diluted in an ethanol-water mixture (80:20) and stirred for 2 h. Then, the pH was adjusted using acetic acid until it reached ~4. An acidic environment is usually utilized to catalyze the hydrolysis rate of alkoxysilane while slowing down the condensation of silanols. In a separate vial, 5 wt% of CNC was dispersed in an ethanol-water mixture (80:20) and stirred for 2 h. The silane solution was then added to the CNC dispersion and stirred for an additional 2 h. After centrifuging the mixture at 2500 rpm for 20 min, it was washed with deionized water. This centrifugation–washing step was repeated twice. Subsequently, the samples were freeze-dried for approximately 2 days, and then heated at 120 ℃ for 2 h under vacuum.

TPU Composites Fabrication. To prepare TPU composites, TPU pellets and nanocellulose (CNCs or CNFs) were first pre-mixed in ethanol. Nanofiller contents were 0, 1, and 3 wt% relative to the total weight of TPU and nanofillers. The TPU and nanofillers were placed in a glass beaker, and ethanol was added to cover the materials. Subsequently, the mixture was gently stirred using a spatula to promote homogeneous dispersion. The mixture was then placed in a convection oven at 60 ℃ overnight to evaporate the ethanol, resulting in a uniform coating of nanofillers on the surface of the TPU pellets. After that, the pre-mixed TPU and nanofillers were fed into a batch-type dispersion mixer (GPT-100, Green Polytech), melted at 180 ℃ or 190 ℃, and mixed for 5-10 min with a rotating screw (speed = 20 rpm). The composites were then compression-molded into dog-bone shapes at 220 ℃ under a pressure of 5 tons. The final thickness of the composite films was approximately 0.2 mm.

Characterization. Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) images were collected using MAGNA (TESCAN) with an acceleration voltage of 3 kV. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was obtained using AXIS SUPRA (KRATOS Analytical Ltd.). Tensile tests were performed using Bluehill Elements (Instron) with a 1 kN load cell at a 50 mm/min crosshead speed.

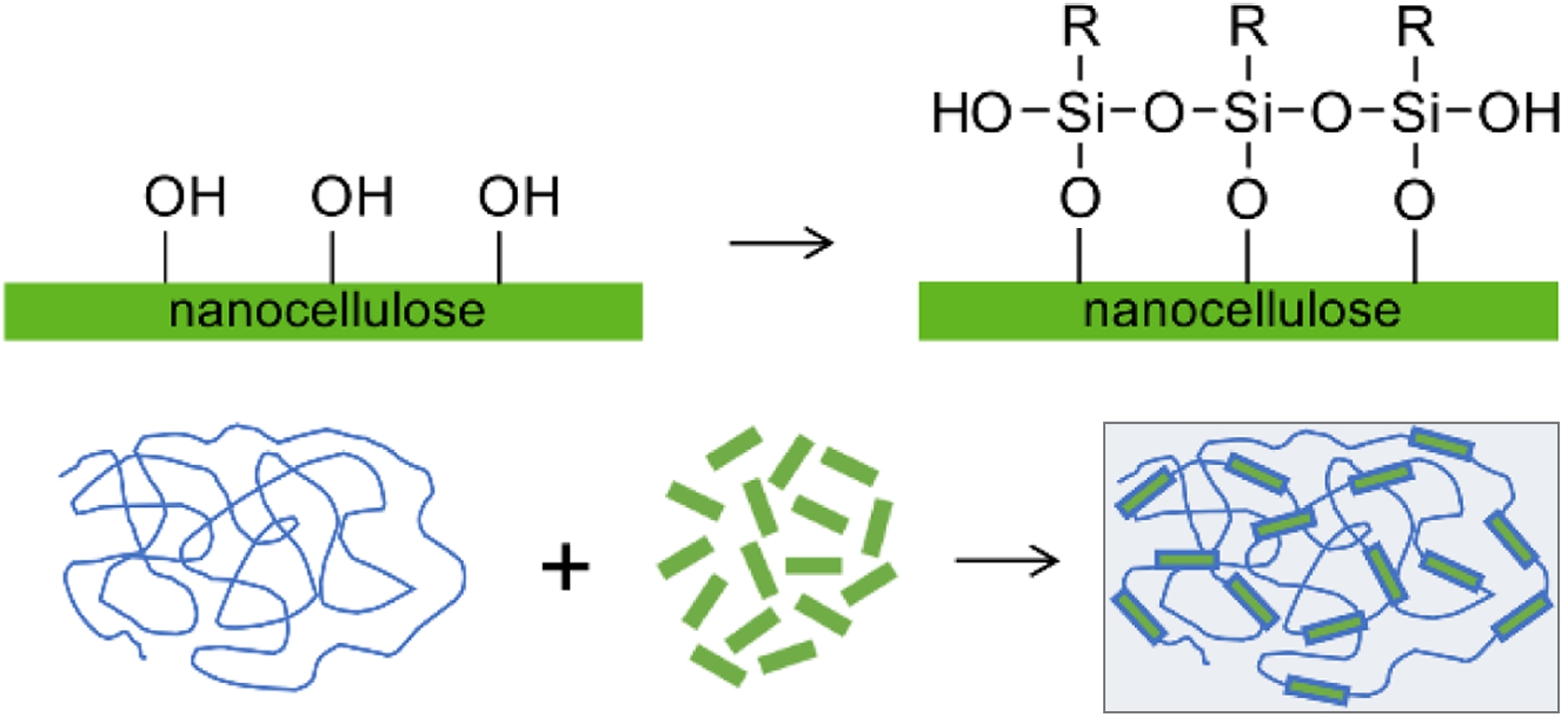

Although nanocellulose has great potential as a sustainable nanofiller for mechanical reinforcement of polymers,28,29 its inherent hydrophilicity often results in poor compatibility with hydrophobic polymer matrices. In this regard, organosilanes are commonly employed as coupling agents to enhance the interfacial interaction between the matrix and fillers.30 The silane coupling reaction involves sequential hydrolysis and condensation steps. In the presence of water or an ethanol-water mixture, the alkoxy groups (-OR) of the silane coupling agents are hydrolyzed to form silanol groups (-Si-OH). These silanol groups can subsequently undergo condensation reactions with one another, leading to the formation of a siloxane (-Si-O-Si) polymer network in the solution. Upon heating, hydrogen bonds between silanol groups and CNC hydroxyl groups can transform into covalent -Si-O-C linkages, while remaining silanol groups on cellulose may undergo further condensation.31,32 Scheme 1 illustrates the surface modification process and fabrication of TPU composites.

Scheme 1. Scheme of surface modification of CNC by silane coupling agents and fabrication of TPU composite. R represents –(CH2)3NH2 for APTES and –(CH2)7CH3 for OTES.

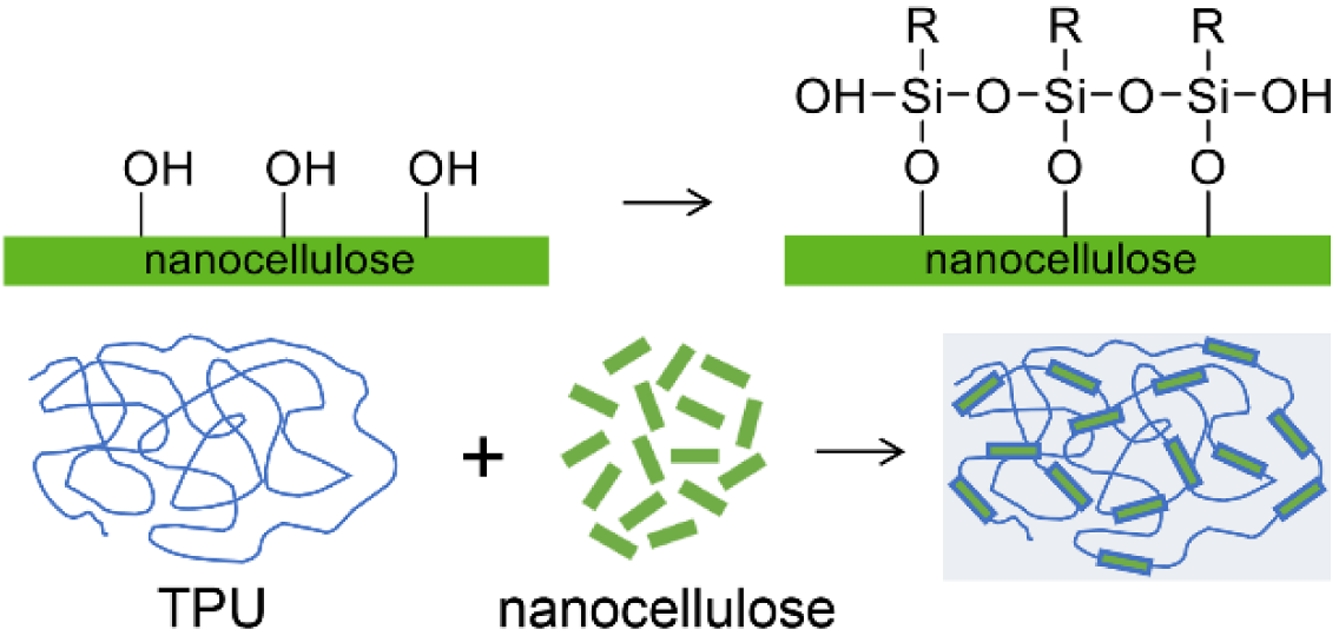

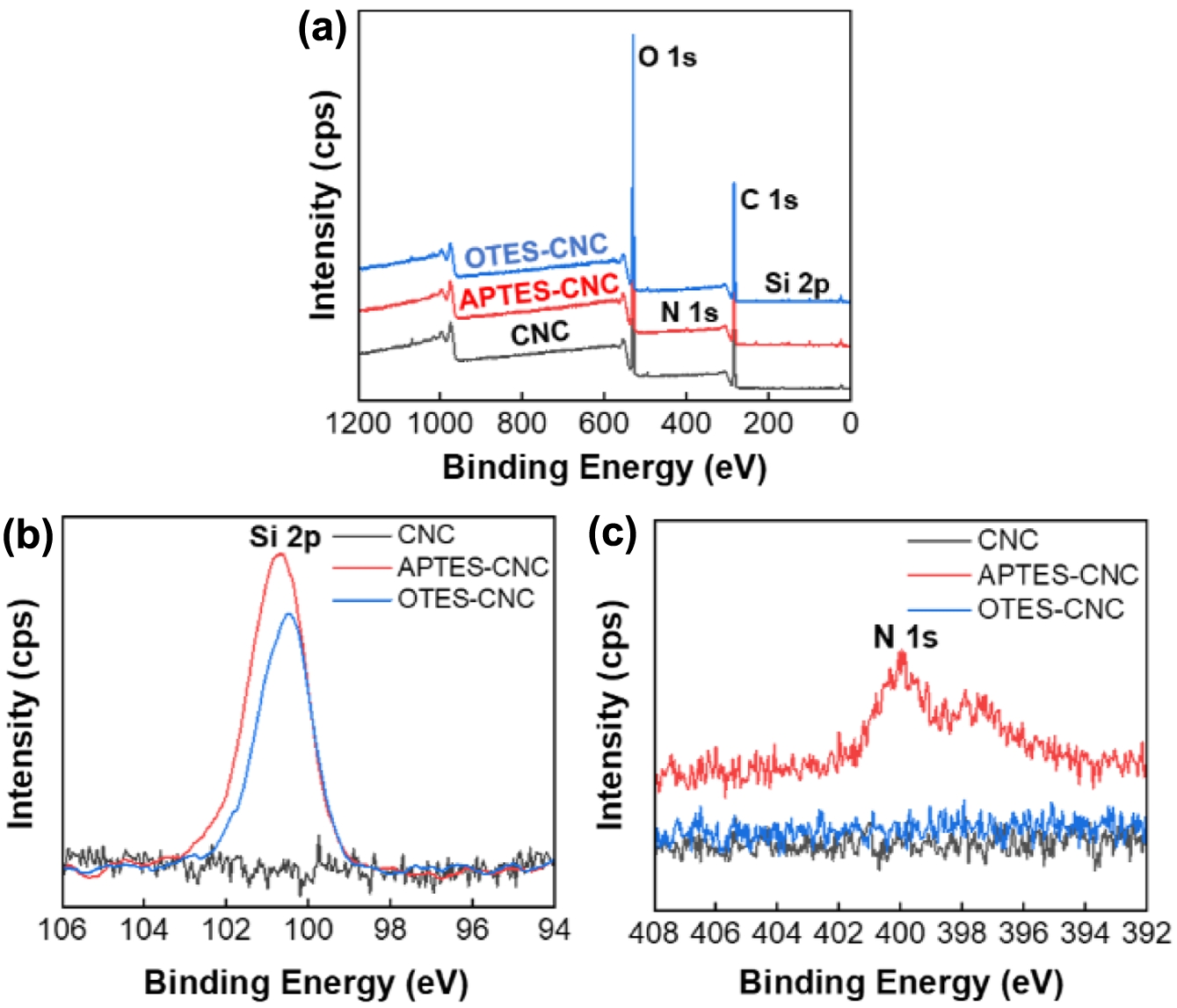

Prior to composite preparation, SEM analysis was conducted to evaluate the morphology of the nanofillers. As shown in Figure 1(a), CNCs have short and rod-like structures primarily composed of crystalline regions. In contrast, CNFs (Figure 1(b)) exhibited thicker and longer fibrils consisting of both crystalline and amorphous regions of cellulose.33 After surface modification, both APTES-CNC (Figure 1(c)) and OTES-CNC (Figure 1(d)) maintained the original rod-like structure of CNC. In addition, OTES-CNC exhibited reduced aggregation compared to APTES-CNC, likely due to the presence of alkyl chains on the nanocellulose surface.34

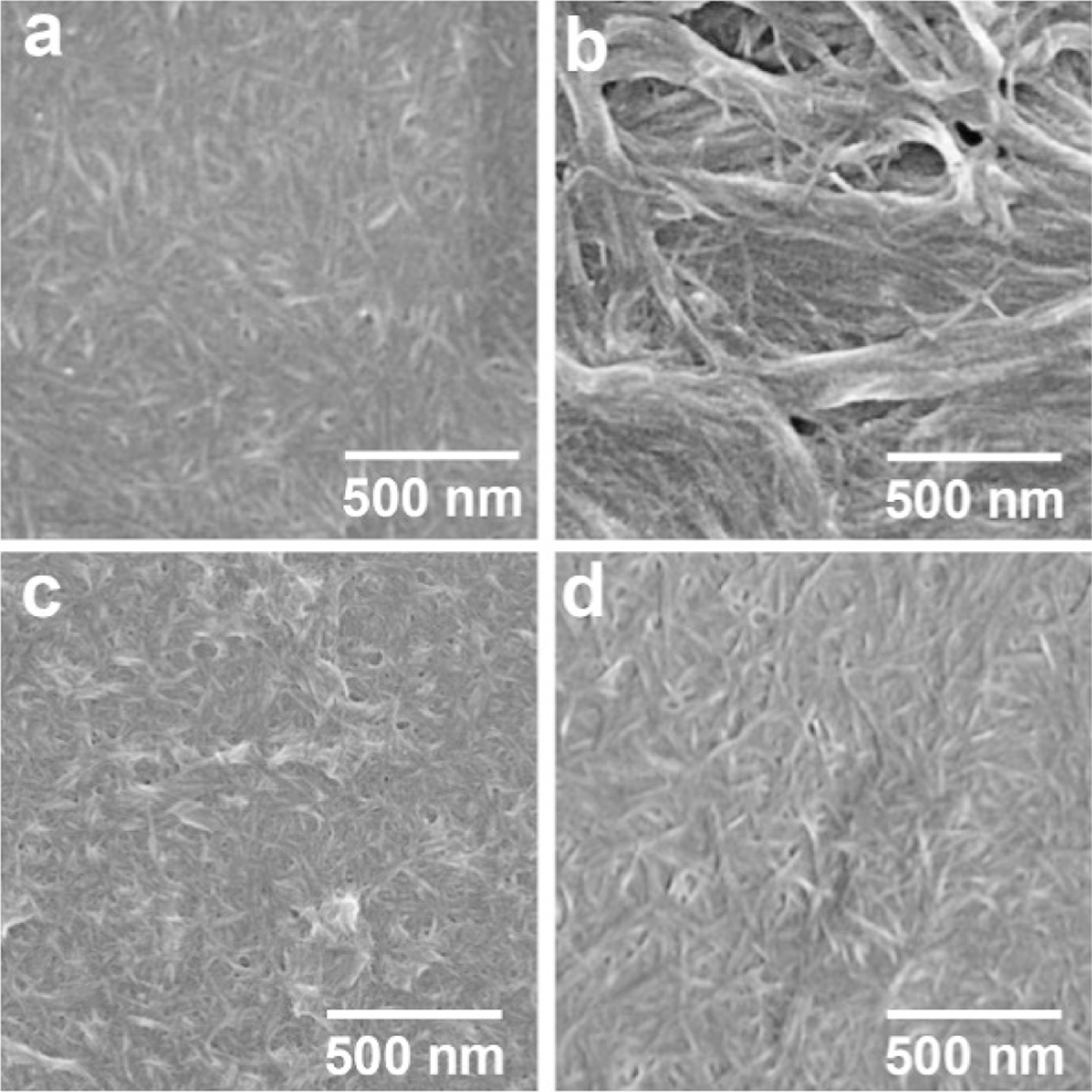

XPS analysis was performed to compare the surface chemical structures of pristine and surface-modified CNCs. As shown in Figure 2(a), all samples exhibited characteristic peaks corresponding to C 1s (~285 eV) and O 1s (~533 eV). The high-resolution spectra (Figure 2(b)) further confirmed the presence of Si 2p peaks in the APTES-CNC (red line) and OTES-CNC (blue line), whereas the Si 2p signal was absent in the pristine CNC, indicating successful surface modification. Furthermore, a distinct N 1s signal observed only in APTES-CNC (Figure 2(c)), with peaks at 398.1 eV and 400.2 eV corresponding to NH2 and NH3⁺ groups, respectively, confirms the presence of amine functionalities introduced by APTES.35-41 The C 1s atomic concentration also increased upon silane functionalization. Specifically, the C 1s content increased from 54.1% in pristine CNC to 56.5% for APTES-CNC and 58.5% for OTES-CNC, respectively.

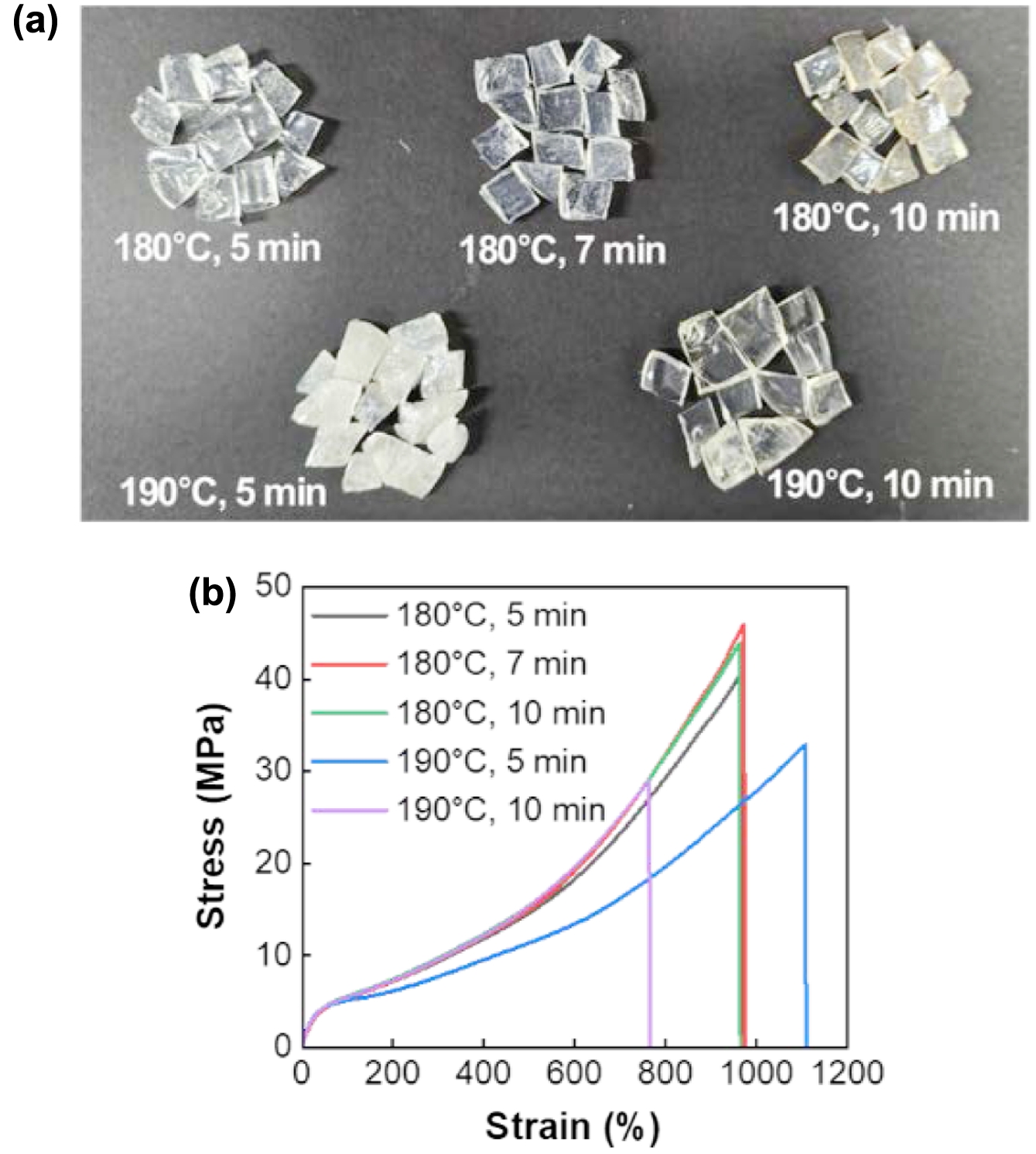

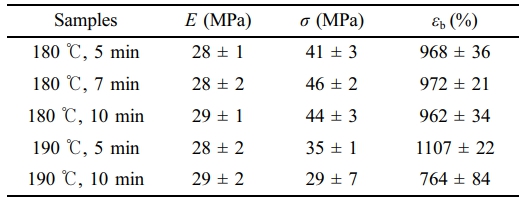

After confirming the success of the surface modification, the nanofillers were incorporated into thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) via melt blending. To determine the optimal processing conditions, preliminary tests were conducted using pristine TPU at two temperatures (180 ℃ and 190 ℃) with compounding times of 5, 7, and 10 min. Based on visual inspection (Figure 3(a)), the TPU processed at 180 ℃ for 5 and 7 min appeared relatively transparent and colorless. Noticeable yellowing was observed in samples processed for 10 min at 180 ℃ and 190 ℃, indicating thermal degradation of the composites. In addition, the sample processed at 190 ℃ for 5 min appeared opaque, possibly due to the increased crystallinity or microstructural changes.

The composites were subsequently compressed into dog-bone specimens at 220 ℃. Following this, UTM tests were conducted to evaluate the mechanical properties. The resulting stress−strain curves were plotted in Figure 3(b), and the corresponding mechanical properties under different processing conditions are summarized in Table 1. As found, the Young’s Modulus of the TPU films showed only slight variations across all processing conditions, whereas the tensile strength and elongation at break were decreased at elevated temperatures, likely due to thermal degradation. The highest Young’s modulus was observed in samples processed at 180 ℃ for 10 min, while the highest tensile strength was found in samples processed at 180 ℃ for 7 min. Based on the UTM results and visual appearance, the condition of 180 ℃ for 7 min was selected for the preparation of TPU composites with nanofillers.

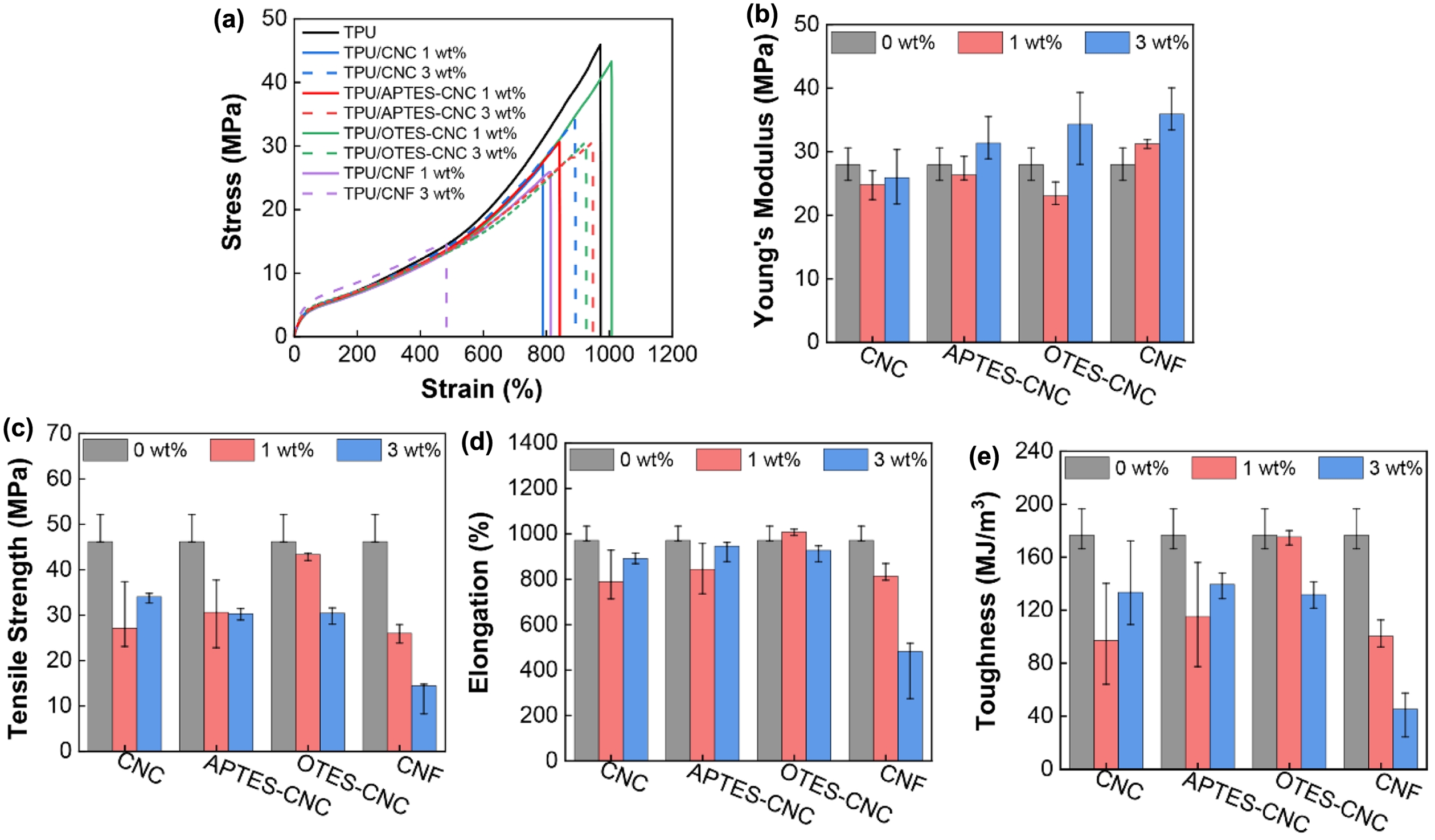

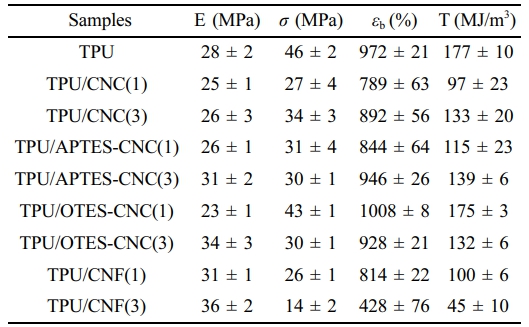

After determining the optimum processing condition, TPU/nanocellulose composites were prepared by premixing TPU pellets and nanofillers in ethanol. The mixtures were then placed in a convection oven at 60 ℃ to evaporate ethanol, resulting in a uniform nanocellulose coating on the TPU pellets. This pre-coating was expected to facilitate better nanocellulose dispersion during melt mixing at 180 ℃. The resulting composites were subsequently compression-molded into dog-bone specimens at 220 ℃ for UTM measurement. In Figure 4(a), the neat TPU exhibited Young’s modulus of 28 MPa, an ultimate tensile strength of 46 MPa, an elongation at break of 972%, and a toughness of 177 MJ/m3, respectively. The introduction of unmodified CNCs led to a reduction in the mechanical properties of the composite films. For instance, at 1 wt% CNC loading, the Young’s modulus, tensile strength, elongation at break, and toughness decreased to 25 MPa, 27 MPa, 789%, and 97 MJ/m3, respectively. This reduction is likely due to the poor compatibility and aggregation of CNCs within the TPU matrix.

Surface-modified CNCs and CNFs affected the Young’s modulus of TPU composites in a dose-dependent manner, with a decrease observed at 1.0 wt% and an increase at 3.0 wt% (Figure 4(b)), suggesting that higher nanofiller content contributes to the enhanced stiffness. However, the tensile strength decreased in all cases (Figure 4(c)), likely due to filler agglomeration and the resulting formation of stress concentration sites. Among the samples, OTES-CNC showed the greatest resistance to the reduction in tensile strength, possibly due to its improved dispersion compared to other fillers. The elongation at break remained largely unchanged (Figure 4(d)), except for the CNF-filled TPU composites, which exhibited a significant reduction. This reduction might be attributed to the high aspect ratio of CNFs, which likely exacerbates the incompatibility with the TPU matrix. Similarly, the toughness (Figure 4(e)) decreased in the TPU composites compared to neat TPU, indicating reduced energy absorption, while OTES-modified CNCs retained relatively higher values. Although surface modification could improve the interfacial compatibility between CNCs and the TPU matrix, achieving uniform dispersion remains challenging. The increase in Young’s modulus at higher filler loadings indicates partial reinforcement, whereas the decrease in tensile strength and toughness suggest the presence of aggregation or weak interfacial adhesion. Based on the mechanical behavior, OTES-CNC was inferred to have relatively better dispersion, likely due to the alkyl chains reducing aggregation. Detailed mechanical properties of the TPU/nanocellulose composite films are summarized in Table 2.

A similar observation was reported by Larraza et al.42 in water-born polyurethane/CNF nanocomposites, where a decrease in elongation at break at higher CNF contents was attributed to the formation of agglomerates. Likewise, Barick et al.43 prepared TPU/vapor-grown carbon nanofiber composites via melt compounding and observed a comparable trend, indicating that the presence of rigid nanofillers reduces ductility and increases stiffness. Consistent behaviors were also reported by Prataviera et al.,44 who prepared TPU/CNC composite films through melt-mixing with CNC contents ranging from 0.1 to 5 wt%. In their study, the addition of a small amount of CNC (0.1 wt%) led to a decrease in the elongation and tensile strength, while slightly enhancing Young’s Modulus. As the filler content increased, the stiffness of the composite films increased, with 5 wt% having the highest Young’s Modulus.

|

Figure 1 FE-SEM images of (a) CNC; (b) CNF; (c) APTES-CNC; (d) OTES-CNC. All the fillers were dispersed in H2O at a concentration of 0.5 wt%. |

|

Figure 2 XPS spectra of pristine CNC, APTES-CNC, and OTESCNC: (a) survey spectra; (b) high-resolution Si 2p spectra; (c) highresolution N 1s spectra. |

|

Figure 3 (a) Photographs of TPU processed under varying conditions; (b) their corresponding stress–strain behavior. |

|

Figure 4 Mechanical properties of TPU/nanocellulose composites: (a) Representative mechanical profile (stress–strain curves); (b) Young’s modulus; (c) tensile strength; (d) elongation at break; (e) toughness. Nanocellulose contents are represented as gray (0 wt%), red (1 wt%), and blue (3 wt%). |

|

Table 1 Mechanical Properties of Pristine TPU Composites |

E: Young’s modulus, s: tensile strength, eb: elongation at break |

|

Table 2 Mechanical Properties of TPU/nanocellulose Composites |

E: Young’s modulus, σ: tensile strength, εb: elongation at break, T: toughness. Values in parentheses indicate the nanocellulose content (wt%) |

Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) composites were prepared via melt blending using various forms of nanocellulose, including unmodified CNCs, silane-functionalized CNCs (APTES-CNC and OTES-CNC), and CNFs. While the incorporation of nanocellulose led to reductions in tensile strength and elongation at break, the overall stiffness of the composites, as indicated by the increased Young’s modulus, was enhanced. Overall, this study highlights the importance of optimizing both the filler type and surface chemistry to tailor the mechanical performance of TPU-based nanocomposites.

- 1. Kim, H. J.; Choi, Y. H.; Jeong, J. H.; Kim, H.; Yang, H. S.; Hwang, S. Y.; Koo, J. M.; Eom, Y. Rheological Percolation of Cellulose Nanocrystals in Biodegradable Poly(butylene succinate) Nanocomposites: A Novel Approach for Tailoring the Mechanical and Hydrolytic Properties. Macromol. Res. 2021, 29, 720-726.

-

- 2. Habibi, Y.; Lucía, L.; Rojas, O. J. Cellulose Nanocrystals: Chemistry Self-Assembly and Applications. Chemical Reviews 2010, 110, 3479-3500.

-

- 3. Wang, Q. Q.; Zhu, J. Y.; Reiner, R. S.; Verril, S. P.; Baxa, U.; McNeil, S. E. Approaching Zero Cellulose Loss in Cellulose Nanocrystal (CNC) Production: Recovery and Characterization of Cellulosic Solid Residues (CSR) and CNC. Cellulose 2012,19, 2033-2047.

-

- 4. Henriksson, M.; Berglund, L. A.; Isaksson, P.; Lindström, T.; Nishino, T. Cellulose Nanopaper Structures of High Toughness. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 1579-1585.

-

- 5. Iwamoto, S.; Nakagaito, A. N.; Yano, H. Nano-fibrillation of Pulp Fibers for the Processing of Transparent Nanocomposites. Appl. Phys. A. 2007, 89, 461-466.

-

- 6. Wang, Q. Q.; Zhu, J. Y.; Gleisner, R.; Kuster, T. A.; Baxa, U.; McNeil, S. E. Morphological Development of Cellulose Fibrils of A Bleached Eucalyptus Pulp by Mechanical Fibrillation. Cellulose 2012,19, 1631-1643.

-

- 7. Ansar, E. N. N. A.; Biutty, M. N.; Kim, K. S.; Yoo, S.; Huh, P.; Yoo, S. I. Sustainable Polyamide Composites Reinforced with Nanocellulose via Melt Mixing Process. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 419.

-

- 8. Shi, Z.; Xu, H.; Yang, Q.; Xiong, C.; Zhao, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Saito, T.; Isogai, A. Carboxylated Nanocellulose/Poly(ethylene oxide) Composite Films as Solid-Solid Phase-Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 225, 115215.

-

- 9. Safdari, F.; Carreau, P. J.; Heuzey, M. C.; Kamal, M. R.; Sain, M. M. Enhanced Properties of Poly(ethylene oxide)/Cellulose Nanofiber Biocomposites. Cellulose 2017, 24, 755-767.

-

- 10. Zhou, C.; Chu, R.; Wu, R.; Wu, Q. Electrospun Polyethylene Oxide/Cellulose Nanocrystal Composite Nanofibrous Mats with Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Microstructures. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 2617-2625.

-

- 11. Park, W. I.; Kang, M.; Kim, H. S.; Jin, H. J. Electrospinning of Poly(ethylene oxide) with Bacterial Cellulose Whiskers. Macromol. Symp. 2007, 249, 289-294.

-

- 12. Surov, O. V.; Voronova, M. I.; Afineesvskii, A. V.; Zakharov, A. G. Polyethylene Oxide Films Reinforced by Cellulose Nanocrystals: Microstructure-Properties Relationship. Carbohydr. Polym.2018, 181, 489-498.

-

- 13. Lu, P.; Hsieh, Y. L. Cellulose Nanocrystal-Filled Poly(acrylic acid) Nanocomposite Fibrous Membranes. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 415604.

-

- 14. Yang, J.; Han, C. R.; Duan, J. F.; Ma, M. G.; Zhang, X. M.; Xu, F.; Sun, R. C.; Xie, X. M. Studies on the Properties and Formation Mechanism of Flexible Nanocomposites Hydrogels from Cellulose Nanocrystals and Poly(acrylic acid). J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 22467-22480.

-

- 15. George, J.; Ramana, K. V.; Bawa, A. S. Siddaramaiah. Bacterial Cellulose Nanocrystals Exhibiting High Thermal Stability and Their Polymer Nanocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 48, 50-57.

-

- 16. Qua, E. H.; Hornsby, P. R.; Sharma, H. S.; Lyons, G.; McCall, R. D. Preparation and Characterization of Poly(vinyl alcohol) Nanocomposites Made from Cellulose Nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 113, 2238-2247.

-

- 17. Jalal Uddin, A..; Araki, J.; Gotoh, Y. Toward ¡°strong¡± Green Nanocomposites: Polyvinyl Alcohol Reinforced with Extremely Oriented Cellulose Whiskers. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 617-624.

-

- 18. Kim, J. W.; Park, H.; Lee, G.; Jeong, Y. R.; Hong, S. Y.; Keum, K.; Yoon, J.; Kim, M. S.; Ha, J. S. Paper-like, Thin, Foldable, and Self-Healable Electronics Based on PVA/CNC Nanocomposite Film. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1905968.

-

- 19. Kim, Y.; Huh, P.; Yoo, S. I. Mechanical Reinforcement of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Nanocomposites by Surface-Modified Nanocellulose. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2023, 224, 2200383.

-

- 20. Nicharat, A.; Shirole, A.; Foster, E. J.; Weder, C. Thermally Activated Shape Memory Behavior of Melt-Mixed Polyurethane/Cellulose Nanocrystal Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45033.

-

- 21. Lee, J. H.; Park, S. H.; Kim, S. H. Surface Alkylation of Cellulose Nanocrystals to Enhance Their Compatibility with Polylactide. Polymers 2020, 12, 178.

-

- 22. Lepetit, A.; Drolet, R.; Tolnai, B.; Montplaisir, D.; Zerrouki, R. Alkylation of Microfibrillated Cellulose – A Green and Efficient Method For Use in Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Polymer 2017, 126, 48-55.

-

- 23. Yue, L.; Maiorana, A.; Khelifa, F.; Patel, A.; Raquez, J. M.; Bonnaud, L.; Gross, R.; Dubois, P.; Manas-Zloczower, I. Surface-Modified Cellulose Nanocrystals for Biobased Epoxy Nanocomposites. Polymer 2018, 134, 155-162.

-

- 24. Do, T. T. A.; Grijalvo, S.; Imae T.; Garcia-Celma, M. J.; Rodríguez-Abreu, C. A Nanocellulose-Based Platform Towards Targeted Chemo-photodynamic/Photothermal Cancer Therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118366.

-

- 25. Lin, N.; Huang, J.; Chang, P. R.; Feng, J.; Yu, J. Surface Acetylation of Cellulose Nanocrystal and Its Reinforcing Function in Poly(lactic acid). Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 1834-1842.

-

- 26. Frank, B. P.; Durkin, D. P.; Caudill, E. R.; Zhu, L.; White, D. H.; Curry, M. L.; Pedersen, J. A.; Fairbrother, D. H. Impact of Silanization on the Structure, Dispersion Properties, and Biodegradability of Nanocellulose as a Nanocomposite Filler. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.2018, 1, 7025-7038.

-

- 27. Abdelmouleh, M.; Boufi, S.; Belgacem, M. N.; Duarte, A. P.; Ben Salah, A.; Gandini, A. Modification of Cellulosic Fibres with Functionalised Silanes: Development of Surface Properties. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2004, 24, 43-54.

-

- 28. Taib, M. N. A. M.; Hamidon, T. S.; Garba, Z. N.; Trache, D.; Uyama, H.; Hussin, M. H. Recent Progress in Cellulose-Based Composites Towards Flame Retardancy Applications. Polymer 2022, 244, 124677.

-

- 29. Joseph, B.; Sagarika, V.K.; Sabu, C.; Kalarikkal, N.; Thomas, S. Cellulose Nanocomposites: Fabrication and Biomedical Applications. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2020, 5, 223-237.

-

- 30. Robles, E.; Csóka, L.; Labidi, J. Effect of Reaction Conditions on the Surface Modification of Cellulose Nanofibrils with Aminopropyl Triethoxysilane. Coatings 2018,8, 139.

-

- 31. Pacaphol, K.; Aht-Ong, D. The Influences of Silanes on Interfacial Adhesion and Surface Properties of Nanocellulose Film Coating on Glass and Aluminum Substrates. Surface and Coatings Technology 2017, 320, 70-81.

-

- 32. Xie, Y.; Hill, C. A. S.; Xiao, Z.; Militz, H.; Mai, C. Silane Coupling Agents Used for Natural Fiber/Polymer Composites: A review. Composites: Part A 2010, 41, 806-819.

-

- 33. Xu, X.; Liu, F.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, J. Y.; Haagenson, D.; Wiesenborn, D. P. Cellulose Nanocrystals vs Cellulose Nanofibrils: A Comparative Study on Their Microstructures and Effects as Polymer Reinforcing Agents. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013, 5, 2999-3009.

-

- 34. Uşurelu, C. D.; Panaitescu, D. M.; Oprică, G. M.; Nicolae, C.; Gabor, A. R.; Damian, C. M.; Ianchiş, R.; Teodorescu, M.; Frone, A. N. Effect of Medium-Chain-Length Alkyl Silane Modified Nanocellulose in Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) Nanocomposites. Polymers 2024, 16, 3069.

-

- 35. Wang, Y.; Gao, M.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Feng, A.; Zhang, L. Recyclable, Self-Healable and Reshape Vitrified Poly-dimethylsiloxane Composite Filled with Renewable Cellulose Nanocrystal. Polymer 2022, 245, 124648.

-

- 36. Hou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, M.; Yu, H. Y.; Wang, X. High Self-Extinguishing and Thermal Insulating PA66 Composites Enhanced with Flame-Retardant Cellulose Nanocrystals. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 142129.

-

- 37. Mekonnen, T. H.; Haile, T.; Ly, M. Hydrophobic Functionalization of Cellulose Nanocrystals for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance of Polyurethane Nanocomposite Coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 540, 148299.

-

- 38. Khanjanzadeh, H.; Behrooz, R.; Bahramifar, N.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Bacher, M.; Edler, M.; Griesser, T. Surface Chemical Functionalization of Cellulose Nanocrystals by 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 1288-1296.

-

- 39. Maria Chong, A. S.; Zhao, X. S. Functionalization of SBA-15 with APTES and Characterization of Functionalized Materials. J. Phys. Chem. B.2003, 107, 12650-12657.

-

- 40. Liu, Z.; Duan, X.; Qian, G.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, W. Eco-friendly One-pot Synthesis of Highly Dispersible Functionalized Graphene Nanosheets with Free Amino Groups. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 045609.

-

- 41. Mayorga-Garay, M.; Cortazar-Martinez, O.; Torres-Ochoa, J. A.; Silvas-Cabrales, D. P.; Corona-Davila, F.; Guzman-Bucio, D. M.; Carmona-Carmona, J. A.; Herrera-Gomez, A. XPS Study of the Nitridation of Hafnia on Silicon. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 678, 161073.

-

- 42. Larraza, I.; Vadillo, J.; Santamaria-Echart, A.; Tejado, A.; Azpeitia, M.; Vesga, E.; Orue, A.; Saralegi, A.; Arbelaiz, A.; Eceiza, A. The Effect of the Carboxylation Degree on Cellulose Nanofibers and Waterborne Polyurethane/Cellulose Nanofiber Nanocomposites Properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 173, 109084.

-

- 43. Barick, A. K.; Tripathy, D. K. Effect on Nanofiber Material Properties of Vapor-Grown Carbon Nanofiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU/CNF) Nanocomposites Prepared by Melt Compounding. Composites Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2010, 41, 1471-1482.

-

- 44. Prataviera, R.; Pollet, E.; Bretas, R. E. S.; Avérous, L.; de Almeida Lucas, A. Melt Processing of Nanocomposites of Cellulose Nanocrystals with Biobased Thermoplastic Polyurethane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci.2021, 138, 50343.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2026; 50(1): 93-99

Published online Jan 25, 2026

- 10.7317/pk.2026.50.1.93

- Received on Jul 3, 2025

- Revised on Oct 13, 2025

- Accepted on Oct 17, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- PilHo Huh** , and Seong Il Yoo

-

Department of Polymer Engineering, Pukyong National University, Busan 48513, Korea

**Department of Polymer Science and Engineering, Pusan National University, Busan 46241, Korea. - E-mail: pilho.huh@pusan.ac.kr, siyoo@pukyong.ac.kr

- ORCID:

0000-0001-9484-8798, 0000-0002-6129-6824

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.